Myanmar makes many headlines these days. While most of the focus has been on the Rohingya issue, the country is also heading towards an important economic and livelihood crisis. Myanmar was once called “Asia’s rice bowl”, and that label stuck for much of the 20th century. While the country is keen to reclaim this title, it’s doubtful this ambition will be realised soon.

At the centre of this looming livelihood crisis is large dams. In September 2011, now six years ago, Myanmar’s then-president Thein Sein surprised his countryfolk and international observers by suspending the construction of the Myitsone Dam project in northern Myanmar, the largest of seven dam projects to be built on the Irrawaddy River.

The project had, from its commencement in 2009, been extremely unpopular in the country because of its vast negative impacts on livelihoods, disrupting fisheries and local agriculture.

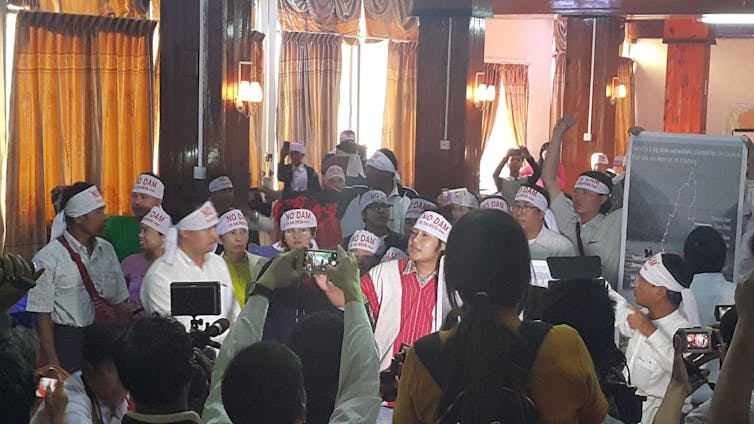

Even though Myanmar’s political system was extremely restrictive at this time, a major campaign had emerged against it, led by local communities and NGOs.

The Myitsone Dam’s suspension is widely considered as the main symbol of Myanmar’s political change from autocracy to democracy.

When I carried out field research in Myanmar last year a Burmese environmental activist told me:

This was the first time since the 1962 Burmese coup d'état that the country’s political leadership took public opinion into account

Originally, the Myitsone Dam project was supposed to be completed this year. Although a decision on its fate was supposed to be made last year by Myanmar’s leader Aung San Suu Kyi, it remains suspended until today. Many fear, though, that construction may resume soon. The impacts on livelihoods would be devastating.

Myanmar Damocles projects

The main purpose of the dams to be built on the Irrawaddy River is hydropower production. Myanmar’s hydropower potential stands at 108 GW – the largest potential of any country in Southeast Asia. But only 52% of households have access to electricity.

The country needs to harness its vast hydropower resources to change this, particularly since Myanmar’s renewable energy potential beyond hydropower is relatively limited. For instance, Myanmar has 3,400 km2 of land with wind speeds greater than six meters per second, the minimum needed for modern wind turbines. This equates to only 0.5% of the country’s total area. Hence, wind power will not be able to satisfy Myanmar’s rapidly growing energy needs. Myanmar is developing renewable alternatives to generate energy as it has only modest fossil fuel potential.

The planned projects on the Irrawaddy River have a combined capacity of more than 15 GW. For those to be resettled by them, they are so-called “Damocles projects”. This term reflects the constant threat hanging over villagers in the communities which are close to the dams: the fear of resettlement. Many of the (to be displaced) communities are Kachin, a Christian minority in Myanmar that has lived on these lands for hundreds of years already.

Such projects create tangible negative impacts on communities even if not implemented. For instance, communities invest much less in homes and businesses due to a fear of being resettled soon, while stress levels for resettlees are particularly high. Advocacy work against a dam project can also heavily consume people’s time and resources.

But the projects’ social impacts exceed far beyond resettlees. Almost 40 million people live in the Irrawaddy River Basin. This equates to two-thirds of Myanmar’s total population.

Many of these rely on fisheries for sustenance and/or a large part of their food. However, large dams act as barriers in a river system, blocking the movement of migratory fish species. So migratory fish downstream can be reduced by as much as 20% due to large dam construction, according to some estimates, while measures to address dams’ negative impacts on fisheries such as fish ladders can only partially mitigate this effect.

Many point out that large dams boost agricultural productivity which can offset the negative impacts on fisheries. Indeed, flooding can be regulated via dams which can improve agricultural productivity by several percentage points, according to some studies.

However, large dams can also block the flow of nutrients which, in turn, can reduce agricultural yield. Myanmar still is a predominantly agricultural economy, with around two-thirds of the population employed in agriculture and almost 40% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) generated in the agricultural sector. Reduced agricultural productivity would thus be devastating for the country.

Conflict zones

Myanmar’s best potential hydropower sites are all in conflict areas.

Ethnic conflict between the Kachin in northern Myanmar and the Burmese military -with the Kachin demanding more self-determination from the national government since the early 1960 already - was reportedly exacerbated in 2010 once work on the Myitsone Dam had started.

The Kachin and the Burmese military then clashed in 2011 ending a 17-year ceasefire agreement. Some international observers have attributed this to the Myitsone Dam construction.

Such conflicts can further threaten food security since they displace thousands of people who then struggle to rebuild their livelihoods. While international attention is focused on Myanmar’s evolving Rakhine state crisis with the Rohingya, a less noticed military conflict is also waging in northern Kachin state.

Air strikes by the Burmese government have gradually intensified since 2016 because the Burmese government wants to eliminate the Kachin resistance in an effort to unite Myanmar. Kachin State has not witnessed such a violent armed combat for at least 20 years. Any dam constructed in Kachin State these days – which would be an initiative led by the national government – would further fuel this conflict. It’s been estimated this ongoing conflict has led to the displacement of 100,000 civilians.

Impacts of dams

Large dams will have profound impacts on livelihoods of those living in the Irrawaddy River Basin.

Hence, harnessing Myanmar’s hydropower resources will require careful managing of trade-offs by policy-makers – which includes thorough assessments of likely impacts and the creation of alternative livelihoods for those negatively affected by large dams. Myanmar has many regulations in place already – most notably its Environmental Impact Assessment Procedures, adopted in early 2016 – to deal with these trade-offs.

These are (largely) sound on paper. However, few of them are implemented and until today little information is shared by the government regarding dam development in Myanmar. If the country’s political leadership wants to achieve sustainable development for Myanmar, this will need to change immediately.