Ello is enjoying its moment of fame – in part thanks to its use of the latest fad in corporate legal structures.

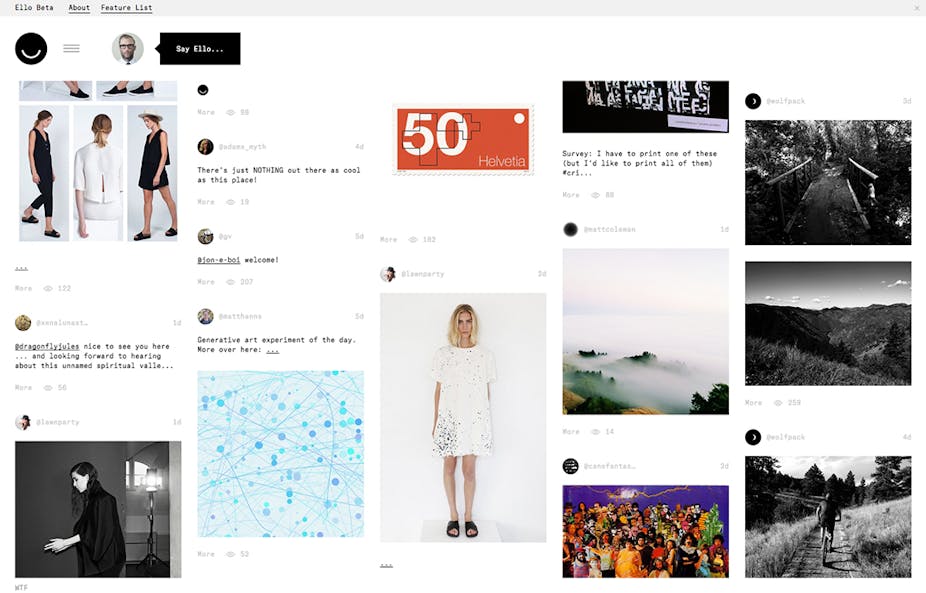

The eight-month-old social network is still in beta, and has nothing like the brand recognition of Facebook. Yet it is the fastest-growing social network in the world and just received a US$5.5 million capital infusion from several venture capital firms.

Ello’s founders say this is because the invite-only website offers a better business model for social networks – one without the involvement of advertisers. They also say they have guaranteed that Ello will always remain true to this commitment by converting to Delaware public benefit corporation status, a new type of for-profit company that barely existed a few years ago.

Delaware created the public benefit corporation in 2013. For-profit firms that incorporate using this new form have a dual purpose. They pursue profits like any other company but also identify in their corporate charters some kind of social mission – the “public benefit” from which their name derives. Ello’s charter promises it will “never make money from selling ads [or] using data.” This charter will indeed limit Ello’s activities, unless it is changed by a supermajority shareholder vote.

A balancing act

The statute also gives unique instructions to directors of public benefit corporations. As the directors engage in oversight, they must balance the financial interests of shareholders, the interests of other stakeholders affected by the firm’s conduct and the public benefit the firm identifies in its charter. In Ello’s case, remaining ad-free would fall into either of the last two categories.

Corporate law already gives for-profit directors a great deal of discretion to make business decisions. If Ello’s directors were so inclined, ordinary corporate law would certainly allow them to choose an ad-free business model for their social network. Corporate directors can be confident the courts will respond to such actions favorably, as long as the process is transparent and there are no conflicts of interest.

Ad-free forever

So why did Ello’s founders feel the need to go the public benefit corporation route? Because they wanted more than mere permission; they wanted to lock in their stance against advertising revenue forever.

Particularly worrisome for them is the potential for a change of control. If the company’s directors were faced with the prospect of a bid from buyers wishing to purchase enough shares to change the charter and pursue ad revenue, standard for-profit corporate law could limit their discretion. Under Delaware law this would likely happen. While other states have statutes that allow directors considering a takeover to take into account the interests of a wide range of constituencies, including customers, employees and the broader community, Delaware has no such constituency statute. Incorporating there means directors risk liability if they take actions to stifle a transaction that would create value for shareholders.

More latitude

Incorporating under the new public benefit statute provides Ello’s directors with more latitude. Directors may rebuff a proposed sale and erect defenses against it, even if doing so will harm the pocketbooks of its shareholders. They may do so to pursue their stated public benefit or even to protect the interests of the many other parties the firms’ conduct will affect – such as its existing, ad-disdaining users.

Of course, directors who want to stay true to the ad-free model – or an environmental or social commitment – would also be protected by adopting the same types of charter provisions and incorporating in one of the dozens of states with constituency statutes on the books. With public benefit corporation status, though, they can buttress their ad-free model in Delaware, considered the gold standard for incorporation.

Importantly, however, nothing in the Delaware public benefit statute will compel Ello’s future directors to put retaining the ad-free model before the other competing interests they must weigh – either in response to a takeover bid or for any other reason. Public benefit corporation directors are obligated only to continue managing the corporation in a way that balances the shareholder interests, stakeholder interests and public benefit. They need not prioritize their chosen public benefit at every turn or even overall. They can even change or abandon public benefit status, as long as enough shareholders agree.

Shareholders considering such a charter revision could reject it, and could even be sufficiently incensed that they would vote out the board. However, they could also react by approving the change, selling their (presumably more valuable) shares, and investing elsewhere.

Corporate structure isn’t everything

Founders concerned about locking in a business model that might leave potential revenues on the table, whether by refusing advertising, fossil fuels or offshore workers, should not count on a statute book alone to protect their vision. Instead, they should carefully select managers and investors who share these commitments and use contracts and creative financing structures to lock in those commitments over a time frame they can live with. Ello, whose Series A funders signed a document “vowing” to support its ad-free mission and made statements like “we’ll either build a business that doesn’t rely on third-party advertising or the selling of user data or we won’t build a business,” is doing this already.

Only time will tell how long Ello’s commitment to an advertising-free business model can last. Any longevity it does achieve, however, will have more to do with the shared vision and contractual commitments of its founders, managers and investors than with its new legal status.