According to experts, today’s global agriculture system faces a crisis. Intensive farming with heavy ploughing machinery is causing soil to be lost up to 100 times faster than it is formed – and valuable stored carbon with it too. The soil that remains is becoming depleted of nutrients, thanks to repeated cultivation of the same staple crops without respite.

To delay the consequences of this “cereal abuse” and soup up crop yields, farmers artificially fertilise soils with synthetic nitrogen, typically made using natural gas or coal. This, combined with methane released by cattle and the loss of stored carbon from deforestation for agriculture, means that a quarter of all planet-heating gases come from how we feed the world. These gases are bringing weather patterns so extreme that some experts believe multiple crop failures and food system collapse could be a possibility in as little as a decade.

Agriculture is eroding wildlife too. Run-off of fertilisers is causing dead zones in downstream rivers and oceans. Pesticides and the conversion of wild habitats to farmland are harming the insects that pollinate crops, and the plants they rely on to thrive.

To top it all off, by the middle of the century there are expected to be a quarter more mouths on the planet to feed. By that point, the global food system is predicted to cause the planet to exceed key environmental limits that define a safe operating space for humanity.

The future of food, then, may sound rather bleak. But it doesn’t have to be this way. With drastic changes, the food system could help solve environmental challenges and support human wellbeing.

The question is how to bring about this future – and there are some radically different suggestions out there. In this sixth issue of Imagine, academic experts explore the competing visions on offer, and assess what needs to be done to create a food system that feeds the world and heals it too.

The “green revolution” that produced a fourfold increase in global food production since the middle of the 20th century relied on pesticides, fertilisers, machinery, and monocultures. What should the next agricultural revolution hold?

What is Imagine?

Imagine is a newsletter from The Conversation that presents a vision of a world acting on climate change. Drawing on the collective wisdom of academics in fields from anthropology and zoology to technology and psychology, it investigates the many ways life on Earth could be made fairer and more fulfilling by taking radical action on climate change.

You are currently reading the web version of the newsletter. Here’s the more elegant email-optimised version subscribers receive. To get Imagine delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe now.

We can hack photosynthesis

According to some, a technological revolution that could solve the food crisis is already underway. In this imagined future, next generation biotechnologies will re-engineer plants and animals. Global food systems will rely on smart robots, blockchain technology and the Internet of Things to manufacture synthetic foods for personalised nutrition. Nanotechnology will maximise the efficiency of fertilisers and pesticides, and improve gene-editing to create crops resistant to the impacts of extreme weather.

One techno-fix in particular lights up the night sky with a bright pink glow: vertical farms. They use high-tech lighting and carefully control the indoor climate to bypass the constraints of Earth’s natural cycles to grow crops 24 hours a day, all year round.

Because they recycle water that evaporates from the plants, these closed systems use as little as one-twentieth the water of traditional farms. Most don’t need soil either, because they dispense nutrients via mist or water.

They’re at much lower risk of crop loss from contamination, pests, and storms, too. And because they can be placed on unproductive and urban land, they can decrease food miles and provide local produce to city dwellers.

According to expert in food security Asaf Tzachor, they can even help save rainforests. He went to investigate a cutting-edge indoor farm project in Iceland’s Hellisheidi geothermal park. It closely regulates temperature, lighting, nutrient concentrations, and harvest timing to grow not crops, but plant microorganisms.

