Welcome to Hot Seats, a series in which local academics report from the UK’s marginal constituencies. In this instalment, Charles Pattie takes the measure of Nick Clegg’s battle to retain Sheffield Hallam.

Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg faces two battles in Britain’s general election. The first, obviously, is for his party’s standing in the country – but his second battle is closer to home, in his Sheffield Hallam constituency, where he is fighting for his political life.

At the start of April, Lord Ashcroft gave the Liberal Democrats a serious scare with his latest poll of the seat, which put Clegg on 34% – two points behind Labour. If these numbers are borne out on May 7, Clegg could be his party’s highest-profile casualty in what looks set to be its worst general election since it was formed.

That Clegg is at risk of losing his seat at all is remarkable, since this is just not something that happens to the leaders of mainstream political parties. Modern party leaders tend to have one basic thing in common: they are generally MPs for seats where their party wins by comfortable majorities. Members with precarious majorities simply cannot guarantee being in the Commons long enough to rise through the ranks.

Since 1945 (and excluding Northern Ireland), leaders of parties with Westminster MPs have lost their seats on only five occasions. Three were leaders of nationalist parties: the SNP’s Gordon Wilson lost Dundee East in 1987, and Plaid Cymru’s Gwynfor Evans lost Carmarthen in both 1970 and 1979.

The other two defeated leaders both fell in the 1945 election, when the Liberals’ Archibald Sinclair lost Caithness and Sutherland and Liberal National leader Ernest Brown was defeated in Edinburgh Leith. No leader of a party with more than a handful of MPs has lost their seat since then.

So how likely is it that Clegg will join the small roster of party leaders ousted by the voters?

Ominous trend

At the 2010 election, he won 53.4% of the vote in Sheffield Hallam, substantially increasing his majority over the Conservative (who got 23.5%) to a very healthy 15,284. Labour, meanwhile, came in a distant third, with just 16% of the vote. Clegg’s 30-point margin made Sheffield Hallam one of the safest constituencies in the country.

Of course, 2015 is going to be a brutal election for the Liberal Democrats, whose national standing has slipped severely since joining the coalition. But if we apply the trends since 2010 implied by current national polls to Sheffield, Clegg’s majority then should still see him through to victory on May 7, albeit with a much reduced majority.

A simple approach is to apply the national percentage point changes to each party’s vote share suggested by the national polls to the 2010 result in Hallam.

Liberal Democrat support nationally has dipped from 23% in 2010 to 8% in current polls, a fall of 15 percentage points. Applying that to Clegg’s 2010 vote share of 53% in Hallam would bring his vote down to 38% in May – embarrassing, but still enough to win the seat if the other parties’ returns also move in line with national trends.

What’s more, incumbent MPs tend to gain something of a personal vote, built on recognition, community service and so on. This tends to insulate them somewhat from more general falls in their party’s standing. Liberal Democrat MPs have tended to be particularly good at building personal bases in their constituencies, and the party has a reputation for highly effective constituency campaigning.

All parties gain to some extent from their constituency campaigns, but the Liberal Democrats are a formidable force when it comes to doorstep electioneering. The Sheffield Hallam Lib Dems are no exception, and are currently campaigning very hard indeed on behalf of their candidate and leader.

Yet things might actually be worse for the Liberal Democrats in Hallam than the national polls suggest.

Swinging away

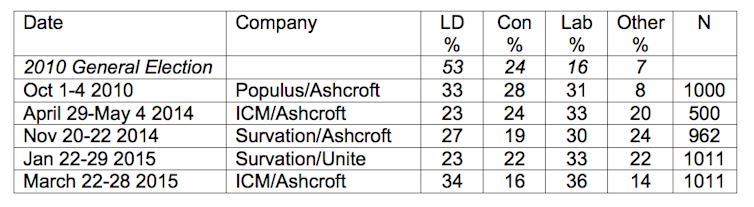

Since the 2010 election, at least five publicly available opinion polls, have been conducted in the constituency. None makes good reading for the Liberal Democrats: support for the party locally has dropped steeply, and Labour has been the main net beneficiary.

At the very least, these polls suggests Clegg has a serious fight on his hands to hold his seat. And if these constituency polls prove correct, his parliamentary career could soon be over, at least in the short term.

But again, this demands some context. These polls suggest a quite remarkable swing away from the Liberal Democrats in Hallam, much larger than the national swing away from the party. What is more, they point to a Labour victory there, which would be a first.

Labour has never won Sheffield Hallam, or come remotely close. The constituency is one of the most affluent in the country and for most of the 20th century, it was held by the Conservatives. The Liberal Democrats took the seat in 1997 and have retained it ever since, with Labour squeezed into a weak third place.

