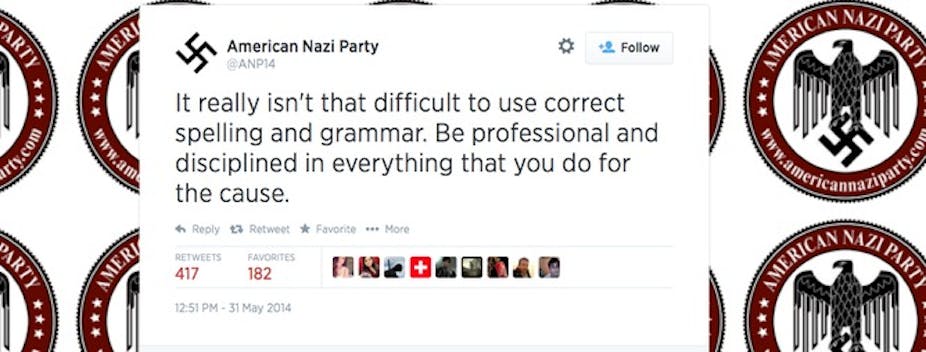

You have to look long and hard to find a joke with “grammar” in the punchline. But recently, a very funny grammar joke turned up on Twitter, thanks to the American Nazi Party, which feels bound to maintain extremely high standards in purveying ultra-racist views and in the use of “correct grammar”.

One tweeter quipped:

We have reached peak grammar Nazi.

Sadly, that’s unlikely. Twitter is rife with self-confessed grammar nazis. Over 80 tweeters use “grammar nazi” in their handle or display name. And cut from the same cloth are tweeters who call themselves “grammar police”, “grammar fascist”, “grammar evangelist” and “grammar bitch”.

Some of these grammar tweeters have thousands of followers. @GrammarGirl has well over 240,000.

The great crime of grammar nazis is that they perpetuate a simplistic view of grammar. They treat grammar as if it were just a set of rules to be followed. It’s not.

I say this as someone who not only teaches grammar, but gives my students grammar assignments and grammar exams. Last year, a young bright student told me, in week three of my undergraduate grammar course, that he was “terrified”. This was not because I was channelling the Führer. I’m definitely no grammar nazi.

But I’m not a grammar anarchist either. Grammar is not a free-for-all. It has structure and organisation.

An interplay of grammar and ideology

Unlike the simplistic view of the grammar nazi, the structure in language is not only intricate and multilayered, but contingent. In other words, with few exceptions, the grammar of a word depends on what else is around it.

Verbs can be nouns, and nouns can be verbs – which means even these “basic categories” of grammar are, well, neither basic nor categorical. Like genes, grammar is responsive to the environment.

All this makes sense when you think about its evolution. Language, like all forms of human culture, is the outcome of hundreds of thousands of years of humans going about their daily lives. In dialogue with each other and the natural world, humans have built complex, subterreanean, meaningful grammatical systems.

When you really study it, grammar turns out to be profoundly connected to human preoccupations. The grammars that humans have built, collectively and largely unconsciously, give us back our models of stasis and flux, of what we can and can’t quantify, of causation or its absence, of time and uncertainty and much much more.

Grammar is not only about making sense of our world experience. It is also deeply interpersonal. Grammatical distinctions allow us to be dialogic, and to construe the many discriminations we make in our social structures. It allows us to argue, to flatter, to persuade, to defer, to cajol, to demonise, to proselytise.

The evolution of language helped along the evolution of our complex brains. It enabled us to move out of what neuroscientist Gerald Edelman called “primary consciousness” or “the tyranny of the extended present”, into a distinctly human higher-order consciousness.

Rather than tips for dotting i’s and crossing t’s, grammar is a metaphysics for living. In the words of the linguist M.A.K. Halliday, grammar is an “ideological interpretant” built into language.

This conception of grammar – to which many linguistics and other scholars have contributed – owes nothing to Hitler or Proudhon. If anything, it is beholden to Karl Marx. Why? Because grammar emerged through the dialectic of individual social action and collective history. For the “grammar Marxist”, the experience of living explains both the evolution and the essence of grammar.

Students front up to my grammar classes, after 13 long years of school, knowing essentially nothing about the subterranean grammatical systems that power human interactions. While my colleagues in mathematics are teaching advanced algebra and calculus to their undergrads, I have to start from scratch, right back to nouns and verbs.

Hands up anyone out there who thinks a verb is “a doing word”? Sure, verbs do construe processes of action. But this is a tiny part of its work.

Not only do verbs also allow us to construct abstract relations (a big thanks here to the verbs be and have who make this possible), but, mapped onto a choice of lexical verb, we find a host of other grammatical options. These include verb tense (primary and secondary), finiteness, modality, polarity, conation, causatives and voice.

Defying simplistic rules

Have I lost you? Yeah, well, grammar is complex. That’s a message lost entirely on grammar nazis, not to mention those producing and promoting the NAPLAN “language conventions” tests.

Some linguists make their lives easy, by studying invented, decontextualised sentences. My students study grammar in all its empirical glory – in news reporting, political speeches and interviews, advertising, science textbooks and literature. For their assignments this semester, my students looked at grammatical patterning in an OXFAM brochure, a speech by Nova Peris on proposed changes to the Racial Discrimination Act, and a translation of a Checkov short story.

Research in Sydney primary schools in the 1990s, by Professor Geoff Williams of the University of Sydney, showed that kids are capable of learning these complex ideas about grammar. More importantly, the research showed that understanding these concepts makes kids better, more reflective, users and analysers of language.

But so long as, in the popular imagination, the grammarian continues to be like a traffic warden, writing out tickets for parking infringements, the organic beauty, complexity and diversity of grammar will remain obscured.