Making a drug is like trying to pick a lock at the molecular level. There are two ways in which you can proceed. You can try thousands of different keys at random, hopefully finding one that fits. The pharmaceutical industry does this all the time – sometimes screening hundreds of thousands of compounds to see if they interact with a certain enzyme or protein. But unfortunately it’s not always efficient – there are more drug molecule shapes than seconds have passed since the beginning of the universe.

Alternatively, like a safe cracker, you can x-ray the lock you want to open and work out the probable shape of the key from the pictures you get. This is much more effective for discovering drugs, as you can use computer models to identify promising compounds before researchers go into the lab to find the best one. Now a study, published in Nature, presents detailed images of a crucial anti-ageing enzyme known as telomerase – raising hopes that we can soon slow ageing and cure cancer.

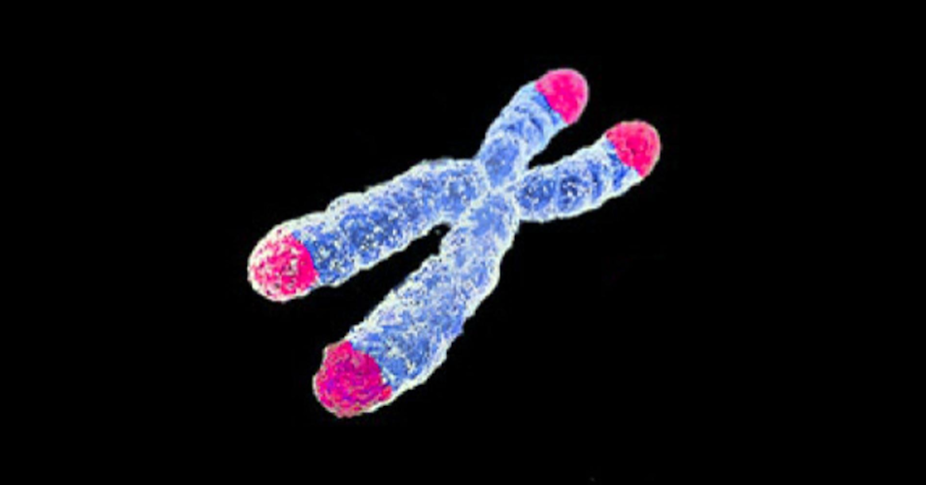

Every organism packages its DNA into chromosomes. In simple bacteria like E. coli this is a single small circle. More complex organisms have far more DNA and multiple linear chromosomes (22 pairs plus sex chromosomes). These probably appeared because they provided an evolutionary advantage, but they also come with a downside.

At the end of each chromosome is a protective cap called a telomere . However, most human cells can’t copy them – meaning that every time they divide, their telomeres become shorter. When telomeres become too short, the cell enters a toxic state called “senescence”. If these senescent cells are not cleared by the immune system, they begin to compromise the function of the tissues in which they reside. For millennia, humans have perceived this gradual compromise in tissue function over time without understanding what caused it. We simply called it ageing.

Enter telomerase, a specialised telomere repair enzyme in two parts – able to add DNA to the chromosome tips. The first part is a protein called TERT that does the copying. The second component is called TR, a small piece of RNA which acts as a template. Together, these form telomerase, which trundles up and down on the ends of chromosomes, copying the template. At the bottom, a human telomere is roughly 3,000 copies of the DNA sequence “TTAGGG” – laid down and maintained by telomerase. But sadly, production of TERT is repressed in human tissues with the exception of sperm, eggs and some immune cells.

Ageing versus cancer

Organisms regulate their telomere maintenance in this way because they are walking a biological tightrope. On the one hand, they need to replace the cells they lose in the course of their ordinary daily lives by cell division. However, any cell with an unlimited capacity to divide is the seed of a tumour. And it turns out that the majority of human cancers have active telomerase and shorter telomeres than the cells surrounding them.

This indicates that the cell from which they came divided as normal but then picked up a mutation which turned TERT back on. Cancer and ageing are flip sides of the same coin and telomerase, by and large, is doing the flipping. Inhibit telomerase, and you have a treatment for cancer, activate it and you prevent senescence. That, at least, is the theory.

The researchers behind the new study were not just able to obtain the structure of a proportion of the enzyme, but of the entire molecule as it was working. This was a tour de force involving the use of cryo-electron microscopy – a technique using a beam of electrons (rather than light) to take thousands of detailed images of individual molecules from different angles and combine them computationally.

Prior to the development of this method, for which scientists won the Nobel Prize last year, it was necessary to crystallise proteins to image them. This typically requires thousands of attempts and many years of trying, if it works at all.

Elixir of youth?

TERT itself is a large molecule and although it has shown to lengthen lifespan when introduced into normal mice using gene therapy this is technically challenging and fraught with difficulties. Drugs that can turn on the enzyme that produces it are far better, easier to deliver and cheaper to make.

We already know of a few compounds to inhibit and activate telomerase – discovered through the cumbersome process of randomly screening for drugs. Sadly, they are not very efficient.

Some of the most provocative studies involve the compound TA-65 (Cycloastragenol) – a natural product which lengthens telomeres experimentally and has been claimed to show benefit in early stage macular degeneration (vision loss). As a result, TA65 has been sold over the internet and has prompted at least one (subsequently dismissed) lawsuit over claims that it caused cancer in a user. This sad story illustrates an important public health message best summarised simply as “don’t try this at home, folks”.

The telomerase inhibitors we know of so far, however, have genuine clinical benefit in various cancers, particularly in combination with other drugs. However, the doses required are relatively high.

The new study is extremely promising because, by knowing the structure of telomerase, we can use computer models to identify the most promising activators and inhibitors and then test them to find which ones are most effective. This is a much quicker process than randomly trying different molecules to see if they work.

So how far could could we go? In terms of cancer, it is hard to tell. The body can easily become resistant to cancer drugs, including telomerase inhibitors. Prospects for slowing ageing where there is not cancer are somewhat easier to estimate. In mice, deleting senescent cells or dosing with telomerase (gene therapy) both give increases in lifespan of the order of 20% – despite being inefficient techniques. It may be that at some point other ageing mechanisms, such as the accumulation of damaged proteins, start to come into play.

But if we did manage to stop the kind of ageing caused by senescent cells using telomerase activation, we could start devoting all our efforts into tackling these additional ageing processes. There’s every reason to be optimistic that we may soon live much longer, healthier lives than we do today.