Ambitious and mercurial, with a dark past, former army general Prabowo Subianto has spent a lifetime vying for the ultimate prize in Indonesian politics. Now, with a large lead in the latest polls ahead of this week’s election, it looks as though the presidency is finally within his grasp.

So, who is Prabowo and how will he change Indonesia if he wins?

A rapid rise through the military ranks – and fall

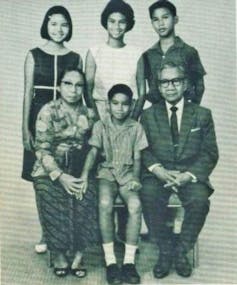

Prabowo Subianto Djojohadikusumo is a true Indonesian blueblood. His family claims to be descended from national hero Diponegoro, a prince of the Mataram sultanate who led the Java War rebellion against Dutch colonial forces in the 19th century.

Prabowo’s grandfather was the founder of Indonesia’s first state bank and a prominent member of Indonesia’s independence movement. His father was a leading economist who served as minister of finance, minister of trade and minister for research in the government. His brother is a wealthy tycoon.

Prabowo, too, has long sought national prominence. An ambitious military officer serving mostly in the Special Forces (Kopassus), his marriage to a daughter of the authoritarian former president, Soeharto, fast-tracked his career. Prabowo rose to the rank of lieutenant general and, finally, the key position of commander of the powerful Army Strategic Reserve (Kostrad) in the capital, Jakarta.

As Soeharto’s regime began to falter amid the financial crisis of 1997, Prabowo become involved in covert operations to defend Soeharto’s army-backed and repressive New Order regime against its critics.

Read more: Soeharto: the giant of modern Indonesia who left a legacy of violence and corruption

Under his leadership, the Special Forces’ “Rose Brigade” was accused of abducting and torturing more than 20 student protesters, 13 of whom are still missing, presumed dead. Prabowo has admitted to the abductions, but denies being involved in any killings.

Prabowo never faced trial, although several of his men were tried and convicted. The allegations against him meant he was, for years, denied a visa to enter the US.

Prabowo also denies a wide range of earlier accusations relating to human rights abuses committed by Special Forces under his command in East Timor and Papua, including alleged torture and killings.

He also denies accusations he was involved in engineering the violent rioting in the capital in 1998 that contributed to the collapse of his father-in-law’s regime, likely the result of an internal military struggle to become Soeharto’s successor. It seems Prabowo hoped to climb high amid the chaos at the time.

After Soeharto resigned in May 1998, his newly installed successor, B.J. Habibie, refused Prabowo’s request to be made head of the army, instead effectively demoting him. Prabowo is said to have responded by arming himself with a pistol and driving to the palace with truckloads of soldiers, but was stopped outside the president’s office.

Soon after, Prabowo was cashiered for “misinterpreting orders”, although the precise details of his dismissal still remain mysterious. He went into voluntary exile in Jordan for some years and it seemed his career was over.

Three unsuccessful bids for higher office

But Prabowo remained an ambitious man. By 2009, he was a wealthy business figure and had co-founded his own political party, Gerindra. He had also rehabilitated himself enough to make a formal bid for power, running for vice president in the 2009 elections on a ticket with former president Megawati Soekarnoputri. They lost in a landslide.

In 2014, Prabowo tried again. This time he ran as a presidential candidate against Joko “Jokowi” Widodo. Prabowo campaigned as a nationalist “strongman”, riding his horse around stadiums of cheering uniformed supporters and promising a return to the authoritarian model of the New Order. He lost both the election and a challenge to the results in the Constitutional Court.

In 2019, he tried once again against Jokowi, this time turning to conservative Islamists to support him. He was a strange choice as their figurehead, given he had a Christian mother and brother and, although a Muslim himself, had previously shown little public piety. In his 2014 campaign, he had even promised to protect religious minorities against Islamists.

Prabowo’s use of identity politics proved deeply polarising, strengthening the hand of hardline Islamist groups in Indonesia and deepening tensions between religious communities for years to come.

