A few weeks ago, I wrote for The Conversation to try to explain why so many men get away with rape. It is now clear that one of those men was a London police officer, PC David Carrick.

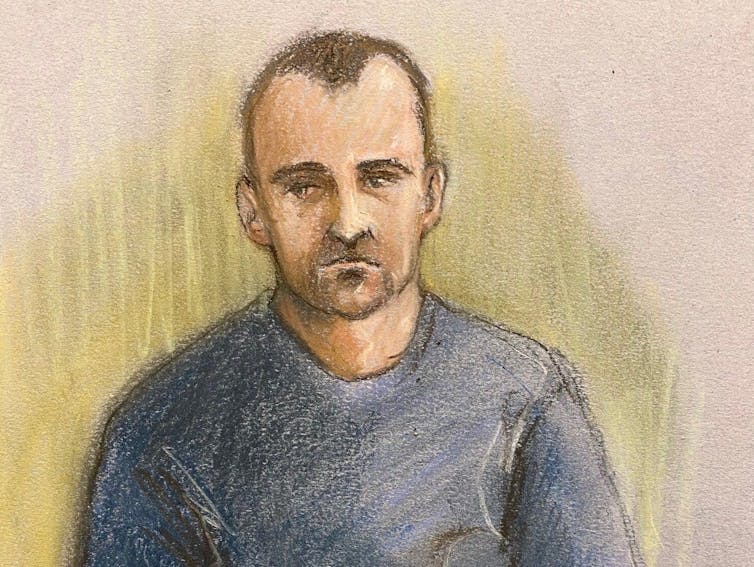

Carrick has admitted to more than 40 offences of rape and false imprisonment committed against a dozen women over the past 20 years, and has now been dismissed as a police officer.

Like Wayne Couzens, the former PC who murdered Sarah Everard, Carrick was selected through a recruitment procedure meant to weed out any “bad apples” before they could poison the barrel. Both were supposedly vetted and psychologically assessed to enable them to carry deadly firearms.

There were plenty of prior indications that Carrick and Couzens were dangerous men, patently unfit to be police officers. Your mates don’t nickname you “bastard Dave” (as boasted by Carrick) or “the rapist” (Couzens) for nothing. Yet their notoriety among colleagues did not seem to warrant the attention of the Met professional standards directorate, whose job it is to monitor and improve the health of the organisation in terms of integrity and corruption.

The first line of defence against criminals like Carrick and Couzens being able to join a police force is initial recruitment vetting. There are three levels of vetting for police officers, the most advanced only being required for very senior officers or counter-terrorism posts.

For most regular officers, the only vetting takes place when they are recruited. It mainly relies on the applicant filling in an extensive form, giving details about family members, financial affairs, criminal convictions, previous addresses and employment history. The force recruiting department then checks various databases for any criminal convictions or police intelligence entries (such as arrests or allegations where no action was taken). Having minor convictions will not necessarily bar someone from becoming a police officer.

Following Carrick, the Home Office has now instructed police forces to check their existing staff against these national databases.

The vetting process is rather passive – much reliance is placed on self-declaration, rather than proactive work to establish how an individual acts and thinks in their private life. There is no deep background check, no interviewing friends, colleagues and family, no visiting the applicant at home, or conducting an invasive social media screen.

Once an applicant has been accepted into the police, it is entirely possible that they could continue for their whole service (perhaps 35 years) with no further vetting.

Some forces require mandatory updates every ten years or when the officer moves to a different post. Carrick reportedly went through further vetting to become a firearms officer, and it is likely this would focus mainly on psychological profiling. Knowing now that he was in fact a violent sexual predator suggests there are limitations to this extra vetting.

Monitoring bad behaviour

In each of the UK’s 45 police forces, a professional standards department (PSD) is the front line against breaches of integrity that fall short of criminal behaviour. They should maintain an intelligence database which includes details of every complaint or allegation of misconduct made against officers and other police staff. The Met police are now investigating 1,000 sexual and domestic abuse claims involving its officers. The force PSD will examine these for evidence to dismiss officers for gross misconduct in proven cases.

Since a 1999 report on police integrity, PSDs have been urged to conduct robust investigations into allegations of officer misconduct. This is the case even if the evidence falls short of being able to charge an officer with a crime (such as a rape victim withdrawing their statement).

And, since 2004, the independent police oversight body in England and Wales, the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC), has had investigatory powers under the law. The IOPC (and similar bodies in Scotland and Northern Ireland) investigates the most serious allegations against police officers, providing it becomes aware of the case. The Charing Cross scandal – where officers used misogynistic slurs, rape jokes, insults and racist comments in a WhatsApp group – is an example of their work. The IOPC also maintains a confidential whistleblowing hotline for officers and staff to report concerns of misconduct or a criminal offence.

In the Carrick case, it appears that there was ample intelligence available to warrant a robust, proactive investigation by the force PSD into potential misconduct, even if women who initially complained of rape withdrew from the investigation. The IOPC is now reviewing why the Met failed to sack Carrick despite him being reported to police for sexual or domestic violence on no fewer than nine occasions. Their findings will hopefully tell us whether all possible steps were taken by the Met to thoroughly investigate this criminal.

Asked to comment on the PSD’s role in monitoring Carrick over the years, the Met pointed The Conversation to a public statement by Met Commissioner Mark Rowley. The commissioner said: “We failed as investigators where we should have been more intrusive and joined the dots on this repeated misogyny over a couple of decades.”

Getting rid of bad apples

Carrick was able to avoid a criminal conviction for years despite multiple allegations and complaints. But getting rid of a bad police officer does not require them to be convicted in court.

Officers in England and Wales are meant to uphold standards of professional behaviour, including honesty and integrity, not acting in discreditable conduct, and challenging and reporting improper behaviour by colleagues.

Carrick’s behaviour was clearly in breach of those first two standards. Arguably, his colleagues who suspected that he was bad may have been in breach of the third.

Officers who breach these standards could be subject to dismissal by a misconduct tribunal. Here, the standard of proof is held at the civil, rather than criminal, standard. That means the panel must decide “on the balance of probabilities it is more likely than not” that the officer is guilty of misconduct.

It is hard to understand why the Met PSD did not gather enough evidence to put Carrick before a misconduct tribunal. The force lead for professional standards, Assistant Commissioner Barbara Gray, accepts the police were deficient and missed investigative opportunities. A contrast perhaps with a smaller police force who, as soon as a whistleblowing officer alerted their PSD to colleagues making racist and homophobic comments, set up a complex covert investigation using listening devices to gather the necessary evidence to root out and dismiss those guilty of misconduct.

Part of the challenge may be the Met’s size. It is four times larger than any other UK police force and perhaps the deep-rooted culture of misogyny is just impossible for senior leaders to eradicate. It is time to seriously ask why the Met should not be broken up into a few manageable forces, mirroring every other English force in terms of size and governance structure.

The concept of “policing by consent” is what holds the whole system of police and public trust together. If the public loses faith in the integrity of officers, then they will not assist the police when it matters.