The introduction of the universal credit will change the face of benefit and welfare services for families all over the country. By making assumptions about digital literacy levels, the government is putting safety and security at risk.

The reformed benefits system, through which the different types of benefit currently provided by the state will be rolled into one single payment, is due to start taking effect in October, with the aim of moving the majority of benefits claimants to the new system by 2015-16. The policy is problematic not only because it takes responsibility away from the state and transfers it to the individual benefit claimant, but because it is based on a flawed understanding of digital literacy.

Central to the universal credit system is the shift from the idea of “digital when appropriate” to “digital by default”. The government is pushing for this approach after finding that 78% of existing claimants already use the internet and therefore concluding that the move to pay benefits directly into bank accounts is both feasible and logical.

In fact, as the academic literature will tell you, use is a far cry from literacy. Even young people have been shown to use the internet only in banal and routine ways, often encountering problems simply getting to grips with search engines. If the part of the population we most often assume to be technology-savvy is not using the internet to carry out complex tasks, it is worrying to think that benefits claimants of all ages are to be expected to carry out their financial dealings online and that they, not the government, will be accountable when things go wrong.

Reforming the benefits system will not make the digitally excluded suddenly digitally included, it will exacerbate the digital divide and turn it into a class divide, a geographical divide, an age divide and a gender divide.

Use of the internet for particular social relations and again bears little resemblance to the skills and knowledge needed for online banking. This poses security risks not only in case of phone theft, but also because apps that have not been endorsed by the Department for Work and Pensions are beginning to appear on the market. These include the Universal Credit Calculator, an app which asks for a range of information about you, your benefit claims, income and local authority area.

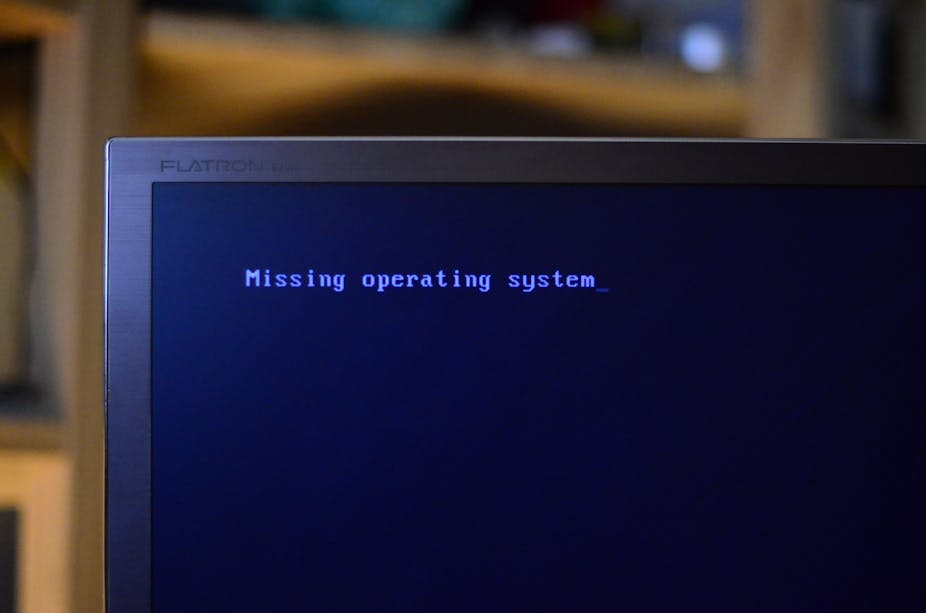

To have an online bank account requires sustained interaction online. Passwords and website addresses need to be remembered, access needs to be simple and secure. For the sections of the population most reliant on benefits, these are major barriers. Where will people access online banking if routers are not commonplace in homes, and public libraries are being closed down? How will they access e-banking if, as members of our local council in Leeds told us, many urban areas still have black spots where internet connection is not supported? Who will be responsible for the provision of routers after Universal Credit is enacted – the tenant or the landlord? And given that most people will see benefit payments stay the same, or decrease – how will routers, smart phones, laptops, PCs be paid for?

We may struggle to make a clear assessment of how big these problems are. The collapse of the entire spectrum of benefit payments into one single universal credit system means that benefits claimants from all backgrounds are bundled together into one big group. Removing the distinction between unemployment benefit and child credit, for example, places middle-class families who have technology at their fingertips alongside working-class families who don’t.

For most working mothers, the child tax credit will be part of the universal credit scheme. The government can use this switch to grouping benefits claimants all together to its advantage. Welfare reform minister David Freud has reasoned that because 75% of the employed population are already paid directly into their bank account, the move to paying benefits in the same way is but a “small change”.

Indeed, for the middle-class employed sectors of the population who will shortly find themselves claiming universal credit, the change will be small. For large parts of the population that claim benefits, it will be a much more significant step. But we will find it much harder to make the distinction. The heaping of all kinds of benefit claimants into one system has skewed the statistics – making those populations most affected seem more insignificant, making the numbers of digital literate seem larger, making the impacts of the changes seems smaller.

The universal credit system does not operate in a vacuum. It sits alongside welfare reforms, austerity measures and localism policies. From domestic and family relations, to the way an individual interacts with their neighbour, landlord, employer, job centre, or support worker: the lived realities of communities are changing forever. It is for these reasons, as well as the oversimplified claims about digital literacy upon which this reform is tenuously built, that the Communities and Culture Network+ is investigating the impact of these reforms on communities across the UK. We are working with local council, local community organisations and local communities themselves to first understand the full impact of these reforms, and second work towards a solution – be that social, digital, or political. It is important that those already losing out in the digital age don’t see their finances or wellbeing threatened by the universal credit.