In the week following the release of Still Alice, the Oscar-winning film about early onset Alzheimer’s, the disease has again made headlines with the story of Chris Graham, a former soldier who has the disease and is already showing symptoms age 39. He is planning a year long 16,000 mile cycle ride to raise money for Alzheimer’s Research UK. June Andrews recently argued in The Conversation that the film is far from a good thing for raising dementia awareness. But in the context of stories like that of Graham, I believe that for all its flaws, Still Alice is commendable: it tells a story that is worth telling.

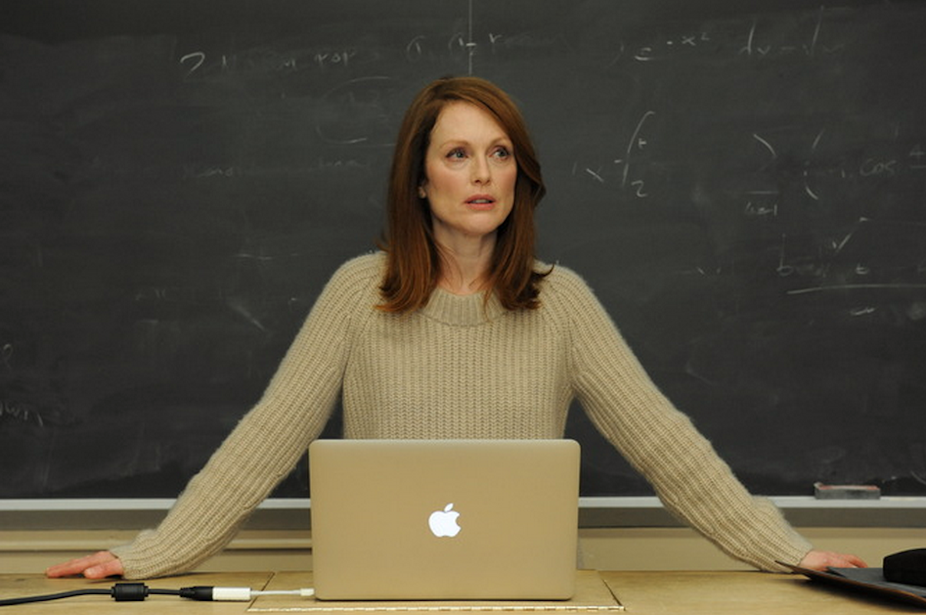

The film is the fictional tale of Alice Howland, an esteemed 50-year-old US linguistics professor, long and happily married to a senior research physician. They have three adult children; a medic, lawyer and a struggling thespian. When giving a lecture, the word “lexicon”, a linguist’s cornerstone, eludes Alice; later a familiar run becomes a nightmarish fog of formless space, shapes and shadows. A rare hereditary type of Alzheimer’s disease is diagnosed and testing reveals a genetic passing on to the elder, pregnant daughter.

An aggressive disease trajectory then robs Alice of her own metaphorical “lexicon”, her inventory of herself in relation to people, places, objects and happenings. Technology helps for a while; lists, reminders and word games, the setting up of a doomed, future suicide plot. At an Alzheimer’s conference Alice speaks of struggling, not suffering. She asks how others can now take her seriously when she is so far removed from who she used to be, the Alice who “was” an articulate, intelligent wordsmith. She says cancer would be better than being the Alice she has become, a shameful, erratic, comic version of herself. She emphatically declares: “This is not Alice … This is the disease.”

Julianne Moore’s performance as this arresting, fading and faded Alice deeply unsettles our notions of biography, of our past and future selves. But despite this degeneration, this constant change of sense of self, life is still lived. This is humorously illustrated by younger daughter Lydia who forgives Alice’s intrusive reading of a personal journal because the Alice of the following day will have no memory of yesterday’s transgressive Alice. And this irony of “gone” selves is a shared joke between the two that’s not lost on Alice, for that moment at least.

Articulating these little ironies and quiet moments for the cinema is a real feat. And so despite being a little irritated by the shine and prettiness of this film, it has a place in increasing awareness of the disease. Yes, it’s true that the film fails to engage with much more common tales of living with less rare, wide ranging, dementias in our 70s, 80s and beyond, but we need both of these and more to be explored, and in any way that people will engage with it.

The wider picture

In the UK some 40,000 people under 65 have early onset dementia, 5% of all diagnosed cases. So the dementias, including Alzheimer’s disease, are largely diseases of older people. But equally, early onset dementia and its impact on paid work, dependents and others, can be hidden, misunderstood and ill served. Still Alice gets us talking, about this form of the disease, and others. We need the arts and media to open up such public conversations – it is a role they have long played and must continue to do so.

Of course we need to think carefully how this is achieved. As Andrews says, artists and the media in general may feed off current anxieties about dementia. A recent study of media reporting of the disease condemns the catastrophic language often used, such as “ticking time bomb”.

Yet the media and arts have also given us rich history of intelligent documentary and fictionalised film on early onset dementia. There was the 1996 short documentary Forget Me Never. And Rachel Stace and Rebecca Mellor’s 2002 film Stolen Memories, documented ten months in the lives of three people in their 50s living with Alzheimer’s disease. The 2006 Japanese film Memories of Tomorrow, about a 49-year-old man with Alzheimer’s disease. And Paul Watson’s film won a BAFTA award for documenting 14 years of a couple’s life after one of them was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s at 51.

All these and more have contributed to a growing conversation about the disease, which Still Alice is perhaps the first really public airing of. You need debate, good and bad, to keep the conversation alive.

I am not an expert in dementia but I am a profound believer in the potential good of the arts and media to keep us talking, questioning, challenging. With colleagues I have worked with talented companies such as Skimstone Arts, and artists like Romi Jones and others, to use theatre, film and creative writing to share research findings about living with dementia.

So Still Alice adds to what has gone before it. I found myself thinking anew about separating out the disease from the person. Ultimately, Alice is still Alice. And that’s worth another conversation.