The promised referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU is now firmly on the parliamentary agenda. Opening parliament on May 27, the Queen announced that the government would introduce early legislation to enable a vote to take place as well as measures to renegotiate the UK’s place in the EU.

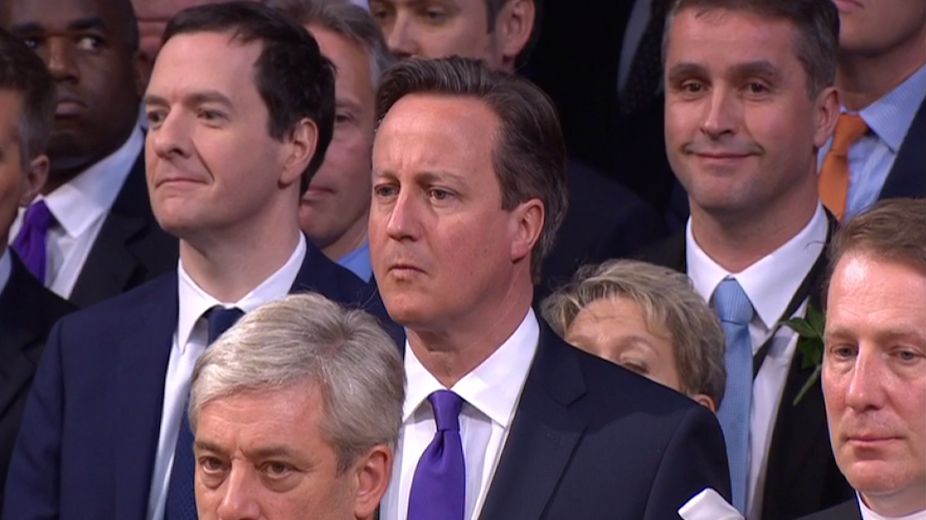

The referendum is now sure to happen before the end of 2017. This conveys a sense of urgency. The law may even be introduced as Cameron travels around Europe to negotiate with partners. He has back-to-back meetings with the leaders of Denmark, the Netherlands, France, Poland and Germany in the days following the Queen’s speech.

By the time of the next EU summit in June, Cameron will have put his case forward to all the EU leaders, and by then we should have a clearer picture of what exactly he wants and which proposals are most likely to be accepted in the EU.

Cameron is in a real hurry to broker a deal that would be acceptable to both the British public and to EU partners. Although the precise date of the referendum has not yet been announced, it seems he wants to avoid the referendum taking place in 2017 as this would coincide with the German and French elections.

With rising protest in both countries, neither Merkel nor Hollande are likely to want to renegotiate with the UK during their election campaigns. Hollande in particular faces the challenge of taking on the far-right Front National – which is becoming a real electoral threat – and will be vulnerable to criticisms if he makes concessions.

Renegotiation

While the referendum issue is relatively clear cut, the government has left itself plenty of room for manoeuvre when it comes to renegotiating the UK’s relationship with the EU. It is clear that the UK’s membership of the EU depends on the consent of the British people but the Queen’s speech was quite broad and did not mention any specific red lines that the government would find non-negotiable. This will give Cameron quite a bit of leeway when presenting to the electorate the actual renegotiation package.

The Queen’s speech stated that the government would pursue reform of the EU “for the benefit of all member states”. The government is here seeking to paint a picture of the UK as a benevolent nation and not the selfish EU partner it might appear to be at times. Renegotiation, we are to believe, is being pursued in the spirit of benefiting the entire alliance rather than just British interests.

Another interpretation though, is that the UK is seeking to take the EU in a specific direction that may or may not be acceptable to other member states. It might even be seen as trying to impose its own way of governing the EU on its partners. It is extremely unclear how the UK intends to renegotiate in the interests of all EU partners – particularly since real negotiation is yet to take place.

The months ahead

The road ahead is bumpy. Angela Merkel and Hollande have already agreed between themselves on fostering closer political ties among the eurozone member states without re-opening the European treaties. That sends a strong signal to Cameron that there is little appetite for treaty revision.

Another key issue is how the referendum question will be phrased. Both sides of the debate will be sensitive to how the wording could push voters in a particular direction. “Should the UK remain a member of the EU?” is one option, but it is positively phrased and Eurosceptics might argue that voters are being prompted to agree.

But beyond the specifics of the debate, the Queen’s speech has given one clear signal: the UK’s relationship with the EU will be one of the defining issues of this government and potentially for decades to come.