Last year I re-read Johnno, David Malouf’s 1975 novel, with a group of students. I was intrigued to find out how young men and women living in Brisbane today would relate to a novel that has cast such a long shadow over literary accounts of the city.

Week by week, I saw the novel draw the readers in, much as Malouf’s work often pulls us into the texture of an earlier Brisbane: the city brothels, the pubs, the River, the Botanical Gardens, the suburbs.

So it is a delight to see the exhibition David Malouf and Friends, showing at the Museum of Brisbane until November, celebrate Malouf’s contribution to Australian culture, in particular his role in capturing indelible images of Brisbane. It coincides with the author’s 80th birthday this year.

The exhibition’s paintings, poetry, sculptures, drawings and a fine large-scale installation explore the world that Malouf captures in prose. I was struck by how these works bring the viewer into the creative spaces that we so often find in Malouf’s writing – under the house, the veranda, the dusty corners of rooms – that are fertile ground for his imagination.

The writer gave us a picture of life in South Brisbane in his memoir 12 Edmonstone Street (1999). It is somewhat disconcerting to note that the address is now a commercial site.

But if you despair over the loss of Brisbane architectural heritage you can linger over the works in this exhibition: Brisbane-born painter Karla Marchesi’s large painting appropriately titled Thresholds (below) takes you back into the Brisbane of 12 Edmonstone Street, with layers of sub-tropical vegetation and glimpses through the dark undergrowth to timber palings and suggestions of a world beyond.

One of appealing features of David Malouf and Friends is a written response to each work from Malouf, that is presented adjacent to the work of each artist. He calls Marchesi’s paintings “lushly beautiful” and “perplexing” – which sounds about just right for a Malouf novel.

As a writer, Malouf plays on uncertainty and loss, the tricks of memory and place. Brisbane writer William Hatherell in The Third Metropolis: Imagining Brisbane Through Art and Literature, 1940-1970 (2008), argues that Malouf’s work presents two trajectories, the first being nostalgia, and the second a sense of unease that comes with visiting the past.

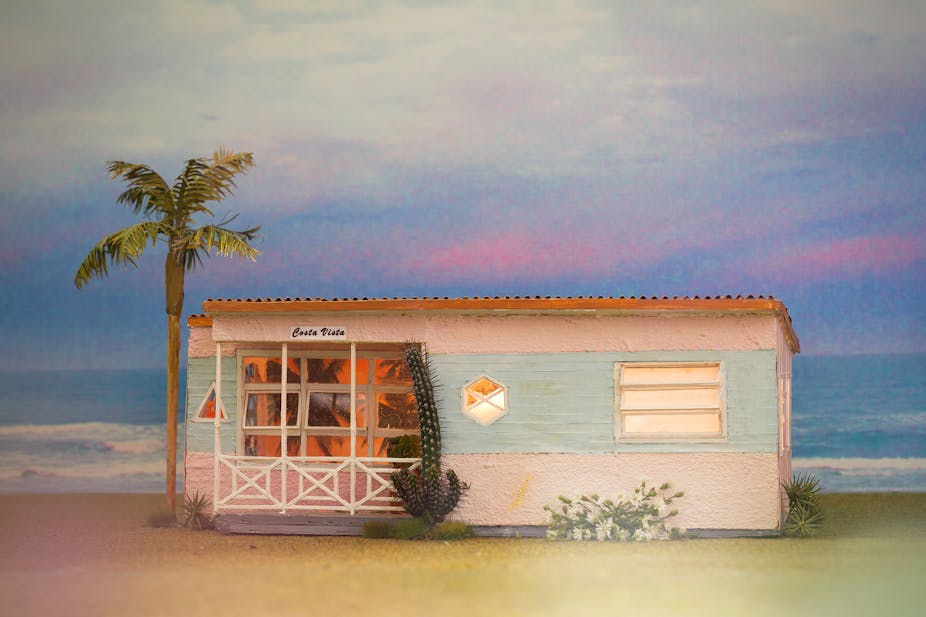

This sense of unease is palpable in several of the works on show. In Queensland artist Anna Carey’s re-working of the beach house Costa Vista (main image).

Brisbane-based artist Bruce Reynolds Bulimba Hydria (pictured), linoleum and paint on wood panel, offers a clever twist on a classical urn, made local by patches of linoleum. The linoleum references so many Queensland timber houses – the type of house on stilts depicted in Sydney-based artist Noel McKenna’s enamel on glass work The Condamine (below).

The exhibition is dominated, spatially at least, by Brisbane artist Camille Serisier’s Swan Song #7 (see below), a large scale work that the viewer can walk through. Here we find images of birds, light and water and a stage in which the visitor can enter and become a performer.

The work is a response to Malouf’s magical Fly Away Peter (1999) and the distinctive blue of a Brisbane sky forms a backdrop to the bird, boat and man who contemplate transformative moments.

French writer Michel de Certeau in The Practice of Everyday Life (1984) writes that as we go about our daily lives we inhabit a metaphorical city: one that is very different to the institutionally planned built environment. For de Certeau, as we move through our city spaces the legible order of the planners is displaced by the ambiguity of our own experience.

This sense of alternative histories and instability comes alive in Malouf’s Johnno and, as my student readers pointed out, it is a great novel to read when you are moving away from home, and away from Brisbane, as the author did when he left for Europe as a young man.

But, as Malouf told The Guardian recently:

I live in Brisbane in my head an awful lot of the time, and did for many years after I left.

Five Brisbane/ south-east Queensland writers have produced tributes to Malouf in the exhibition catalogue. Trent Dalton, Kristina Olsson, Nathan Shepherdson and Ellen van Neerven write of the impact of Malouf, on Australian writing, on Brisbane, and on their own creative work. The curatorial aim of providing contemporary responses, visual and written, to Malouf’s work has been fulfilled.

It is a nice turn of history for the exhibition to be held in the Museum, on the third floor of the Brisbane City Hall, overlooking the city streets, the river, the houses and the gardens, now inscribed with Malouf’s imagination.

David Malouf and Friends is at the Museum of Brisbane until November 23.