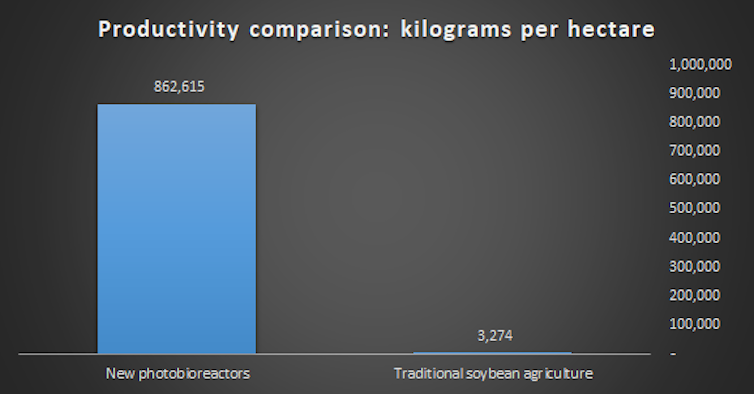

Using this technique, the project’s photo-bioreactors can produce microalgae with similar nutritional content to soybeans at less than 0.6% of the land and water use.

This is important because soy cultivation for animal feed is a leading cause of deforestation in the Amazon basin. And thanks to projected rapid growth in both world population and in the meat-eating global middle class, demand for soybean is set to grow 80% by 2050 – more than any other staple crop.

Read more: How hacking photosynthesis could fight deforestation and famine

Is technology the saviour, really?

The trouble is that these technologies often require vast amounts of energy and resources to produce and maintain. As sustainable design researcher at Queen’s University Belfast Andrew Jenkins argues, why ramp up power demand at a time of climate crisis, only to replace what the Sun gives us for free?

Read more: Food security: vertical farming sounds fantastic until you consider its energy use

For agricultural ecologist Michel Pimbert and food systems expert Colin Anderson, both at Coventry University, there are deeper problems with a high-tech agricultural future. They argue that it would:

reinforce the concentration of political and economic power in the hands of a small number of corporations, such as the World Economic Forum’s “Transformative Twelve”; technologies that intend to redesign food systems, but are already under growing monopoly control

further increase the role that financial markets play in controlling food systems, risking the repeat of earlier food crises

result in an increasingly nature-less and people-less food system. As they put it:

Flying robots will pollinate crops instead of living bees. Automated machines will replace farmers’ work on soil preparation, seeding, weeding, fertility, pest control and harvesting of crops.

Read more: The battle for the future of farming: what you need to know

Agroecology: because nature knows best

Rather than filling the gaps humans have created in the biosphere with technology, Pimbert and Anderson suggest that the biosphere itself can help solve the food crisis.

Read more: Techno-fix futures will only accelerate climate chaos – don't believe the hype

Agroecology – a system of farming that uses or mimics natural interactions between organisms and their environments – has been highlighted as the most promising pathway to sustainable food by several UN reports. According to Karen Rial-Lovera, a senior lecturer in agriculture at Nottingham Trent University, agroecologists promotes circular systems for growing food that:

improve soil quality by planting nutrient-fixing “cover crops” in between harvest crops, rotating crops across fields each season, and composting organic waste – often including human manure

support wildlife, store carbon, and conserve water through the planting of trees and wildflower banks

control pests and diseases by harnessing natural repellents and traps. Peppermint, for example, disgusts the flea beetle, a scourge to oilseed rape farmers.

Read more: Three ways farms of the future can feed the planet and heal it too

As Pimbert and Anderson explain, agroecology can also help break monopoly power over food systems and return control over the way food is produced, traded and consumed to communities. The system’s short food chains and local markets reduce the dependence of farmers on expensive external inputs, distant commodity markets and patented technologies.

Research and innovations in agroecology are also being driven largely from the bottom up by civil society, social movements and allied researchers. Pimbert and Anderson argue that this offers hope that the system can regenerate not just local ecologies, but local economies and livelihoods too, increasing the income, working conditions, skills and political capital of small-scale farmers. They believe that, compared to technology-dependent visions of agriculture, it’s much more likely to nourish communities in a fair, ecologically regenerative, and culturally rich way.

Millennia of trial and error

Many agroecological practices are nothing new. As Anna Krzywoszynska – associate director of the University of Sheffield’s Institute for Sustainable Food – explains, while limited soil fertility can now be bypassed with fossil fuel-derived fertilisers, for most of human history, using the local environment and labour to maintain soils in a good state was key to survival.

