Force-feeding or starving to death? Emotive terms for an appalling choice. But this choice – whether to restrain and force-feed a young woman against her will or let her die of starvation – was recently considered by an English court.

The term force-feeding has a lot of baggage, especially in England, where hunger-striking suffragettes were force-fed (in a brutal and punitive manner, according to contemporary accounts) as were, more recently, imprisoned IRA hunger strikers.

Voluntarily starving to death has links with the rational suicide debate, and attracts largely disapproving attention from ethical, legal and religious sources. The court was between a rock and a hard place indeed.

The case

In brief, the facts of the recent case are:

“E” is a 32-year-old woman who has refused food to a point where she is clearly dying. Indeed, she has been admitted to a community hospital as a palliative patient.

E has indicated, in writing and repeatedly, that she does not want to be kept alive by attempts to feed her, or to be resuscitated in the event of cardiac arrest.

Her parents had reluctantly accepted this, given that E had suffered from anorexia nervosa for decades, and the prognosis for recovery was grim.

The local authority wanted to know if E should be protected from this fate, and took the matter to court.

E, while described as “intelligent”, “articulate” and even “charming” is deeply troubled, abusing alcohol and opiates, and suffering from a personality disorder.

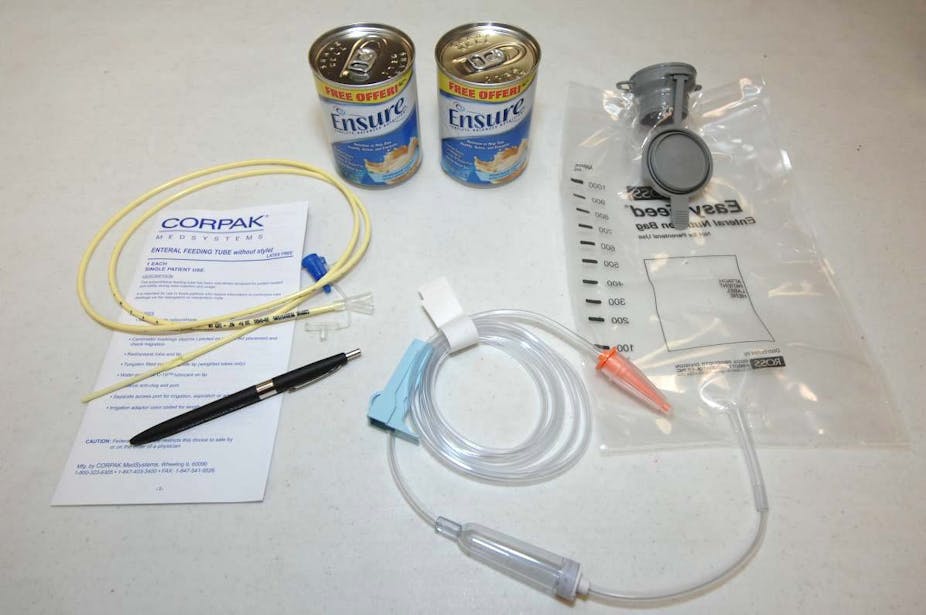

The judge ruled that E should be restrained, physically or chemically, for a year and force-fed, recognizing that it would cost over half a million dollars to achieve this – and that it was likely that she would not change her view.

He declared that all E’s stated wishes, despite their consistency over time, were not valid as she lacked the capacity to make decisions about her care and lifestyle. The main cause of this lack of capacity was her weight loss and low BMI – based on the idea that a BMI of 17 is needed to ensure that E has an adequately functioning brain. E’s BMI is currently around 11.

Autonomy, capacity and volition

Decision-making capacity is the cornerstone of autonomy – all accounts of autonomy from JS Mill onwards acknowledge this. The bigger the decision (that is, the graver its consequences), the more capacity is required. Mill famously offered no suggestions as to what capacity is, or how to test it, so this task has fallen to others, and many have taken on the challenge.

Put most simply, capacity requires the ability to value and the ability to act. By “act” we would normally mean to communicate a choice. “To value” is more complex: it is a composite of understanding, appreciating, reasoning and having a set of values and goals as a reference point.

In Australia, these goals and values can be irrational – it’s not necessary for others to be able to agree with, or even understand these values for the person to be considered competent (to possess adequate decision-making capacity).

In this case, the judge didn’t explicitly state which of the elements of capacity E lacks, and has lacked for some years. She can communicate, and her intelligence is favourably commented on – E having been for several years a medical student. Her written and verbal comments make it clear that she can appreciate her situation, and is aware of the consequences of her actions.

The failure must then lie in her reasoning, influenced by the detrimental cerebral effects of severe malnutrition and the widely-held view that sufferers from anorexia have a distorted body image that renders them incapable of a reasoned approach to their own care.

The bigger dilemma

The problem is this: what if E is subjected to the course of treatment mandated by the court (however impractical that seems), regains weight to the target BMI of 17, writes the same advance directive and stops eating again? Do we wait for her BMI to fall below 11, then pronounce her incompetent and start again?

Would it not be better to acknowledge that the real problem here is E’s values – she values not eating above all else, including her own life. This is a value system that most of us find not only baffling but also deeply hurtful and offensive.

To wish to die of starvation in a society of plenty is uncanny, unsettling and scary. E may well have the capacity to decide, as many experts testified, but the court found her decision unacceptable. While this is a parentalistic attitude that most clinicians would find abhorrent, there’s a long-standing jurisdiction (parens patriae) that allows courts in England and Australia to make such a judgement.

Unsurprisingly, the judgement has proved deeply divisive. I personally find it worrying for this reason: what is to stop courts from using their jurisdiction to curtail our freedom to make bad decisions? Our dignity as humans resides in our ability to make our own decisions – good or bad.