The problem for Clegg is that this almost certainly depended on tactical voting, which was a major factor in the Liberal Democrats’ original 1997 victory in Hallam. Many Labour supporters in the seat were keen to unseat the Conservatives locally but, knowing their candidate had no realistic chance of winning there, they swung behind the Liberal Democrats. So while the 1997 election was a Labour triumph nationally, Labour’s vote share in Hallam actually dropped from 20% (within the 1992 boundaries) to 13%.

This tactical balance has kept the Lib Dem majority up ever since – but now the party is governing with the Conservatives, the logic has collapsed. No-one voting to spite the Conservatives will support the deputy prime minister of a Tory-led government.

Campus politics

To make matters worse for Clegg, Hallam is an unusually university-centric constituency.

The seat has one of the highest proportions of university graduates of any constituency in Britain: at the 2011 Census, 44% of its adult population had a degree or equivalent qualification. Many employees at Sheffield’s two universities, especially academics, live in the constituency – including me. The east of the seat also encompasses the University of Sheffield’s main student village, housing scores of undergraduate students.

Before 2010, this would have been good news for a Liberal Democrat, since the party has always done particularly well among graduates. But thanks to the Conservative-Lib Dem measure to raise fees to £9000 per year, many erstwhile Liberal Democrat voters feel betrayed by the policy reversal, and students most of all.

And while young people in general tend to vote at lower rates than the population as a whole, the signs are that student turnout in 2015 will be high. Just how angry today’s undergraduates are about the new fee level may be a core determinant of Clegg’s personal election chances.

The election is taking place during term time, and the Sheffield University and Sheffield Hallam University Students Unions are running a joint campaign to ensure that as many students as possible register to vote. While most of those doing so will vote in the neighbouring Sheffield Central constituency, a significant minority will register in Hallam.

No-one can be sure how many will take the opportunity to express their view on their fees.

Hands off

None of this means Nick Clegg is guaranteed to lose his seat. The Liberal Democrats’ constituency campaign is already in full election mode, and its staffers and activists are fully aware of the polls’ dire predictions.

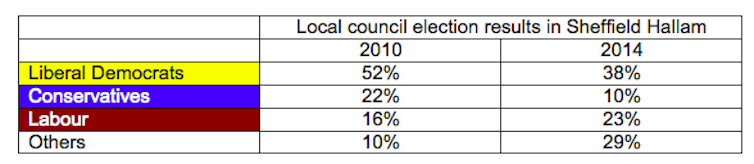

Local council election results in the wards making up Hallam constituency, while by no means good for the Liberal Democrats, paint a more equivocal picture than the polls, as a comparison of the 2010 local election results with those in the most recent local elections in 2014 shows.

These numbers are not great – but if played out on May 7, they would be enough to re-elect Clegg.

But the Hallam Lib Dems would be foolish to draw too much hope from their local election performance, since the Conservatives fielded no candidate in two wards in 2014, artificially reducing their vote and probably increasing Lib Dem support.

It’s also possible that local Conservative supporters could back Nick Clegg to stop Hallam going Labour for the first time. If Conservatives shift to the Lib Dems in sufficient numbers, that might compensate sufficiently for the loss of Labour tactical voters for the Lib Dems and Clegg to hold Hallam.

On the ground, there are signs that the Conservatives are not going out of their way to discourage this sort of thing. On my desk, I have five pieces of election literature which have been delivered by the local Labour campaign over the last week or so, six Lib Dem leaflets, one leaflet from an independent candidate … and nothing whatsoever from the local Conservatives.

The same goes for posters in windows and signs in front gardens: a smattering of Labour and Liberal Democrat banners, but little sign of a Conservative campaign at all.

It may be that the Tories are keeping their powder dry until the final weeks of the campaign. But they may have another strategy: to avoid splitting the anti-Labour vote by making only the most token effort in the seat.

Watch this space

Sheffield Hallam will undoubtedly be one of the biggest battles to watch on election night. Some pundits are already calling the seat as a Lib Dem hold or loss.

Political commentator Ian Dale, for instance, thinks the seat is a “dead cert Lib Dem hold,” whereas an Ashcroft poll led the newspapers recently pouring cold water on that prediction.

If pushed, I also suspect Clegg will win here, albeit with a much reduced majority.

But I could be wrong: what with those polls, the student vote, a remarkably confident and visible Labour campaign in a seat where the party has never performed well, and palpable nerves among local Lib Dems, nothing is certain. There are enough straws in the wind that we could still be about to witness one of the rarest events in British politics: the defenestration of a major party leader.