Today marks the 50th anniversary of Australian forces arriving in Vietnam – the beginning of a war that had a huge impact on social and political life here in Australia and abroad. The Conversation will be looking at the war’s legacy throughout a number of articles over the next week.

Today, visitors to Vietnam can still visit the war that ended nearly 40 years ago; the Cu Chi tunnels where the Viet Cong famously lived beneath the occupying forces are now a popular attraction on the edges of the sprawling and rapidly growing former Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City.

The absorption of this site within the rapidly growing economy of the former capital of South Vietnam is a powerful symbol of how the past has been almost seamlessly absorbed into the fabric of modern Vietnam.

The starting point in coming to understand contemporary Vietnam is that the “American War”, as it is known locally, has faded in the country’s collective consciousness.

Those over 65 years with clear memories of the conflict are less than 6 percent of the population. With no one to remember the war the country has moved on, living now in a new economic and geo-political reality.

Recovery through economy

Although the ending of the American War in 1975 brought years of great economic hardship, due to failures of the communist economic model, excessive militarisation and an economic embargo imposed by the US, the economy has been rapidly transformed since Doi Moi (economic renovation). This started in 1986 and was followed by the normalisation of relations with the United States in 1995.

The process of economic integration, usually described as creating a socialist market economy, led to Vietnam joining ASEAN in 1995 and accession to the World Trade Organisation in 2007.

In this time, there has been a remarkable economic transition highlighted by Vietnam moving from being a net importer of rice to the second largest exporter in the world after Thailand. Petroleum, coffee and textiles are now the largest exports.

There has also been huge economic expansion and growth of key cities, but the transformation is uneven, with rural poverty widespread and the economic miracle still very vulnerable due to its dependence on cheap labour. As with many developing countries, the focus of government policy is on advanced manufacturing but this transition is still uncertain.

Fading memories

With a population of more than 90 million in 2011 and a median age of 27.8 years, most people have limited knowledge or understanding of the war or its impacts. As is often the case, the survivors of human tragedies are reluctant to revisit the past, and school curricula in Vietnam give only passing attention to the American War.

Consequently, most Vietnamese appear to know little of the war or its consequences, and its mention evokes little reaction.

For the present generation the United States is a cultural icon. Media images of beautiful people enjoying a wealthy life style are everywhere, and the advertising industry is well developed, particularly in the major cities of Vietnam.

That the American War has had such a limited impact on the popular psyche is not entirely surprising. More deeply etched are nearly 1,000 years of Chinese rule and, to a lesser extent, almost 100 years of French occupation.

Its northern neighbour with a population 16 times larger than Vietnam remains a menacing economic and political force; two examples underline this point. First, in 1979 China briefly invaded northern Vietnam in retaliation for its successful invasion of Cambodia and defeat of the pro-China Khmer Rouge government.

Second, recently tensions in the region have escalated as China enforces its dubious territorial claims over the South China Sea (East Sea). And yet for all this, despite these tensions, the government accepts China as a major investor and trading partner.

Growth in the combined value of imports and exports has been spectacular, rising from $US3 million in 2000 to $US17.8 billion in 2008. In other words fear and suspicion of the expansionist ambitions coexist with a necessary economic and political relationship.

The war’s impacts

While the war is not part of the popular consciousness, the consequences are ubiquitous. Wartime deployment of the chemical defoliant Agent Orange (containing the carcinogen dioxin) has rendered vast tracts of land useless and there is a high incidence of death and deformities resulting from contact with dioxin residues.

While the US does not officially acknowledge the effects of Agent Orange, it is assisting with remediation; for example, there are currently major projects to remove contaminated soil from around from US airbases like Da Nang where inadvertent dumping occurred.

Similarly, unexploded munitions have rendered up to 20 per cent of the country uninhabitable; they also impose a lethal legacy, with an estimated 42,000 killed and 62,000 injured since 1975. Equally notable is the relatively neutral reporting of these issues in the state controlled media, suggesting great sensitivity to its ally, the United States.

This is not surprising in view of the increasingly close economic and military ties between the two countries.

Powerful testimony to this shift is a series of events beginning with the 2010 Vietnamese government announcement that Cam Ranh Bay, the best deepwater port in South East Asia, would be opened to foreign naval vessels for docking and repairs. Subsequently US naval vessels have routinely visited the port.

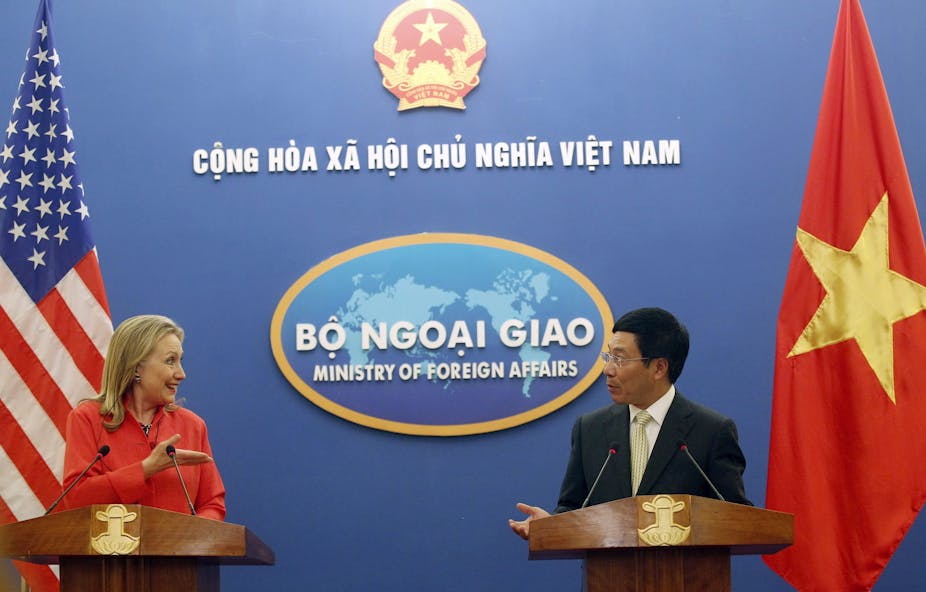

In June 2012, the US Secretary of Defence, Leon Panetta, visited Hanoi to help Vietnam deal with “critical maritime issues”, which is widely interpreted as code for containing China.

Contradictions and consequences

While memories of the American War may have been lost, the human and environmental consequences are, and will continue to be, enduring.

But Vietnam must play the game of international trade and relations – close ties with the US are both a geo-political necessity and a major source of economic advancement. Ironically, as is the case with its neighbour China, this successful relationship is a challenge to the moral foundations of the socialist state and to its past.

See Part 2 of the series about Australia’s involvement in Vietnam here:

Vietnam and Iraq: lessons to be learned about mental health and war