Australian visual artist Sue Ford built a reputation as a feminist maverick through her 23 solo exhibitions from 1964 until her death in 2009, and a major exhibition of her work is on display at the National Galley of Victoria until August 24. As a survey of her legacy, it allows a unique overview of the artist’s whole work. It is a pity she never got to see it.

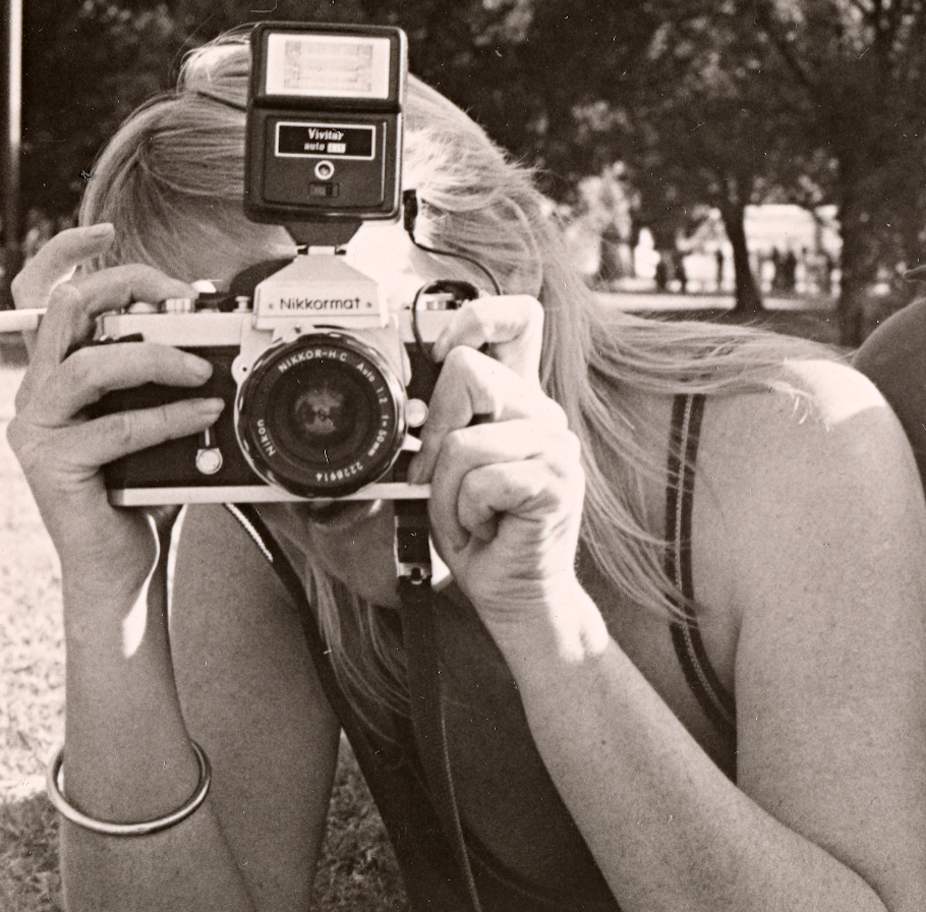

As an avant-garde film-maker, photographer and visual artist, Ford was not interested in commerce – but she was keenly concerned to place women artists working in all media in the spotlight.

The exhibition mainly focuses on her largest body of work – photography – but there is an important story about her work in film that is only slightly touched on in the exhibition.

Ford’s films are of significant interest to Australian film history, particularly for her participation in feminist film collectives.

In Australia in the 1970s there was a boom of feminist film production and Sue Ford was at the forefront as an early and active member of The Feminist Film Workers (1970s-1980s), Reel Women (1979-1983) and Women’s Film Unit (1984/5).

There was enormous energy and enthusiasm within feminist film making groups for the important project of enabling women to gain access to film production, training, and giving a voice to women’s perspectives and issues.

The exhibition includes an image of key members of one of these groups, Reel Women, who are pictured working out of the boot of filmmaker Claire Jager’s old ute.

Also in the retrospective is one of the films from the collective, Ford’s 1972 short film Woman in a House. This was one of the most successful films of the Reel Women collective in terms of popular distribution. Woman in a House is an experimental film. It was made with the first of three grants Ford received from The Experimental Film and Television Fund (EFTF), administered at that time by the Australian Film Institute (AFI).

This fund was important in supporting those in the avant-garde and also, many film makers who became important to the revival of Australian cinema in the 1970s, including Bruce Beresford, Peter Weir, Jan Chapman and Philip Noyce.

Woman in a House explores the female condition through its portrayal of the lot of a housewife. It recalls the experience of enclosure and domestic space, a claustrophobic and wretched view of domesticity. The film speaks of isolation, domestic violence, and debunks the suburban dream through confronting the audience with its reality.

In 2008 Sue Ford herself told me the interesting story behind the grant for this film, in relation to the arts in Australia.

In the early 1970s the Australia Council was funding the arts, and artists, and they received grants paid directly to them in lump sums. However, filmmakers received monies via the EFTF. According to Ford, in order to collect her grant, she had to go down to the AFI offices in Carlton and get a “pink slip”.

This was a kind of purchase order used to buy stock, or have it developed. So where other artists might have been able to fund some of their living expenses from arts grants in 1972, filmmakers weren’t able to do so.

There are only six film works showcased in the retrospective, which does not do her filmmaking legacy justice. But the exhibition illustrates well the themes explored throughout her films, photography and multimedia. There is a wonderful catalogue containing the work and several essays, including one from Marcia Langton which notes that in “the 1980s Ford’s ethical quest led her to Aboriginal people”.

Ford’s work crossed genres, including portraiture, documentary and landscapes. Her films clearly reveal and emphasise her humanist and ethnographic preoccupations – see, for example, Mind of Tibet (2003) – particularly through an interest in the human form, especially the face, see Faces (1976). Signage within the exhibition quotes Ford:

Everybody’s face tells you about the society they live in, and what they’re feeling inside … faces are maps.

Ford’s “maps” have a lot to tell us about gender and feminism. Her story reveals a history of women’s struggles and of representing their issues. This insight into feminism in the past is relevant and important for new generations, to remind them that these battles were staunchly fought—and not yet won.

Sue Ford is on display at The Ian Potter Centre at the National Gallery of Victoria until August 24. Details here.