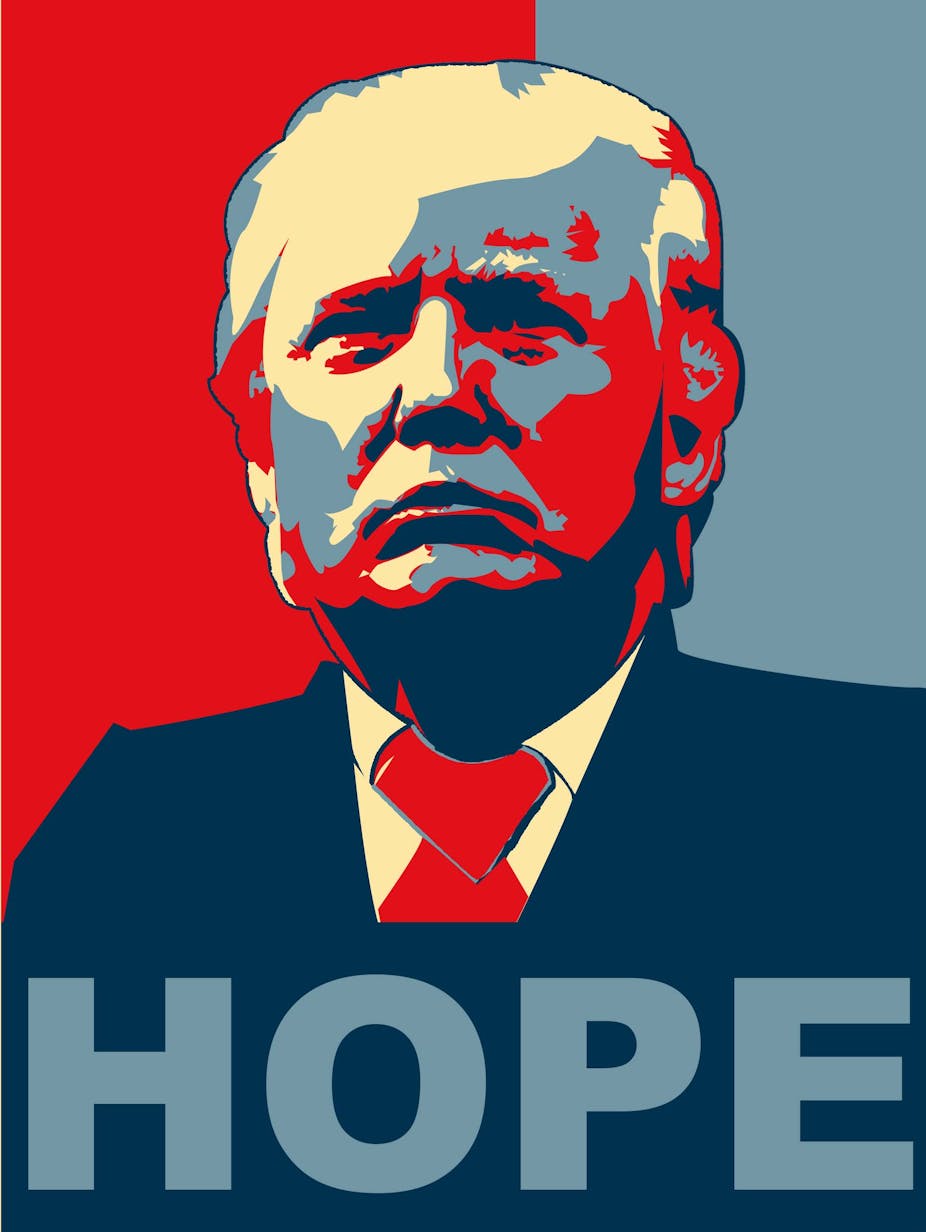

Do you remember that Barack Obama poster? The one of him looking into the middle distance, as if gazing upon a future only he could see, the word “HOPE” spelled out across his chest in blue – the colour of clear days and sunny skies? It was in Obama’s speech at the 2004 Democratic Conference – the one that catapulted him to the presidency four years later – that he first made the audacious promise that the country had the power to choose hope over cynicism. Farewell to the grim ironies of the 20th century, hello to the brave promise of the new millennium.

