With IVF success rates in the spotlight, patients are worried. They don’t want to wind up like Victorian couple Sarah and James Leury who spent nearly A$100,000 on 12 cycles of IVF (in-vitro fertilisation) over five years.

After ten cycles, the Leurys switched clinics – from one that doesn’t disclose its success rate to a clinic that claims to be one of Australia’s best – and became pregnant after two more tries.

The problem is, clinics aren’t compelled to disclose their success rates, so it’s impossible to compare all clinics. Even when they do, the pretty graphs on clinic websites can be difficult to understand.

So how can you make sure you don’t end up in the same boat as Sarah and James? Well, keep reading for a scientist’s perspective on the key factors that influence IVF success and some tips for asking the right questions.

1. Pregnancy versus live birth rates

Unfortunately, along with fertility, IVF success rates decline as women get older. Across all clinics, the highest success rates are for women under 30, who have around a 26% chance of taking home a baby after each fresh cycle. Women over 40 only have around a 6% chance.

If that’s not bad enough, only 50% of “clinical pregnancies” for women in the over-40 age bracket will result in a “live birth”.

So when you look at clinic websites and you see the “pregnancy rate” displayed as opposed to the “live birth rate”, take note, especially if you’re over 40. While the industry may view pregnancy rates as a marker of success, the women who lost their babies may not.

Prospective patients should ask their clinic to disclose both the pregnancy and the live birth success rates for their age group. While there is no obligation to provide this information, it may reflect poorly on their service if they refuse.

2. Blastocyst cultures

Another predictor of success is whether blastocyst culture is used.

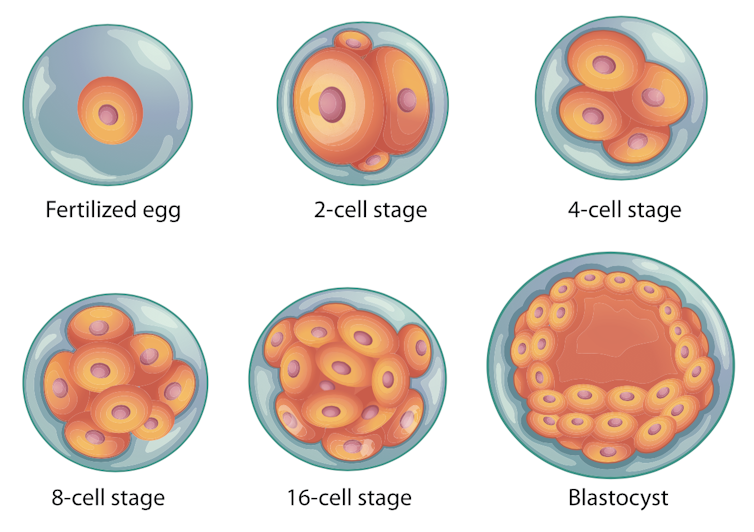

Traditionally, embryos were grown for only a few days until the “cleavage” stage. Nowadays, the aim of most treatment is to grow embryos for five days or until they make it into a blastocyst.

It’s like The Hunger Games for embryos; the best survive to the end and the weaker ones die off. This selection process makes it easier for embryologists to choose the best embryo for transfer, which, in turn, improves results.

But blastocyst culture can make some patients nervous. They don’t like the idea of scientists in the lab playing survival of the fittest with their future offspring.

Some also remain concerned that the lab doesn’t resemble the natural conditions closely enough and that some of the “weaker” embryos that are culled could have resulted in successful pregnancies.

While these concerns are understandable, there’s no scientific evidence that anyone’s “throwing the babies out with the bathwater”.

Blastocyst culture is generally recommended if you get a decent number of eggs. If you culture embryos only to the cleavage stage, you have less chance of success because it’s harder to pick the best one. Any excess “weaker” embryos get frozen along with the good ones. When you come to thaw them out, you don’t know which one you’re going to get. This also means you can end up spending thousands more on thaw cycles than you otherwise would have.

At the end of the day, it’s a personal preference, but buyer beware!

Also, be mindful that some clinics only show success rates for blastocyst transfers. If this is case, you should ask your clinic for their cleavage stage success rates too.

3. Sperm injections

The cause of infertility also plays a role in IVF success. Some male partners, for example, have a low sperm count and need intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). This is where an individual sperm is injected into an egg.

Belgian Professor Andre Van Steirteghem, one of the pioneers of ICSI, thinks ICSI is overused. But patients risk having a failed fertilisation if they don’t use it. And with severe male factor infertility, donor sperm may be the only alternative.

Sometimes, when it’s unclear if a patient needs ICSI, the doctor will allow half of their eggs to be inseminated via standard insemination and half to be injected via ICSI. If you get enough eggs, this is something worth enquiring about.

4. Budget clinics

Using budget IVF clinics can also affect success. These have been described as “cheap and nasty” by some in the industry but that’s certainly not the case. You just need to know what you’re getting into.

Basically, budget clinics use low-dose hormone stimulation protocols so patients spend less on the drugs. But it’s generally only suited to younger patients. It also produces fewer eggs. This means fewer resources are required to perform lab procedures and that’s probably the real reason it’s so cheap.

In budget IVF, doctors aim to get about seven to ten eggs per patient. If the patient responds well, this number is fine. But that’s not always the result. If you get only a couple of eggs, you need to be aware you may not get an embryo for transfer or anything to freeze. Then you’ll have to start again.

Budget IVF patients should ask their clinic how they plan to monitor their response to the low dose. If you get a poor response it’s hardly worth the trouble.

Some people have also expressed concerns that the lab procedures in the budget clinics might be different from in the more established ones. Clinics generally claim they’re the same but it’s definitely worth enquiring about. There shouldn’t be any shortcuts, or hidden extras.

5. Lab standards

There’s also more than just biology involved in IVF. Embryos are highly sensitive to things such as changes in temperature and oxygen levels. These conditions need to be monitored tightly as their effect on success rates can be catastrophic.

Some embryologists have privately questioned whether different standards in laboratory quality might be one of the reasons for cases such as the Leurys’. It can cost a lot to get things right.

In Britain, clinics are required to publicly release their inspection reports. Australia should introduce this too.

In the meantime, patients should ask what steps their clinic takes to ensure their embryos are being looked after in the lab.

There are just so many things patients have to think about before embarking on IVF, and not all of them were talked about here. The most important point is that patients go in prepared and ask lots of questions as each clinic does things a little differently.

Knowledge is power, and IVF is expensive. While it’s awful to think of your future children as a transaction, modern IVF really is a case of buyer beware.