Commissioner Dyson Heydon’s 79 recommendations from the Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance represent a steamroller approach to industrial democracy and basic human rights, such as the right to collectively bargain and the freedom of association.

Heydon referred 45 instances of possible corruption for further investigation and in a novel move for Royal Commissions, released details of “possible” offences by a number of senior unionists (mostly procedural or quasi-criminal in nature) after making his findings on the basis of pared-back rules of evidence.

If these recommendations become law, union-busting in the 21st century will resemble a dim likeness of the Combination Acts from early 19th century Britain. Like that legislation, these recommendations propose subjecting unions and officials to criminal as well as increased quasi-criminal sanctions.

Criminal offences will be further be subject to the lowest criminal standard of proof (“recklessness”) while the existing civil standard for quasi-criminal offences is also to be lowered. The offence provisions echo the “good faith” provisions under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), which create a murky and highly discretionary charge.

Furthermore, if the recommendations are taken up by the Turnbull government, the State will be vested with increased powers to completely dismantle or “deregister” recalcitrant trade unions through a new Registered Organisations Commission.

In a contemporary twist to these old laws, the Royal Commission has recommended increased surveillance, monitoring and prosecution by a specialist union-busting police force as well as the compulsory professionalisation of working-class trade unions, by imposing strict character and educational requirements on union officials.

Infringements of certain procedural industrial laws – such as the payment of union dues, rights of entry, secondary boycotts and prohibited industrial action – will result in increased criminal and quasi-criminal penalties.

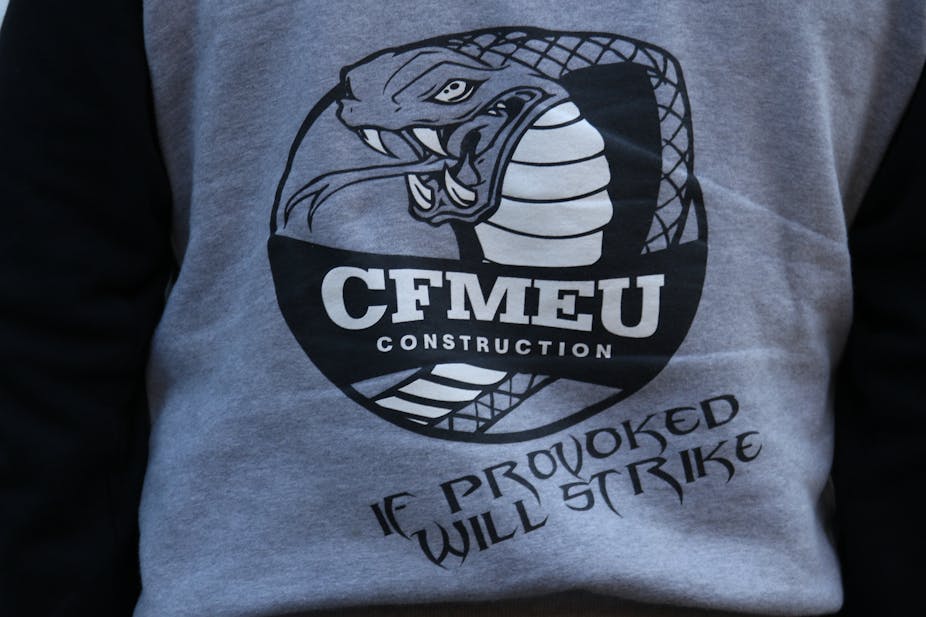

Senior officials will face criminal liability for infringements by stewards on the shop floor, followed by deregistration of the union for repeated or serious breaches. Even picketing will be considered an offence, rendered of the same criminal status as an unsolicited strike.

The Royal Commission and the Liberal Party are calling for corporate-style regulation of unions on the basis of tit-for-tat political argument. This is a position that neglects to acknowledge that corporations exist exclusively to advance the profits of shareholders, while trade unions are community organisations that collectively advance the interests of members, to address a fundamental inequality in the bargaining power between individual workers and capital.

Given that corporations and unions perform fundamentally different social roles, they should accordingly be treated differently by law. This much is acknowledged by both Australian and international expertise on the regulation of trade unions to defeat corruption.

Detailed Australian research demonstrates that corrupt practices within unions are best defeated from within unions, rather than subjecting unions to criminalisation and oppressive regulation by the state.

This research reveals that only strong unions tend to defeat corruption. Strong unions are those that are able to foster internal cultures of democracy through networks of membership participation and communication, as free as possible from interference by a hostile media and political arena.

Indeed, the historical experience of union-busting in the United States provides clear evidence that regulation leads to weakness, desperation and further corruption within unions.

Almost every comparable advanced economy to Australia (including Britain, Sweden, Denmark and Germany) maintains strong codes of corporate regulation. Unions are not regulated by the State, and in many cases are protected by constitutional rights to collectively bargain, as well as the freedom of association (for instance the United States).

The Japanese Constitution specifically enshrines the right to form labour unions to advance the rights and interests of workers. In countries such as France, where limited regulation exists in respect to discrete issues like internal trade union elections, unions are provided a statutory and institutional role in the governance of the state.

In Australia, not only do unions lack any constitutional legal protection, they have suffered vigorous and sustained attack by Coalition federal governments since 1996. In 2007 these policies cost the Coalition an election.

The Coalition now has a choice to preserve industrial democracy and secure an easy electoral victory, or to continue the war on unions and lose their middle ground for the foreseeable future.