The sweeping advance of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) has given rise to a lively debate about who should bear ultimate responsibility for the disintegration of Iraq and Syria. On one hand, many commentators have pointed the finger at George W Bush and Tony Blair who, they argue, as the architects of the 2003 invasion, fundamentally destabilised Iraq and ultimately led to the current crisis.

The ISIS jihadis themselves have made political capital out of their professed overthrow of the 1916 agreement between Britain and France that carved up the Ottoman Empire and created the somewhat artificial borders which now appear to have been transcended.

This is a false debate. It is not an “either-or” situation. Actors in both 1916 and 2003 have contributed – in very different ways – to today’s Middle East chaos.

Imperial gambit

The “Sykes-Picot Agreement” (and it was only an agreement) was negotiated between the French diplomat François Georges-Picot and his British counterpart Sir Mark Sykes between 1915 and 1916. Its objective was to ensure that, after the final defeat of the Ottoman Empire, the vast expanse of territory stretching from the Gulf to the Mediterranean and from the Red Sea to the Caspian should neither fall into hostile hands nor dissolve into chaos. British interests in the overland route to India, and French interests in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant required that “Arabia” be run from London and Paris.

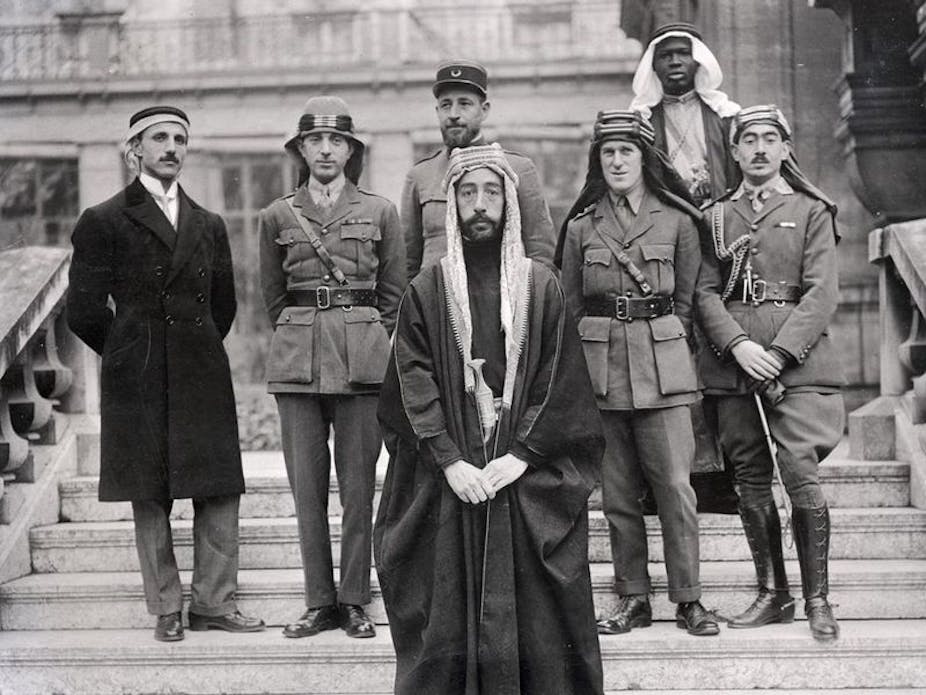

This agreement was reached in great secrecy because – in parallel – the British were offering much of the same territory to Arab leaders, in particular the Sheriff of Mecca, Husayn bin-Ali, in exchange for Arab participation in the war against the Turks – the story of Lawrence of Arabia. This duplicity was completed by further British promises to Lord Rothschild of a homeland for the Jewish people in Palestine – also partly driven by a quest for Jewish support for the war.

Sykes-Picot is significant in the current context more in the symbolism than in the substance. What it amounted to was the two colonial empires remaining intact after World War I arrogating to themselves additional colonial possessions against all the principles of self-determination which had been so passionately pursued by Woodrow Wilson both as a condition for US entry into the war and at the Treaty of Versailles. Imperialism and self-determination are strange bedfellows.

In the case of the territories formerly known as Mesopotamia, which were granted to Britain under a League of Nations mandate, the situation was further complicated by the state of effective bankruptcy in which the UK emerged from the war. Winston Churchill, as the colonial secretary in Lloyd George’s government, had to find a way of running these territories on the cheap. It was therefore decided, at a meeting in Cairo in March 1921, to create a new country – Iraq – out of three of the pre-existing vilayets (provinces) of the Ottoman Empire, to bestow upon it a king, and to try to make it work in Britain’s interests.

Not a viable state

This was always going to be a tall order. The three provinces chosen were the Shia Arab lands around Basra in the South; the largely Sunni Arab districts north and west of Baghdad in the Centre; and – eventually (Churchill went back and forth over the wisdom of this particular move) the Sunni Kurdish areas in the North. Under the Ottomans, these three provinces had had virtually nothing to do with one another.

They embraced cross-cutting sectarian divides (Sunni and Shia, Arab and Kurd). The actual borders drawn, both in the West (abutting Syria and Jordan) and in the North (abutting Turkey and Iran), made very little sense either geographically or socio-culturally. The king placed on the throne (Faisal, son of Husayn) was not only imported from Mecca, but was a Sunni in a country with a large Shia majority. “Iraq” was off to a very bad start.

Nobody ever succeeded in gluing Iraq together or in forging a national (as opposed to a sectarian or provincial) identity. A succession of regimes – monarchical, republican, Ba’athist – tried to make it make sense. Military coup followed military coup during the 1950s and 1960s. Eventually Saddam Hussein took over control in 1979 and ruled the country with a fist of iron. The question of where Iraq might be today if Saddam were still in power is, unfortunately, an imponderable counter-factual.

That Bush and Blair burst, with overwhelming military might, into a volatile and scarcely viable polity – with a war-plan (regime change) but no plan whatsoever for what happened next – is obviously also a major factor in the current chaos. For Blair to deny this is disingenuous at best, scandalous at worst. But for commentators to deny that Sykes-Picot must also be held responsible is to refuse to see the deep original fissures in the edifice.

Large swathes of the former Ottoman Empire (Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, but also, under Italian control, Libya) were dealt with in a manner quite similar to that which Churchill adopted for Iraq.

Those chickens also are suddenly coming home to roost.