Read more: IPCC's land report shows the problem with farming based around oil, not soil

There are plenty of success stories from ancient civilisations that managed to do just that with rather simple means. Kelly Reed, an archaeobotanist at the University of Oxford, thinks we could learn a thing or two from them when building a sustainable future for food. She shares how in southern China, farmers add fish to their rice paddy fields in a method that dates back 2,000 years.

The fish are an additional protein source, so the system produces more food than rice farming alone. They also provide a natural pest control by eating weeds and harmful pests such as the rice planthopper. Compared to fields that only grow rice, rice-fish farming increases rice yields by up to 20%, while using less of the agricultural chemicals that pollute water and generate greenhouse gases.

But according to Reed this practice, like many others with ancient history, is a dying art. Today, smallholder rice-fish paddies are increasingly being pushed out by larger commercial organisations wishing to expand monoculture rice or fish farms.

Power to the producers

But research suggests it’s not too late to reorient farms around age-old wisdom and natural solutions. At least 75% of the world’s 1.5 billion smallholder farmers still practise agroecological techniques today.

Most of these are in emerging economies such as Brazil, India, China and South Africa – countries in which industrial agriculture also occupies a growing share of land. Boosting small-scale farming is particularly important for such countries, say University of Cape Town’s Rachel Wynberg and Stellenbosch University’s Laura Pereira, both experts in agricultural transformations.

They argue that these emerging economies could and should invest heavily in agroecological research and training programmes, especially where resources are scarce. If they do, they could avoid having to depend on technology and monopolies for food security, improve the livelihoods of small-scale, resource-poor and often marginalised farmers, and address the environmental damage wrought by industrial agriculture at the same time.

Read more: Why developing countries should boost the ways of small-scale farming

Carbon farming

Nature-inspired agriculture can also play an important role in tackling the climate crisis – and not just from using less fertiliser.

Healthy peatlands contain more carbon than all the world’s vegetation combined, but the vast majority of them throughout Europe and much of the world have been drained and converted into farm fields. The drained peat soils that stand in their place emit vast quantities of carbon dioxide – the total emitted each year from just the UK’s East Anglian Fens and damaged upland peat soils may be equivalent to around 30% of the country’s annual car emissions.

This widespread draining is largely owed to the fact that our agricultural system spread from the dry semi-desert conditions of the Middle East during the shift from hunter-gathering to settled farming. This means that farming has been dominated for the past 5,000 years by the principle that dry land is good and wet land is bad.

Peatland conservationist Richard Lindsay wants to change farming’s celebration of dryness. He says that wetlands can provide highly productive new forms of farming that not only grow crops, but also reduce the risk of floods and add to rather than deplete reservoirs of soil carbon.

In Germany, for instance, a type of “bulrush” is already being grown on wetlands and used to produce fire-resistant building board. At the University of East London, Lindsay is testing two potential crops: sphagnum bog moss as a replacement for peat in garden-centre “grow bags”, and “sweet grass” as a food crop.

Read more: Carbon farming: how agriculture can both feed people and fight climate change

In the future then, many farmers could be cultivating carbon as well as crops. Here’s a vision for what life could be like for a “carbon farmer” three or four generations from now:

Taking the carbon out of cows

It’s impossible to discuss farming and the climate crisis without mentioning animal agriculture. The livestock industry alone accounts for about 15% of global emissions. But, according to Rial-Lovera, that doesn’t mean it should be done away with entirely.

Rial-Lovera outlines how carefully managed grazing can actually help the environment, not harm it. Grassland captures carbon dioxide. Animals eat the grass, and then return that carbon to the soil as excrement. The nutrients in the excrement and the continuous grazing of grass both help new grass roots to grow, increasing the capacity of the land to capture carbon.

Keep too many grazing animals in one place for too long and they eat too much grass and produce too much excrement for the soil to absorb, meaning carbon is lost to the atmosphere. But if small numbers are constantly rotated into different fields, the soil can store enough extra carbon to counterbalance the extra methane emitted by the digestive rumblings of livestock.

