What does a thriving natural world look like? Chances are, your mental image is a lot emptier than your parents’ and grandparents’. This is due to an often-overlooked phenomenon called “shifting baseline syndrome”, which makes conserving nature even harder than it already is.

Fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly noticed in the 1990s that his fellow researchers tended to compare current fish stocks to a baseline set at the beginning of their own careers.

As each generation of researchers was replaced by the next, the point of comparison got smaller as the fish stocks shrank in size and number. Over time, we underestimate the true extent of long-term decline in nature, because we start from a baseline that’s already degraded.

Pauly coined the phrase “shifting baseline syndrome” to describe this phenomenon. But it isn’t just scientists who are affected; it can also apply to our own lives. Rather than just reminiscing about the landscapes you saw when you were a child, have you ever wondered what they would have looked like when your grandparents, or great-grandparents walked through them?

What animals and plants would have been there? How many would there have been and how often would they have strayed into your ancestors’ view? It’s a thought that challenges us to reset our baseline expectations of what our environment looked like, and indeed, could look like again.

The extinction of experience

Around the world, our unreliable memories and our failure to talk about the natural world between generations means there is an extinction of historical knowledge and experience. This allows important trends in nature to go unnoticed. With each new generation, the current and more degraded state of nature is established as the new “normal”.

That being said, shifting baseline syndrome can be difficult to prove. For example, research suggests that populations of moorland mountain hare in the eastern Scottish Highlands are just 1% of their density in the 1950s. The Scottish Game Keepers Association sees it differently, however. It reports that Scottish hares remain among the most abundant in Europe and that the number culled has been stable since 1954, suggesting the population is relatively unchanged. What’s behind this discrepancy?

It’s difficult to be sure – long-term ecological data is hard to come by and what is available is difficult to analyse. But could it be an example of shifting baseline syndrome? Could younger generations of game keepers be working harder to find and cull the same numbers of hares as their predecessors, masking an overall decline in hare numbers year on year?

The change between a few generations can be stark, but arguably this is only the tip of the iceberg. What would our landscapes have looked like to the first humans that colonised them?

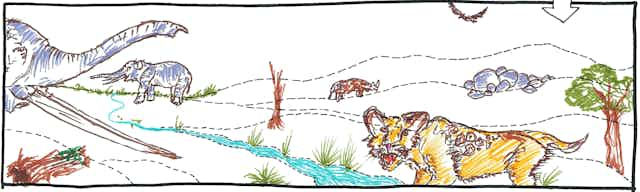

While we can’t ask those early pioneers, research into prehistoric ecosystems paints a pretty dramatic picture. The last time the climate was similar to today was in the last interglacial, between 130,000 and 110,000 years ago. Humans (Homo sapiens) had yet to arrive in Britain.

Hippos swam in the Thames, while the riverbanks hosted straight-tusked elephants, lions and other giants. All over the world, large communities of megafauna – rivalling or exceeding those in Africa’s Savannah today – were the norm until humans arrived.

Resetting our ecological baselines

As part of a project working with young people, our team of scientists from Sussex University, the Sussex Wildlife Trust, and others collaborated with local artist Daniel Locke to create a graphic short story of Britain’s natural and human history, which aims to combat shifting baseline syndrome.

Each illustration represents a landscape from different periods of Earth’s past. It’s easy to see that living in each period would give a very different sense of what kind of animals and scenery you would consider to be “natural”.

People between the ages of ten and 25 years old were then invited to share their views on what they like and don’t like about their landscapes today, and then drew visions of the natural world they would like to see in the future.

What they expressed was a desire to see ecosystems with not just more of the wildlife that’s currently there, but the return of species which have disappeared. There was also an undercurrent of sadness about litter and the present absence of wildlife, and hopes for more sustainable lifestyles in the future.

The visions created were wonderfully diverse, although with some common themes. These included wild and natural areas, sustainable production and humans coexisting peacefully with wildlife. Occasionally, dinosaurs and unicorns turned up in these visions of the future, highlighting free imaginations and perhaps the influence of TV and social media on people’s baseline.

Rewilding our imaginations

Can these wilder visions become a reality? Rewilding has been described as the optimistic conservation agenda. It seeks not only to halt nature’s decline, but ultimately to reverse it by restoring functioning ecosystems. It focuses attention on ecological processes by, for example, returning missing species that play essential roles in delivering them.

In Britain, the beaver is the prime example. This industrious ecosystem engineer can remodel whole river catchments, restore wetlands, reduce flooding downstream and create the conditions which many other species need to thrive.

But one of our best-loved naturalists is unconvinced. Sir David Attenborough has cautioned against reintroducing lost species such as the beaver, emphasising a need to focus on helping the species we have left.

We don’t believe reintroducing lost species to be a distraction from nature’s crisis. We think it has the potential to be a proactive step towards creating more self-sustaining ecosystems. Accepting shifting baseline syndrome would mean progressive damage to the natural world, even with our best efforts.

The greatest value in rewilding is perhaps therefore in the mind. By broadening our imagination and what we can expect from the environment, we can raise our ambitions for the natural world we leave to future generations.