But Obama’s hope was always a vague one: something to do with slaves, immigrants, soldiers and mill workers. He said it was “something more substantial” than “blind optimism” but didn’t go into the details. It was simply what you harness in the face of difficulty and uncertainty. The thing that keeps you believing that the future will be better than today.

The general public is accustomed to thinking about hope in political terms. That is the American eschatology (the belief in the nation’s ultimate destiny) – that through democracy the country will enter the promised land. Indeed, hope is, at its essence, faith in the future. And people tend to talk about hope, as Obama famously did, assuming a shared understanding of what it means. It is not a loaded term. It is a light one – bright, buoyant, chirpy.

‘No real hope without God’

Or so I thought. John Fea, author of Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump has a different take. For him – an evangelical historian of American politics – hope is not the vague optimism of Obama, but the precise hope of Christian theology. Hope rests on the truth of Jesus Christ. It is, as Christian political philosopher Glenn Tinder described it, a divine gift “anchored in eternity”. There can be no real hope without God.

What Fea bravely does is ask his fellow believers: “Can evangelicals recover this confidence in God’s power – not just in his wrath against their enemies but in his ability to work out his purposes for good?” In other words, can evangelicals set aside the evangelical political playbook, which privileges the pursuit of political power and rests on nostalgia for a mostly mythical past? Can they truly trust in God?

Instead of believing that the only way to safeguard Christian values is to influence legislation – most recently, by making a morally suspect strongman president – what if they actually lived those Christian values instead and let God take care of the rest?

Fea urges his brothers and sisters in Christ to stop chasing political power, to choose history over nostalgia and to replace fear with hope. He offers a Christian approach to politics that rejects the fear, bluster and legislative gamesmanship that underwrote Trump’s rise to power. Instead, Fea takes inspiration from the activists of the civil rights movement.

Their hope was one “forged amid suffering and pain,” he says, resting on a foundation of deep faith and fearless witness. It was not about making things better by electing the right people. It was about being the right people themselves.

Fea argues that evangelical hope has become too secular. It is the hope of Obama – vote for the right party and things will get better – not the hope of Martin Luther King and the everyday heroes of the civil rights movement. In Fea’s arguably romanticised view, their hope was expressed by bearing witness to injustice and allowing God to take care of the rest. They knew that, beyond organising, “something deeper was needed”.

Forget the demigods

Fea urges fellow worshippers to forget the political demigods and return to the original nature of Christian hope. Remember God and remember his son. This, after all, is the essence of hope: the faith in Christ’s sacrifice and the trust that he will return. Fea’s request may seem simple enough, but it is a big ask, because he insists his fellow evangelicals need to relinquish the notion that America is a Christian nation.

He may also be allowing the 81% of evangelicals who voted for Trump (that is the white, non-Hispanic Protestants who self-identify as evangelical) too much benefit of the doubt. By treating them as a group of people who compromised their values for the sake of their faith (a very strange conundrum indeed) he is privileging their “evangelical” identity over their other identities.

His argument presumes all of these white evangelicals acted from a basis in shared Christian beliefs – that they are, when it comes to politics, fundamentally motivated by their Christianity.

By doing so Fea glosses over how, for some of those evangelicals, the term is as much a cultural category as a theological one. For many, it is as much about white entitlement as it is about Jesus. “Evangelical” can serve as cover for sexism, racism, nativism, Islamophobia and homophobia. God is their excuse for hate.

These men and women are unlikely to give up political activism for hymns, volunteer work and prayer. They fear for their way of life, they believe things used to be better (which, thanks to Jim Crow and the post-war economy, for them, they were ) and they want to have power so that other people – who will infringe on their way of life – won’t get it.

This is the chief blind spot in this otherwise impressive book, and I suspect it may be an intentional one. If Fea is hoping to change the hearts and minds of some of the 81% who voted for Trump he dare not speak too harshly. Even so, I have to wonder how much traction his book will find with them, given his rejection of the belief that America was founded as a Christian nation.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter. The book is dedicated to the 19% – the white evangelicals who did not support Trump. And I hope it finds an audience outside evangelical circles as well, among people too accustomed to excoriating rather than listening. Most people are well aware that Islamic extremists don’t speak for all Muslims. So why do so many persist in allowing the most toxic of so-called evangelicals to represent the rest?