Ian Lunt – associate professor of vegetation ecology and management at Charles Sturt University in Australia – insists that livestock bring other benefits to the land too. They keep soil naturally fertilised, and can also improve biodiversity by eating more aggressively competitive plants, allowing others to grow. And if local breeds are adopted, they generally don’t require expensive feed and veterinary care, as they’re adapted to local conditions.

University of California animal biotechnologist Alison Van Eenannaam argues that this is a much more environmentally friendly way of producing meat than lab-grown equivalents. She writes:

Nature has already developed a fully functional biological fermentation bioreactor for the conversion of inedible solar-powered cellulosic material, such as grass, into high-quality protein. It is called a cow.

Read more: Why cows are getting a bad rap in lab-grown meat debate

Less grazing, more rewilding

But the global livestock population will still need to fall drastically if agriculture is to stem rather than accelerate global heating. In the UK at least, this transition can bring multiple environmental benefits without compromising the livelihoods of livestock farmers, says the University of St Andrews’ Ian Boyd.

Around 20% of the UK’s farms account for 80% of the country’s total food production, and they do this on about half of all the farmed land there is. At least 80% of farms in the UK don’t produce very much at all, and rely heavily on government subsidies to stay viable. Livestock farms are the least profitable of all, yet they take up 45% of the UK’s land surface.

Instead of propping up unproductive crop and grazing land, subsidies could instead task farmers with rewilding their land to forest or other habitats that can lock away CO₂ and expand habitats for wildlife, says Boyd. Farmers could also be rewarded for opening land near urban areas for public access, creating places of recreation that support human wellbeing.

This would free up not only grazing land, but vast swathes of land currently used to grow animal feed. The livestock industry is an inefficient use of land – only 10-20% of the vegetable matter fed to livestock is converted into meat. Around 75% of the calories fed to livestock in the UK comes from land that could produce human food, or be rewilded, says Boyd.

Read more: Climate crisis: the countryside could be our greatest ally – if we can reform farming

Read more: Rewild 25% of the UK for less climate change, more wildlife and a life lived closer to nature

Anything is possible

Of course, this would mean us all eating much less meat. Bringing people on board with this might seem like an impossible task. But Paul Young, associate professor of Victorian literature and culture at the University of Exeter, shows us that meat-eating habits are more malleable than we might think.

In 19th-century Britain, a fast increasing population caused a mid-Victorian “meat famine”. To stave it off, groundbreaking preservation and transportation technologies were developed that enabled the British to eat livestock reared in the Americas and Australasia. This laid the foundations for the global meat markets that support the overproduction and consumption of meat today.

Mass marketing campaigns alongside positive media coverage also helped promote these new forms of meat, until they became seen as an essential part of everyday meals for all. As a result, per capita meat consumption rose by nearly half between the 1850s and the 1910s, despite the fact that Britain’s population nearly doubled during this period.

The globalisation of Victorian meat eating was revolutionary, but it was also highly controversial. Many were wary of eating long-dead animals from far flung parts of the world. Overseas competition provoked demands to protect British agriculture, both to preserve traditional ways of life and to guarantee food security. Animal rights campaigners too were concerned at the increasingly intensive farming methods and assembly line slaughter techniques associated with developing meat markets.

Read more: The Victorians caused the meat eating crisis the world faces today – but they might help us solve it

For Young, this Victorian history shows that hundreds of millions of people eat meat in the way and the quantities they do, not because they’re inherently designed to do so, but because of a global system set in motion by British imperial power. Not so long ago, the prospect of eating frozen lamb from the other side of the world provoked scepticism and disgust. Who’s to say that we can’t transform our dietary habits once more – or the future of our food system, for that matter?

Further reading

Meat tax: why taxing sausages and bacon could save hundreds of thousands of lives every year

How gardeners are reclaiming agriculture from industry, one seed at a time