I’ve been conducting scientific research with experts who specialise in advanced microscopy at Nottingham University for more than ten years. But I’m not a scientist – I’m an artist and lecturer in illustration.

Despite their importance in education and society, science and art are often seen as distinct fields, which, in my opinion, stifles beneficial connections. I want to foster these connections by helping to make sense of scientists’ work for a wider audience through my own work as an artist. I have seen the enormous potential that exists when scientists and artists work together.

Like advanced imaging specialists, I am fascinated by light, colour, lasers, technology and science. When I discovered the Wellcome Trust’s Sci-Art scheme in 1998, its ethos – to foster connections that produce art directly inspired by science – encouraged me to seek out life scientists to collaborate with, because the methods we employ to create images are connected.

Advanced imaging specialists and myself both have knowledge of light, optics and computer visualisation methods, while I am fascinated by how I can use scientific image data innovatively. There has always been a lack of understanding between art and science in terms of approaches to imaging and its potential. I wanted to discover if and how an artist-researcher could contribute to new methods and approaches through collaboration.

My aim was to dismantle silo mentalities so that artists can work with scientists to create new representations, insights and behavioural change. I wanted to use experimentation and play – elements that helped me negotiate and interpret our collaboration in new ways by extending artistic and scientific methods of visualisation. This led to new and different representations, technological advancements and better intellectual and visualisation skills.

I advanced three methods of production: an introspective, digital drawing method using limited tools; data montages where data and documentary footage are explored; and experimental moving image work, integrating documentary film footage and sound.

Getting in on the science

Advanced microscopy is used to observe cells that the naked eye cannot see, while being as gentle as possible on the object being examined. My work focuses on the imaging potential of the biomedical data revealed through advanced microscopy. This artistic expression of scientists’ data can provide them with tools for showing their work in a different way to a different audience.

For example, I work with scientists while they conduct image experiments, to discover how and why they generate image data of cell behaviour. In a nutshell, my research seeks to break down barriers and boost collaboration so that artists and scientists can see the other’s work from a different perspective.

However, these scientists devote their lives to medical research and have little opportunity to interact with colleagues from other disciplines. But my presence as an artist helps to bridge this gap and supply fresh insights that alter the way I, and everyone around me, see scientific images.

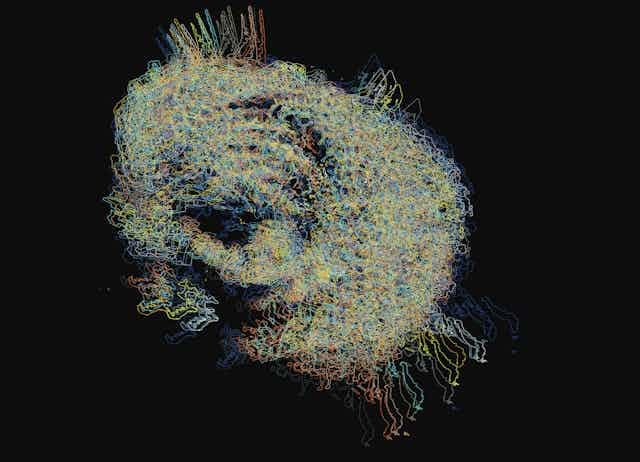

My observations spark new depictions of cells, biological structures and skin, (see images above and below). For example, I use digital sketching to map the structural complexity of biological structures such as radiolaria – minuscule single-cell marine creatures with a delicate mineral skeleton made of silica (shown in the opening image).

Inspired by watching these scientists at work I create data montages, seeing unique patterns, wonderful colours and movement through layers of skin at this detailed magnified size (as seen below). I then display my artwork along with advanced microscopy photographs at scientific conferences to compare results and highlight the aesthetic potential of scientific data from an artist’s perspective.

I’ve worked with four science labs since 2010, including the Centre of Membrane Proteins and Receptors at Nottingham University; the Imaging and Analysis Centre at the Natural History Museum, London; the Centre for Cellular Imaging in Gothenburg; and Biofilms Research Centre for Bio-interfaces in Malmo, Sweden.

In these lab relationships I have helped scientists at different stages of their careers communicate their discoveries more accessibly through my artistic interpretations. I have created graphic artwork and experimental films that showcase the dynamic nature of imaging technology. It has allowed me to portray the unrealised visual potential to help illuminate complex processes.

At the Centre for Cellular Imaging, I collaborated with specialists who work at the intersection of life and material sciences on an international study to better understand how medicine is absorbed and distributed via the skin.

As researchers on the same project, we discovered numerous similarities, such as our interest in technology and our fascination with microscopic imagery. However, we approached science from a completely different angle. While scientists were busy documenting their results, I was captivated by the real-time visual depictions on the computer screen.

Benefits for everyone

Over a decade of merging science and art, I’ve discovered three major advantages to such collaborations.

1. The variety of collaborations increased my appreciation for technical advances in scientific visualisation.

2. They inspire both scientists and artists to think creatively.

3. They contribute to making science more accessible to the general public.

Alice Twemlow, lecturer in design at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague has stressed the educational importance of this research, because it fosters new kinds of learning via art, science and technology.

My work has even made it into popular culture, appearing in BBC4’s The Beauty of Anatomy. And London’s Coningsby Gallery recently hosted a public show of my graphic artwork. I believe this helps to make science appear less remote and more approachable for the general public.

In a world where innovation thrives at the intersection of disciplines, every science lab should welcome the presence of an artist. Together, they can explore the enormous potential of arts-science collaboration to spark creativity, deliver ground-breaking discoveries and make that knowledge accessible to a wider audience.