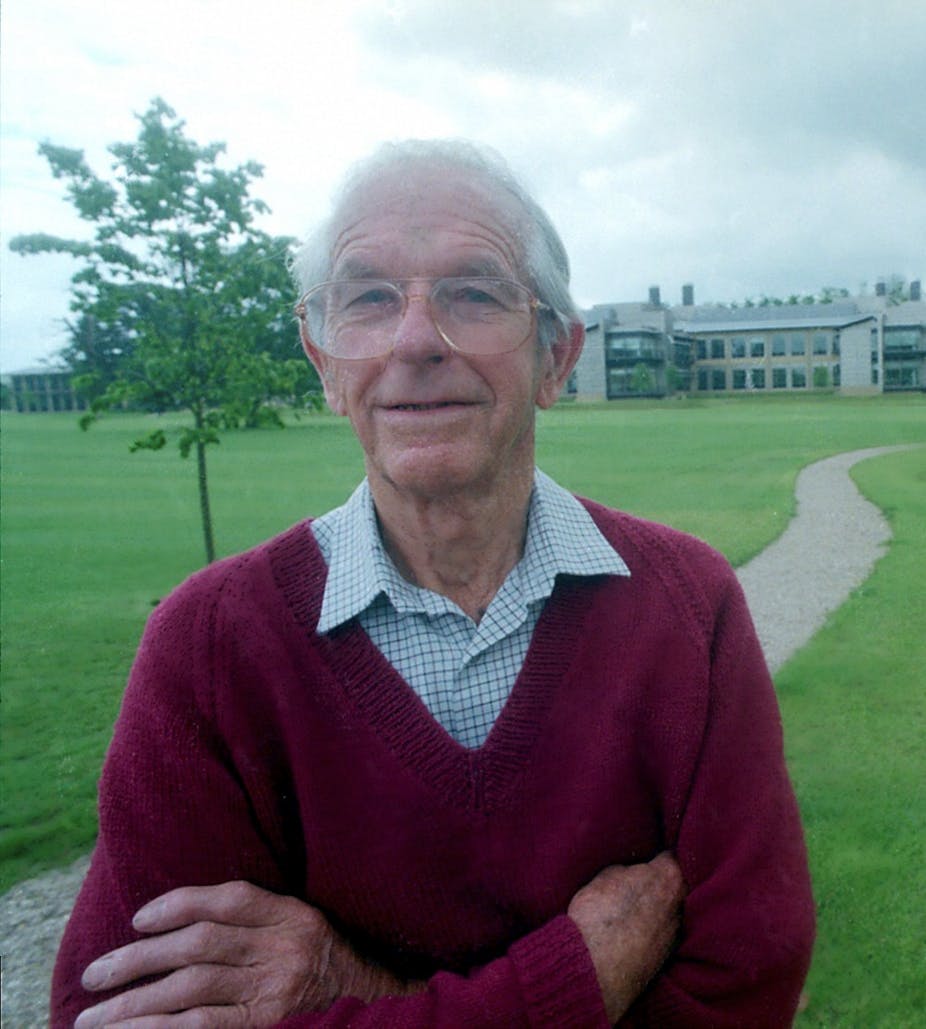

This week Fred Sanger died at the age of 95. His name is probably unfamiliar to most, but he is considered one of the greatest chemists of our age. He is the only person to have won two Nobel prizes for chemistry (only three others have won two Nobel prizes – Marie Curie, Linus Pauling and John Bardeen).

Sanger’s lack of fame is in no small part due to his humble nature and modesty. His sole autobiographical article, written five years after his retirement, starts with the self-deprecating comment: “I was not academically brilliant”. But there is no false modesty here, the article makes no mention of the numerous prizes and honours bestowed on him. These included a knighthood which he turned down, not for any moral objection to the honours system, but because he did not like the idea of being addressed as “Sir”.

Sanger spent his career studying the three fundamental polymers of life – proteins, RNA and DNA. Each of these chemicals play critical roles in biology and each of them are made from long sequences of building blocks. It had long been known that DNA and RNA were made up of strings of just four bases, while proteins are more complicated, consisting of strings of 20 building blocks called amino acids. However, just knowing this is like understanding that sentences are made of letters but having no idea what order the letters come in. Sanger strove to decipher the order of DNA and RNA’s bases and protein’s amino acids.

Other great (and many familiar) names such as Francis Crick, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin and Max Perutz worked on the 3D structures of these molecules. But Sanger’s work was more fundamental and arguably more useful – he laid the bedrock on which some of the greatest achievements of 21st century science such as the Human Genome Project and all that has followed were built.

Sanger started his research career in 1943 on proteins. His Quaker upbringing led him to be a conscientious objector, so he was excused from fighting in World War II. He chose to work on insulin, partly because of its medical importance, but also for the practical reason that he could buy it at the local drugstore. It took him 12 years of work in a laboratory to come up with a solution. This dogged persistence and daily lab work characterised his scientific career:

Of the three main activities involved in scientific research, thinking, talking and doing, I much prefer the last and am probably best at it. I am all right at the thinking, but not much good at the talking.

After this success Sanger entered a period that he described as “lean years with no major success”. He had some sage advice on how to deal with these periods that affect many careers, not just scientific ones:

I think these periods occur in most people’s research careers and can be depressing and sometimes lead to disillusion. I have found the best antidote is to keep looking ahead. When an experiment is a complete failure it is best not to spend too much time worrying about it but rather get on with planning and becoming involved in the next one. This is always exciting and you soon forget your troubles

This quote speaks volumes about his values as during this “lean” and “depressing” period Sanger was awarded, for his work on insulin, one of his Nobel Prizes.

This period came to end when Sanger began work on sequencing RNA and DNA. In 1971, state-of-the-art science had managed to determine the sequence of a stretch of DNA just 12 bases long (not much use considering the human genome consists of 3 billion bases). By 1978 Sanger had extended the record to 5,386 bases and then to 48,502 bases by 1982. These advances demonstrated that it was now possible to sequence vast stretches of DNA. It was for this work that he was awarded his second Nobel Prize, in 1988. But, probably of more value to Sanger was the knowledge that the DNA sequencing he developed made the global Human Genome project (instigated in 1990 and involving thousands of scientists) possible.

As far as Sanger was concerned, his DNA sequencing method was the climax of his career – and so at the age of 65, at the top of his game, he retired and gave up research. Retiring at 65 may not seem odd, but its is rare for a top scientist where a lifetime spent single-mindedly pursuing knowledge is a hard thing to give up.

Sanger was different. He felt the need for a lifestyle change and heeded the call of his rose bushes. He also wanted to make space for younger scientists, many of whom, through his nurturing, went on to win their own Nobel Prizes. So for the next 30 years he focused on his gardens in Cambridge, never once revelling in the glory that was so rightfully his.