After a crushing defeat in the general election, Labour will now embark on a post-mortem investigation of what went wrong. The immediate response by the party leadership, once the scale of the defeat was known, was to attribute the result to Brexit.

The party’s message on the issue was muddled by trying to straddle the divide between Leavers and Remainers. This approach failed in the European elections in May and has now spectacularly failed again in the general election. The voters wanted Brexit done, and this meant working class Leavers and many Remainers voted Conservative, in order to bring an end to the turmoil.

Since that initial response, the Labour leadership has accepted that it also bears responsibility for the result. Both leader Jeremy Corbyn and shadow chancellor John McDonnell have announced that they will be stepping down from leadership positions.

But both also continue to argue that the party’s positions on issues such as nationalisation, taxation and public spending was basically sound, even if it didn’t reach traditional Labour voters in the “red wall” of constituencies across the north of England. The implication of this is that fresh faces are needed to sell the left-wing agenda but the policies do not need to radically change.

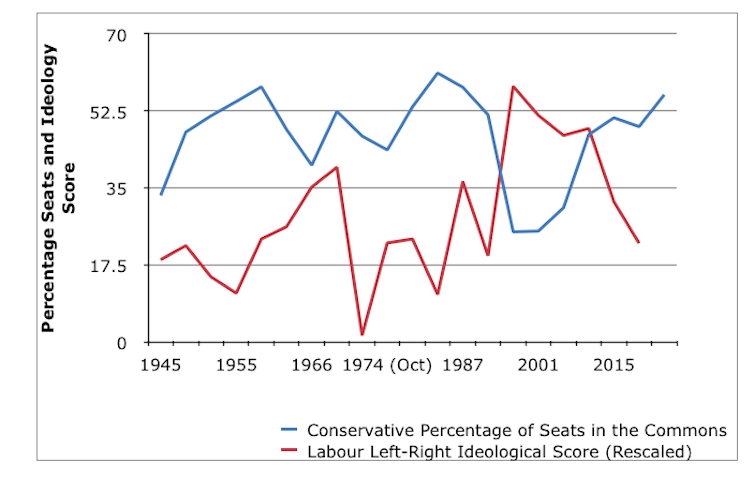

Historical trends suggest otherwise. If you chart the relationship between the percentage of seats in the House of Commons won by the Conservative Party and the policy positions taken by the Labour party on the left-right dimension in British politics in every post-war general election, you can see that the further left Labour goes, the greater the Conservative victory.

It has been a common argument that Labour needs to move towards “the middle ground of politics”, to win again. There is even a formal theory known as the “median voter theorem”, popularised by the economist Anthony Downs which shows why this is necessary. The median voter is the person who has as many voters on their left as on their right on the left-right scale of political views. A key problem with this idea is identifying exactly what the middle ground of politics means in policy terms.

The party manifesto project provides an answer to this question. This is a long-running collaborative research project with political scientists in many countries measuring the policy commitments made by political parties in their election manifestos. It systematically codes a whole range of policies using a technique known as content analysis to create numerical scales. These measure how left wing or right wing political parties are in different elections across the world’s democracies.

The chart below shows how left wing or right wing Labour’s manifestos have been in every election since 1945, with a low score indicating that the manifesto was very left wing and a high score indicating the opposite. It can be seen that the most left-wing manifesto was in the February general election of 1974 and the most right-wing one in 1997 when Labour won a landslide victory. Note that there were two general elections in 1974, one in February and the other in October.

There is a clear pattern. Labour swings to the left after an election defeat, which, in turn, produces a surge in support for the Conservatives. This happened after the defeat of the post-war Labour government in 1951, and again rather dramatically after Harold Wilson’s government was defeated by Ted Heath in 1970. The pattern also re-occurred after Margaret Thatcher won the 1979 election and Labour produced “the longest suicide note in history” – as Labour MP Gerald Kaufmann branded the party’s 1983 election manifesto.

Finally, and most importantly, the sharp swing to the left since 2010 has produced a growing Conservative seat share in the House of Commons. We do not have manifesto data for the 2019 general election yet, but it is a safe bet that it is even more left-wing than the 2017 document.

The correlation between the Conservative seat share and the Labour manifesto scores is -0.57, which means as Labour moves to the left and the ideological score falls, the Conservatives win more seats. Another way of showing the same thing is the correlation between the percentage of seats won by Labour and the left-right scale which is +0.39 – Labour wins more seats when it moves to the centre.

The implication is clear. Replacing the faces on the Labour front bench to try to sell the same left-wing policy agenda is not going to bring electoral victory. A thorough review of policy is needed as part of the election post-mortem.