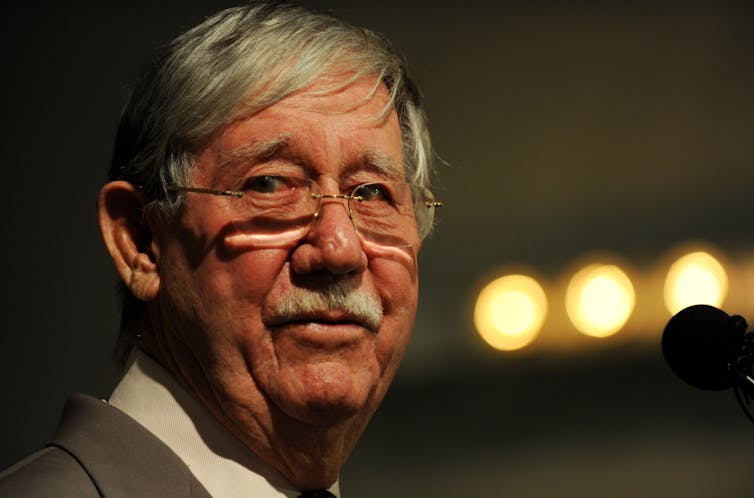

Reg Grundy, who has died in Bermuda at age 92, did for television content what Henry Ford did for car production. He saw the potential to take a story-line with a strong emotional centre – of proven appeal in one market – and produce it, with small cultural variations, to capture the interests of audiences in countries around the world. It was production to a strict format.

Grundy – the TV mogul who never owned a TV station – pioneered the idea of the format as the core of a program and a saleable commodity. A format is a generic version of a TV show: for instance, a drama centred around a specific socio-economic setting with particular characters and narratives. The key with formats is that it’s the emotional core of the show that matters, not the cast or location.

Here are five ways he changed Australian TV:

1. Turning radio game shows into TV fodder

Grundy started in radio as a quiz master and developed the radio game show Wheel of Fortune. In 1959, he adapted the format for TV and sold it to Channel 9. Wheel of Fortune remains popular in the USA. This was the beginning of a long, but not exclusive relationship with the Packer empire.

2. Making local versions of US shows

Grundy quickly realised that early Australian television was a potential market not just for US programs, but for local adaptations of US shows. He brought the US game shows Concentration and Tic, Tac, Dough to Australia, the latter’s format copied from NBC in the US. Over the next decade, other game shows such as I’ve Got a Secret and Play Your Hunch followed, gaining large and faithful local audiences. In due course, he started producing local versions of foreign formats in the US too.

3. Making iconic drama

Grundy expanded into drama following the success of Crawford Productions in Melbourne, but with a distinctly more tabloid approach. (Or perhaps, that was just the Sydney sensibility, pioneered by Number 96.)

Prisoner (still in production here on Pay TV as Wentworth) was an early success, and was followed by soapies like The Restless Years and The Young Doctors. Then came Sons and Daughters, a show that ran to 972 half hour episodes.

And Grundy was tenacious with his titles, not abandoning one if rejected by a TV station. Such was the case with Neighbours. Rejected by ATN Channel 7 after one season in 1985, Grundy sold the program to Ten the following year, and then to the BBC, where it achieved popularity to rival Coronation Street and adopted some UK story lines. Neighbours has gone through a dozen casts and hundreds of script writers but remains Neighbours to this day.

4. Seeing new business opportunities

Grundy developed the trade in formats in ways not then pursued by production companies. He recognised that underlying the scripts of a successful series lay some core concepts that made the production unique. These format elements, as well as the scripts, were saleable commodities.

Grundy would take the key elements of the story – the characters and the relationships, as well as the scripts – and on sell them to another country to be adapted to their market. Sons and Daughters, for instance, is still selling as a format almost 30 years after it first appeared in Australia on Channel Seven. Recently, it was remade as Zabranjena Ljubav in Croatia and, separately, in Bulgaria, under the same title.

Under format licensing agreements, the remakes normally vary little from the original production, but are given tweaks for local cultural sensitivities and technical and production limitations. This rigidity preserves the value of the brand but also gives confidence to advertisers that the program’s commercial performance is likely to match the performance of the original.

5. Knowing when to call it quits

Grundy knew when to hold, and when to fold. If you are working in global market, it is a valuable lesson for small players in Australia to take note of.

In 1995, Grundy sold to the UK conglomerate Pearson Television, now known as Fremantle Media. Its Australian arm remains a prolific television producer and distributor of programs.

Formats, however, are largely oriented towards the tabloid end of television. They support a production line approach to content creation. Given the voracious nature of broadcast, online and on-demand television, such productions fill hours of television each day.

Still, they do no replace flagship production for prime time, where audiences still hunger for the new, the innovative and, sometimes, the demanding and controversial.

Alongside the cookie-cutter format remakes, there will always be a place for excellence in TV production.