You can also read this article in Welsh.

In the year ending September 2022, more than 70,000 people had claimed asylum in the UK. The vast majority were from countries that do not use English as a first language.

Being able to communicate in English is essential for newly arrived migrants. People who have gone through traumatic experiences are, understandably, often desperate to build new lives. They want to use the skills and knowledge they have to access work and education. To do that, they have to navigate the health, social security, housing and education systems.

Language is the single most important area that can promote integration for migrants. My research has shown that language teachers are uniquely placed to positively affect the lives of people in these situations.

In fact, the 2016 Casey review, a government-commissioned report on the state of social cohesion in Britain, highlighted that developing fluency in English is critical to integration.

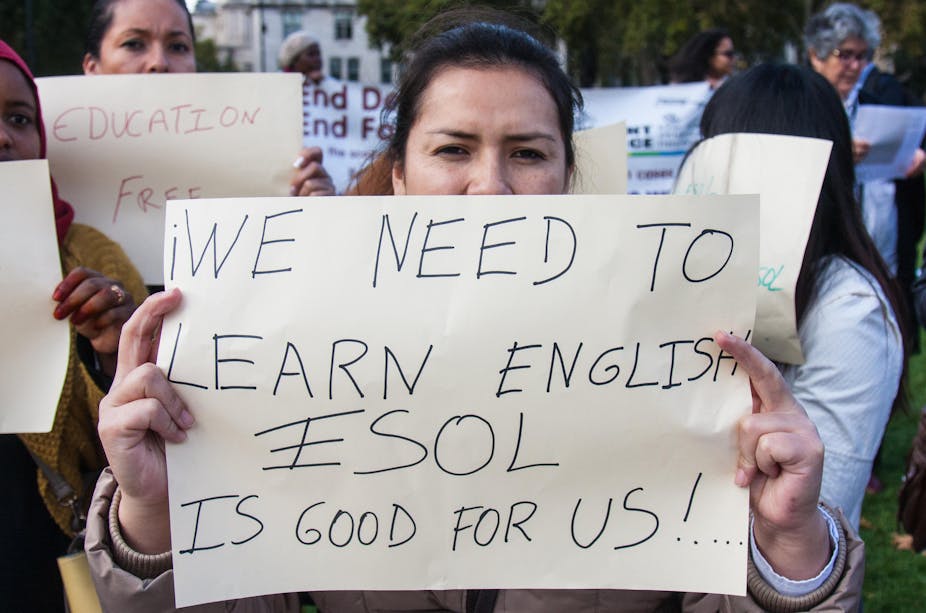

Given its importance, refugees and people seeking asylum are often keen to enrol in English for Speakers of Other Languages (Esol) classes. And these classes can provide more than language tuition alone. They are a social space, providing a sense of structure to daily lives, offering both linguistic and psychological support.

But cuts to adult education budgets following the change of government in 2010, and the introduction of austerity, mean access to Esol language support is often difficult. There can be long waiting lists and too few classes available.

Also, the way adult education is funded in the UK means teachers are obliged to follow an assessment system to measure language competence. That constraint frequently results in classroom time being focused more on passing exams than on developing fluency or bestowing a warm welcome and sense of belonging.

While coping with the demands of building a life in a different country through a new language, many Esol learners are also dealing with the trauma associated with forced displacement. That’s on top of the stress involved in navigating an often hostile and complex asylum system.

Such challenges mean Esol teachers can be a vital bridge to the new society. And the Esol classroom can be the prime location for getting information and for creating the bonds needed for successful integration. With that in mind, how Esol classes are organised and managed is fundamental to a person’s success in learning English and all the associated opportunities.

However, providing Esol classes, primarily through colleges of further education, is a hugely bureaucratic undertaking. This often results in the potential of Esol classes to promote integration being missed.

One of the reasons is that these classes are funded in the same way as other adult education subjects. Accordingly, teachers must follow a curriculum that provides evidence that learners are progressing. This results in teachers putting their efforts into preparing students for constant tests and assessments. And that leaves little time to address the real-life concerns, needs and interests of their migrant learners.

It also means the opportunities to bring about a sense of belonging are instead replaced with learning about matters such as verb conjugations and the English tense system.

Changes are needed to both the way Esol is funded and organised, and to the way Esol professionals are educated to view the language classroom.

Solutions

Removing some of the requirements to produce evidence of learning would shorten teacher administration time. It would also relieve the pressure on students and teachers to be constantly preparing for the next assessment. This would allow more time to focus on discussing issues of relevance to the learners.

There is much support from language experts for viewing Esol from this more human perspective. It is an understanding of the classroom that resonates with educators who have been advocating for a participatory pedagogy – which involves more collaboration and decision making among students – for Esol since the turn of the century.

This style of teaching focuses classroom content on the lives of learners. Examples of typical issues that dominate such discussions include the challenge of finding meaningful employment, the effects of trauma, culture shock, separation from family, money worries and finding accommodation.

This means more time is taken up with learners using language to express thoughts, anxieties, hopes and concerns that affect their new lives. And far less time is used by the teacher striving to cover an externally imposed syllabus.

Thinking afresh about language education for forced migrants means considering how a participatory approach may be an effective way to welcome newcomers and help with their integration. With little effort, language education for migrants could allow space for the development of projects that bring people together. It could foster friendship and understanding while also promoting language development.

Esol is not just another academic subject, it is the most important area that promotes integration. But, at present, opportunities to provide holistic, person-centred language education to people seeking refuge in the UK are being missed because of the overly bureaucratic and exam-focused system that prevails.