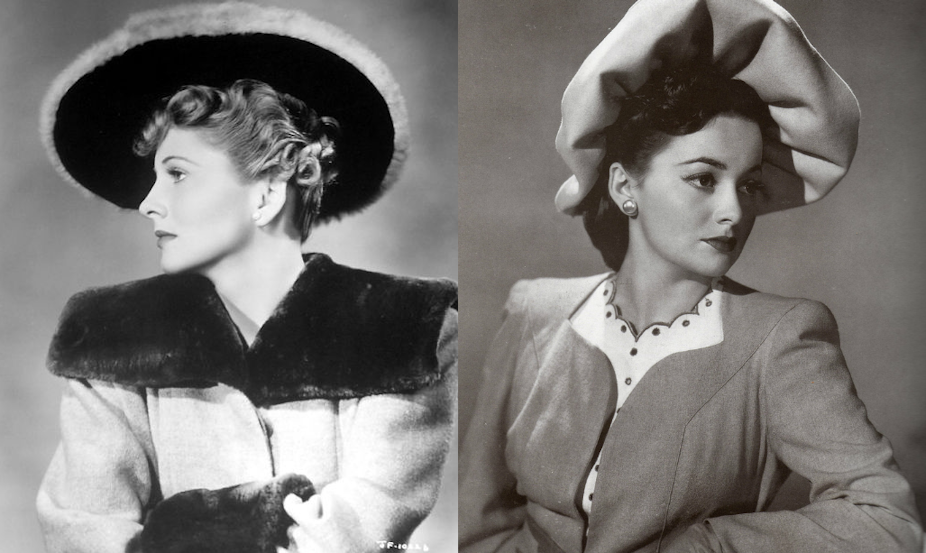

Movie lovers mourned the sad death of the Oscar-winning actress Joan Fontaine this week, one of Hollywood’s golden stars. A recurring theme in her obituaries was her very poor relationship with her older sister, fellow Oscar-winning actress Olivia de Havilland.

It was reported that the two sisters didn’t really speak to each other for much of 40 years and it was one of Tinseltown’s most bitter and longest-running feuds.

It might be expected that two sisters would be close. Two sisters who were both actresses of acclaim might be expected to be even closer. But perhaps that holds the clue to the source of the hostility.

The famous sisters are, of course, not the first victims of sibling rivalry.

In the Bible, Cain killed Abel out of jealousy for what he believed to be God’s preference for his brother. Temujin – who grew up to become Ghengis Khan – killed his half-brother in a fight over food. And in Shakespeare’s King Lear, the old king deliberately provokes his three daughters to compete with each other.

More recently, we’ve seen the intense rivalry between the journalists Christopher and Peter Hitchens, and in UK politics between Ed and David Miliband.

You don’t have to be a professional psychologist to see sibling rivalry – parents see it every day. But what can start as quite a normal reaction can get out of hand or trigger a feud in later life (as appeared to happen in the Miliband’s case). Aggravating factors might include personality differences, gender distribution, size of the family and age gap.

Compete or co-operate?

I am not a big fan of Freudian theory. And it’s rather reassuring to see that the most common psychological explanations for sibling rivalry are quite straightforward. Basic evolutionary theories would suggest that we are all in a constant tension between co-operation – because through co-operation we all succeed together – and competition.

Within families we must work with our siblings, but we are also compelled to compete with them. For Ghengis Khan, the competition was acute; he fought with his half-brother for food in a brutal struggle for survival. In modern, more materially secure, families, children compete first for the attention of their parents.

For the first child, the arrival of a younger rival for their mother’s attention can occasionally be difficult.

And mothers will always find it difficult to offer as much attentive care to two children as one, and the younger more vulnerable child often takes priority.

It’s therefore very tempting for children to compete for attention. And of course there can be many ways in which parents can either help to reduce, or occasionally unwittingly encourage this rivalry.

People can be very complex, but we can also be quite simplistic sometimes. And that includes limited imaginations. We should, of course, co-operate with the people closest to us (especially when they share our genes). But it also makes sense to compete with the people closest to us. So instead we compete with the people we see every day. We look back at classmates from school to work out who has made the most out of life; we compare our success – or earning power – with our peers and colleagues.

It’s mildly alarming when you’re the same age as the prime minister – that’s when comparisons start to become more acute.

Winning your own competition

Within families, it’s for our mothers’ and fathers’ attention. In our evolutionary past (and in the current reality for many people) we competed for scarce resources or food. And this sets us up for all kinds of tests and competitions, much to the frustration of parents who would prefer a more harmonious household.

De Havilland, a keen mind, was said to have set up a competition as the editor of a school magazine to find the best last will and testament by fellow pupils. She won her own competition for writing about Fontaine: “I bequeath to my sister the ability to win boys’ hearts, which she does not have at present”. Not the most diplomatic approach.

In a rational world, there are billions of people that I could compare myself with. But I’m always most likely to compare myself with my classmates, school friends, my parents and, most importantly, my siblings. We should perhaps have wider perspectives, but our evolutionary history, our childhoods, our psychological make-up all conspire against us.

It’s a little like being in a long-distance race; it’s understandable to set our eyes on the athlete just in front of us. We try to gain on them; we try not to lose ground. Perhaps we should think about our personal best time, or target the leading group. But a great many of us set our eyes on the person just in front.

Fontaine herself summed this up. The similarities between her and her still surviving sister perhaps fostered more competition that was needed to make them happy with each other. In an interview in 1978 she said: “I married first, won the Oscar before Olivia did, and if I die first, she’ll undoubtedly be livid because I beat her to it!”. In a rare public statement, the 97-year-old de Havilland said she was in mourning for her sister who she would never forget. After all these years, perhaps the feud will now be laid to rest.