Beyond the viral contagion of COVID-19, the pandemic’s accompanying social and economic hardships have challenged many people’s physical and mental wellness. Over the past year of navigating living in a pandemic, it’s become clear that relationships matter to health: relationships between body and mind, between neighbours and between individuals and their societies.

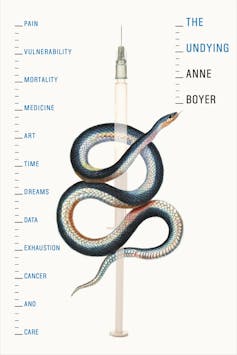

Literature was dissecting these connections long before the outbreak. Recent memoirs, non-fiction, fiction, poetry and graphic novels related to physical and mental health examine not just the fragility of individuals but how individuals relate to social and power structures like capitalism, racism or colonialism. Writers have also explored how people’s social roles and identities shape their relationships to narrative itself. As American poet and memoirist Anne Boyer writes in her Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir, The Undying, “I do not want to tell the story of cancer in the way that I have been taught to tell it.”

For several years, I have been researching, writing about and teaching literary texts related to maladies like depression, substance abuse and cancer. I’m interested in how narratives about health published today explore the interdependence of bodies and their environments in a way that may teach us important lessons during the pandemic, and beyond it.

The ‘literature of madness’

Since the 1960s, critiques of medical education, medical ethics and the role of narrative in healing have meant an emerging awareness of how the medical field can be allied with literature.

Some medical schools are requiring students to take literature courses to become more adept with reading patients’ stories; some students take my contemporary literature course at University of Victoria to satisfy a medical school course requirement. The convergence of these two fields is helping to disrupt the canonical “literature of madness.”

Starting in the 1970s, mental illness became a hot topic in literature departments. Books like Shoshana Felman’s Writing and Madness and Lillian Feder’s Madness in Literature marked the new interest.

In “Literature of Madness” courses at various universities, students studied Dostoyevsky’s The Double, Charlotte Perkin Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Ken Kesey’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar.

These health stories pit mentally ill characters against individual antagonists like husbands, mothers, doctors and nurses, or, fighting oneself as seen through the ancient literary theme of the double or dopplegänger (as in Dostoyevsky’s tale). Yet some critics have also explored how these narratives examine individuals battling formidable but intangible foes, and thus comment on social ills: For example, patriarchy in The Bell Jar and “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

Social ills

Many recent health narratives today are questioning how well-being is damaged by social determinants of health like income inequality and racism. They are also examining how health relates to phenomena like capitalism and climate change, which are elusive but all-pervasive.

For instance, Boyer damns the American health-care system, with its outrageous costs and lack of guaranteed sick leave, but also capitalism as a whole. For her, like Susan Sontag, cancer infuses culture as much as human bodies, but economic pressures also cast a huge shadow.

Blending personal experience and big-picture analysis can be found in other recent health memoirs. In The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath, American writer Leslie Jamison discusses her own experiences of alcoholism as a white woman alongside the racism of the American criminal justice system. As she observes: “White addicts get their suffering witnessed. Addicts of colour get punished.”

The best-selling essay collection A Mind Spread Out on the Ground, by Tuscarora writer Alicia Elliott, examines how systematic oppression of Indigenous communities is linked to depression. Her settler therapist can’t understand why she’s depressed, and none of her self-help books actually help.

She writes of one, “There is nothing in the book about the importance of culture, nothing about intergenerational trauma, racism, sexism, colonialism, homophobia, transphobia.”

This interest in the social determinants of health isn’t limited to non-fiction. Sabrina by American cartoonist Nick Drnaso is a 2018 graphic novel that was longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker Prize. Sabrina takes stock of what appears to be PTSD and depression in a political climate of misinformation and conspiracy theories.

As one character fills out a daily wellness report, the reader may realize anyone would feel depression and anxiety in such a world.

Health among the living

Meanwhile, Fady Joudah, a Palestinian American poet and practising doctor, weighs economic inequity and a lack of sustainability in “Corona Radiata,” a poem about COVID-19 published last March. “Corona Radiata” argues that we need to understand health as contingent on relationships between humans — and between humans and other living things. Joudah suggests that:

“Far and near the virus awakens

in us a responsibility

to others who will not die

our deaths, nor we theirs,

though we might …”

He’s right, if hopeful. Until the vaccine is widely distributed, public health will depend on our ability to understand ourselves as part of an inconceivably vast network.

American novelist Richard Powers’s The Overstory, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2019, also unites health with responsibility. In the novel, characters challenged by physical disabilities and strokes find ways to communicate with and through nature. A scientist almost dies by suicide early in the novel before recommitting herself to loving as well as studying the trees. Environmental activism gives them purpose, even if it doesn’t heal them.

Future health stories

British writer Robert Macfarlane has proposed that the environmental crisis will continue to transform our literature and art. Many recent works support his idea. In particular, the latest health literature fuses various genres, including memoir, biography, reportage, literary and cultural criticism, science writing and prose poetry.

The new health literature also reminds us that our health and the planet’s are inextricably linked. In the near future, this genre is likely to increasingly address the impact of climate change on our physical and mental well-being, such as the rise in eco-anxiety. I think we’ll see a blending of literature, medicine and environmental studies more and more often.

Some researchers have noted a link between reading and longevity in individuals. Reading health literature may spur us to support longevity for the Earth too.