The British home secretary, Theresa May, has met her French counterpart Bernard Cazeneuve to sign a new agreement between the two countries to address the situation in Calais, where a makeshift camp known as the New Jungle is currently home to around 3,000 men, women and children seeking safety and a better life in the UK.

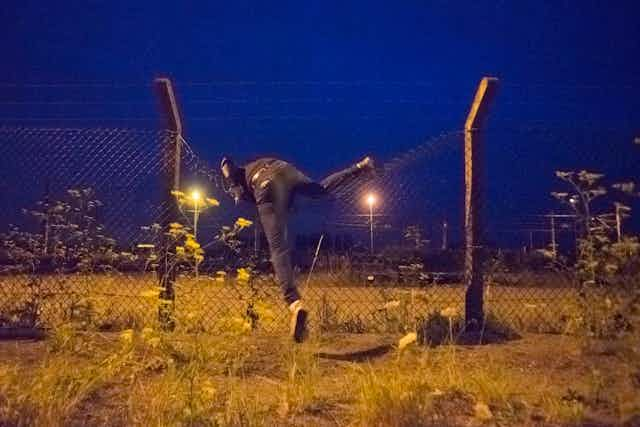

The deal focuses almost exclusively on increasing security at the UK-French border, rather than helping the people living in makeshift tents in Calais. There are already two miles of high-security fencing to keep them from boarding lorries travelling through the Channel Tunnel but that does not seem to be enough.

Now the UK plans to buy more fencing, CCTV, flood lighting and infrared detection technology to secure the area. There will be a new “control and command centre” run jointly by British and French police that will “relentlessly pursue” people-smuggling gangs. An extra 500 police will be deployed including additional sniffer dogs to hunt down those described by the British prime minister David Cameron as a “swarm” trying to “break in to” the UK illegally.

According to a six-page joint declaration, UK Border Force officers will visit migrant camps to “correct any misapprehensions” about life in the UK and to provide a “more dissuasive and realistic sense of life for illegal migrants” entering the country. And there will be a push to “maximise the number of illegal migrants who return home” although it is not clear exactly how these people will be identified or where “home” might be.

The ‘crisis’ in Calais

It all reminds me of the Sangatte refugee crisis which dominated the media during the summer of 2002. At that time I was working at the Home Office and saw politicians scurrying around desperately in search of a solution in the face of endless newspaper stories about people trying to break into the tunnel from a base in Sangatte – where the tunnel’s cooling station is located. Then, as now, media and public anxiety seemed to drive the policy response.

Eventually, David Blunkett, the home secretary at the time, agreed to give work permits to 1,000 Iraqi Kurds and indefinite leave to 200 Afghans with close family connections in the UK. In return, his French counterpart Nicolas Sarkozy would ensure the Sangatte camp was closed.

But times have changed. Over the past decade, public hostility towards refugees has grown. A recent poll found that nearly half of Britons do not think that those seeking safety from conflict or persecution should be welcomed in the UK, including those fleeing the current conflict in Syria.

According to the UN more than 4m people have fled to Syria’s immediate neighbours Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq and a further 6.5 million are internally displaced within Syria. Last year just 138,000 Syrians made it to Europe. European countries have pledged to resettle a further 33,000 Syrian refugees. The UK has offered shelter to just 187 of them.

British politicians seem happy to ignore this context. The view seems to be that everyone displaced by conflict and poverty is heading for the UK. In reality only a few thousand migrants have reached Calais. That’s about 1% of the more than 200,000 people who have landed in Italy and Greece so far this year.

Germany is expected to receive 800,000 asylum seekers this year – about four times the number it took last year and more than the total number received by all the other EU member states in 2014. Yet its politicians remain pragmatic. Commenting on the 800,000 projection Germany’s interior minister, Thomas de Maiziere said: “I don’t think this will overwhelm Germany. We can handle this.”

Self-absorbed

Propelled by a centre-right political agenda and a sense of its own self-importance, the UK appears to be working on the assumption that migrants are hell-bent on reaching the UK to exploit its benefits, jobs and a “soft-touch” asylum system.

Announcing plans to withdraw even basic levels of support for asylum seekers with children whose claims are refused, immigration minister James Brokenshire said this was to convey the message that the streets of the UK are not paved with gold, that this is not a “land of milk and honey”.

These assumptions go against all the evidence about why refugees risk everything to make the journey to Europe and why, when they arrive, a small proportion seeks protection in the UK rather than another EU member state.

In nearly 25 years of research on international migration I have yet to meet an asylum seeker – or even an economic migrant – who wanted to come to the UK to claim benefits. The decision to leave a country is almost always more compelling than the choice about where to go. For most people fleeing persecution, the primary objective is to reach a place of safety. Many have little or no choice about where that place might be.

But having lost everything (job, home, family, friends) those who have sufficient financial and social resources hope ultimately to move to the place in which they can most easily rebuild their lives. And because existing social networks and connections have been disrupted by increasingly restrictive immigration regimes, they are forced to turn to agents and people smugglers who can help them to reach countries in which they speak the same language or have close family members who can help them to resettle, albeit at a cost.

All of this means that the deal signed in Calais yesterday is unlikely to be effective. Indeed May herself acknowledged that increased controls will probably only shift the migrants from Calais to other ports.

Remembering humanity

Just as importantly, focusing on controlling those who are forced to move rather than protecting them dehumanises people who are seeking safety and a better life for themselves and their families. It takes us one step closer to what we saw in Europe in the run-up to World War II.

Across Europe, metaphorical and concrete walls are being built to keep out those who have nowhere else to go. In Hungary a fence built by prison inmates will stretch across the length of country’s border with Serbia to prevent migrants entering from the Balkans. In Slovakia, the government has announced that it will resettle 200 Syrian refugees but those refugees have to be Christian.

During May’s visit to Calais, Cazeneuve said asylum seekers should be welcomed “with dignity” but that illegal immigrants would not be tolerated. Given that there are no legal entry routes for anyone who arrives in Calais it remains unclear how this distinction will be made.

Meanwhile dignity also appears to be in short supply. When people gathered at the New Jungle to protest against the measures they were dispersed by police using tear gas and batons. “We are humans, not animals” they cried. British and French politicians would do well to remember that.