When people look back on 2014, it may be best remembered as the year of Ebola. Two previous assumptions – that the virus was confined to remote regions of central Africa, and that the notorious virulence of the disease acted as a kind of self-limiting factor, with epidemics always burning themselves out after their initial flare-up – were shattered. Since its discovery in 1976, Ebola has been a curiosity in virology’s chamber of horrors, but in 2014 it well and truly arrived as a serious player in the global disease-threat league table.

As the world watched apprehensively and then stirred into action, the general impression was that the scientific and medical establishment had no suitable drugs, no vaccine and, some would have it, no clue. The truth, however, is a little more complicated.

Fast-tracked funding has led to a number of high-profile vaccine trials. While one Swiss trial was temporarily halted after a reported side effect of a rash, The Lancet reports that two experimental DNA vaccines to prevent Ebola (and the closely related Marburg virus), trialed for the first time in Africa, are safe. These filovirus vaccines generated an immune response in healthy Ugandan adults, as was previously reported in a US trial.

Tellingly, this latter phase 1 trial began enrolling people in Kampala between November 2009 and April 2010.

Slow speed?

The fact that previously the most westerly appearance of the Zaire variant of Ebola was nearly 5,000 kilometres away in Gabon and that one of the endemic viruses to pop up in Guinea every year is the similar but considerably less lethal Lassa fever, certainly contributed to the three-month lag between the first cases of Ebola and the official recognition of the outbreak.

But virologists have not been neglecting Ebola – in the 37 years since the virus was first identified, a large chest of potential treatments and vaccines have been developed, which were in various stages of progress when this year’s outbreak took hold. The fact that none of them had yet reached the stage of approval required for full commercial release, was more a consequence of the relatively small number of Ebola victims in a world where other viruses – HIV, hepatitis C, and influenza, to name the worst culprits – were killing millions, rather than any deliberate callousness on the part of pharmaceutical researchers and companies.

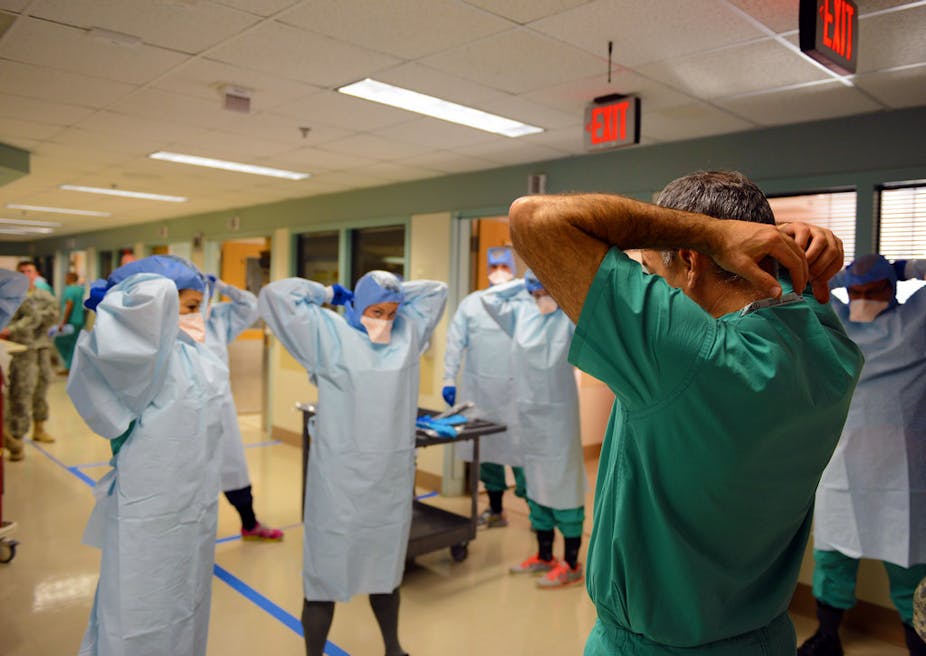

Nor were public health officials exactly fumbling around in the dark. Nearly four decades of dealing with smaller Ebola emergencies had produced a cadre of well-drilled outbreak response workers who knew exactly what steps to take to bring the virus under control. The only problem – and certainly a big one given the scale of this outbreak – was that these methods had previously only been tested in outbreaks numbering dozens, or at worst a couple of hundred cases, generally in well defined locations. Scaling these methods up to an outbreak area encompassing three countries was a task of unprecedented proportions.

Perhaps, after nearly nine months of struggle, the outbreak is finally coming under control, and governments and pharmaceutical companies will be much more prepared if there’s another epidemic in the future. The story is far from over, however. To reduce the outbreak to manageable levels is a triumph, but moving on to completely extinguishing the disease in West Africa may prove to be an equally gargantuan task. In the meantime, there is much we can, and must, learn to prevent a similar, or worse, recurrence in West Africa or elsewhere.