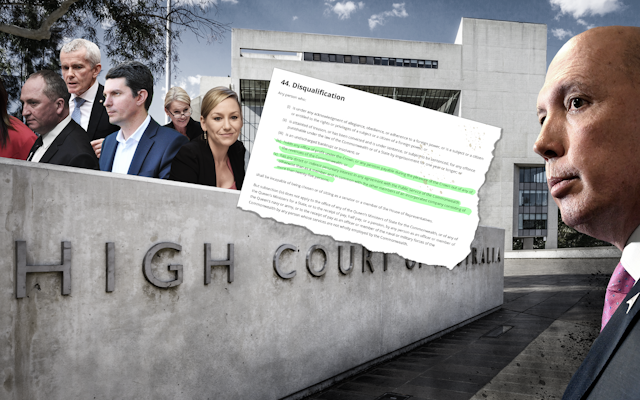

Among the many lessons the recent Liberal leadership spill has taught us is that the problems arising from section 44 of the constitution, which already has quite a hit list, have not gone away, and there may be more to come.

The section deals with disqualifications from parliament. The problems with it have not gone away, but have become part of the political struggle. They are also not only about citizenship, nor are they simply a matter of doing the paperwork.

It is not clear what the disqualification provisions are, or how they are enforced. And, finally, the problem is not going to be resolved if politicians continue to ignore it.

When section 44 issues were first raised, then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull tried to use them as a way of attacking his parliamentary opponents. The ALP is now repaying the favour. Both sides have been more interested in using the issue as a weapon than reaching a solution.

Read more: Could Section 44 exclude Tony Abbott and Barnaby Joyce from parliament?

More than dual citizenship

The original disqualification questions were about holding foreign citizenship. But it is now being asked if the special jobs created for Tony Abbott and Barnaby Joyce breach the “office of profit” provisions, while Peter Dutton’s business dealings have come under scrutiny for a potential s44 breach.

Meanwhile, the question of disqualification on the basis of an entitlement to foreign citizenship, or to its “rights and privileges”, remains unaddressed. If the High Court were to look into the cases of the MPs with such entitlements, and to rule consistently with its earlier decisions, up to a third of the parliament could be disqualified.

But the whole issue is clouded in uncertainty. The section is very badly drafted; partisan conflict has meant that few cases have made it to the High Court and, when they have, the court’s judgments have been, in Jeremy Gans’s words, “too rare, sparse and cryptic for anyone to confidently rule most Australians in or out” of eligibility.

Different judges have reached different conclusions on the same cases. Even those who have agreed with the other judges have done so for different reasons, so no consistent rule can be derived from the case.

Judges are more interested in reaching a decision on the case in front of them than articulating a general rule that can guide future action. So while QCs may make declarations about how the High Court would rule in any case put to them, as the Commonwealth Solicitor-General said on the Dutton case, “it is impossible to predict” how the High Court will rule on a particular case.

The fact that no one is responsible for applying and enforcing these provisions exacerbates the uncertainty. While section 34 on qualifications is amplified by the Electoral Act and administered by the Australian Electoral Commission, there is no comparable authority for determining disqualifications.

The constitution provided three avenues: the ancient right of parliament to determine if members were qualified to sit; some ways in which the High Court could determine disputes as a Court of Disputed Returns; and the possibility of lawsuits by citizens against members whose eligibility was challenged.

This has meant there is no consistent enforcement. The AEC has refused to involve itself in judging disqualifications. The parliamentary power to determine is completely discredited by the partisan motivation of the politicians. The High Court will only hear cases brought within 40 days of the election unless these are referred by parliament. And the first time anyone used the Common Informers Act, the High Court sniffily declared the act was not properly drafted and was in breach of the constitution. The court threw out the case, nullifying the provision specifically inserted in the constitution to give ordinary citizens the right to enforce the disqualification rules through the courts.

Turnbull announced that all MPs would be asked for a declaration that they were not disqualified by reason of holding a foreign citizenship. These declarations were recorded in a citizenship register, but no action was taken as a result. The register appeared to be an empty gesture.

So we have rules on disqualification that are applied only to those who are honest enough to resign or unlucky enough to find a parliamentary majority organised to refer their case to the High Court.

The multiparty parliamentary committee investigating the problem (the third one to do so) concluded (like its predecessors) that section 44 is not fit for purpose. It proposed a constitutional amendment to put the determination of disqualifications back into the hands of parliament. But Turnbull rejected this proposal before the committee had even proposed it.

Where do we go from here?

Probably everyone in Canberra is too shell-shocked right now to think of more than surviving the upcoming election. But, after the election, the best starting point would be the parliamentary committee’s recommendation to put responsibility back into parliamentary hands. This would enable work to begin on how best to deal with the tensions arising from citizenship, public employment, business dealings and so on, and what sort of regulatory structure would be most appropriate.

The question is how to overcome the inertia and partisan opportunism that have impeded the search for a resolution of the problem up to now. The most promising course would be the development of a cross-party advocacy network, building on the work of the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters. It would help if members of the public were to write to or ring their MPs and senators to express their concerns.

Read more: Explainer: is Peter Dutton ineligible to sit in parliament?

If this sounds too unambitious, those with the energy to do so could organise to challenge, within the 40-day window, the election of all those members and senators who are entitled to another citizenship or to its rights and privileges.

How many were caught in this net would depend on how many of the present representatives were re-elected, but it would probably not be less than 20-25% of the parliament. For them, the exclusion would be permanent, because while a foreign citizenship can be renounced, an entitlement cannot be: it remains in the law of the foreign country, and the High Court recognises foreign law as the determinant of citizenship status.

The possibility of having a quarter of the parliament thrown out in this way might just be enough to induce the parliamentarians to support a move to a better system.