But Prabowo lost this election, too. He accused Jokowi of cheating, sparking rioting in Jakarta in which eight people died. He again contested the results in a highly publicised Constitutional Court challenge, which he also lost.

Prabowo then made the extraordinary decision to reinvent himself again. Dumping his supporters, he took the position of defence minister in the cabinet of his rival, Jokowi. The two former foes were photographed shaking hands and sharing jokes to seal their extraordinary deal.

For the next four years, Prabowo dutifully performed the role of loyal minister – even when Jokowi’s government moved against some of the Islamist organisations that had backed him in his last bid for the top job.

Controversial political moves

Now 72, Prabowo’s ambitions are undiminished, but his tactics have, once again, changed dramatically.

In his current run for president, Prabowo has selected Jokowi’s son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, as his vice-presidential running mate. And Jokowi himself now backs him. (Although Jokowi has never explicitly endorsed Prabowo, Gibran’s candidacy makes Jokowi’s preferences crystal clear.)

Jokowi’s decision to join forces with Prabowo and his Gerindra party was driven by the fact he was prevented from running himself by the two-term presidential limit in the constitution. He therefore needed to find another way to maintain influence. Having his son as vice president would certainly suffice.

Jokowi is hugely popular, with approval rates still well over 70%. This means his decision to back Prabowo may – at last – deliver the presidency to the former general.

But building a new alliance with Prabowo has proved to be a seismic event in Indonesian politics, for two reasons.

First, according to the country’s election law, candidates for president and vice president must be at least 40 years old. The 36-year-old Gibran didn’t qualify.

Helpfully, the chief justice of the Constitutional Court was Gibran’s uncle and had been appointed by Jokowi. The court duly delivered a ruling that younger candidates could run if they had held elected office as a regional head. Gibran just happens to be mayor of the city of Solo (a position his father once held), so he was now eligible.

Uproar ensued, and the chief justice was demoted for his obvious conflict of interest. But, incredibly, the decision stood, and Gibran is running.

Second, Jokowi is a member of the PDI-P party, which had twice nominated him for president. The party has its own candidate running for president, Ganjar Pranowo.

So, by backing Prabowo, Jokowi has effectively turned his back on his own party and may help defeat its candidate for the presidency.

His actions also pose a major threat to PDI-P’s prospects in the legislative elections (held at the same time as the presidential vote). To the PDI-P leader, former president Megawati, and many of her supporters, Jokowi is now a traitor and enemy who may inflict huge damage on their political prospects.

Why this election matters

Prabowo’s big lead in the polls is partly thanks to Jokowi’s support and the many government officials now openly backing him. However, Prabowo has undergone (yet another) spectacular reinvention in recent months that has helped as well.

His campaign team has heavily promoted him as a baby-faced gemoy (cute) grandpa, using viral memes, video clips and even huge screens with anime avatars of Prabowo and Gibran smiling and winking at passers-by.

But Prabowo is not cute. In fact, he has repeatedly said Indonesia’s democratic system is not working and the country should return to its original 1945 constitution. This would mean unravelling most of the reforms introduced since Soeharto fell, which are largely based on constitutional amendments.

Among other things, Indonesia’s charter of human rights would go, as would the Constitutional Court. The courts would no longer be independent, direct presidential elections would end, the two-term presidential limit would go and the president could again control the legislature.

Of course, these changes might not be easily done, but it is a chilling prospect if Prabowo wins. And that may happen because much of the electorate doesn’t seem to care all that much about the consequences of picking him.

The average age of Indonesia’s 205 million eligible voters voters is just 30, and more than half are millennials or Gen Z. This means many have no memory of Soeharto’s oppressive and abusive New Order that Prabowo seems to want to revive.

Young voters also seem untroubled by Prabowo’s dark past and the credible allegations of violence and human rights abuses made against him. Instead, they seem captivated by the cute Prabowo and cool Gibran imagery saturating social media, backed by the charisma of Indonesia’s most popular public figure, Jokowi.

If Prabowo does become president, as many now expect, Indonesia’s fragile democratic system may be the next thing he reinvents – or, more likely, dismantles.