For more than 25 years, New Zealanders have consistently rated freshwater health as one of their leading environmental concerns. But the issue is strikingly absent from the 2023 election campaign.

Debate of the controversial new water reform law – which places the management of drinking water, wastewater and stormwater with ten publicly owned entities instead of local councils – has been noticeably muted.

Similarly, discussions of the 2020 Essential Freshwater package, which was the government’s response to New Zealanders listing freshwater as the second most important policy issue in 2017, are nowhere to be seen.

Part of the reason could be that the regulatory approach of the Essential Freshwater package has met resistance from farmers and landowners who feel growing pressure from compounding environmental regulations.

Given this, the continued absence of environmental markets for addressing scarcity and improving freshwater quality in New Zealand streams and rivers is a marked policy omission.

Elsewhere in the world, water trading can help improve efficiency and drive water conservation. Trading helps to shift water from low-value to high-value uses or from areas with relative abundance to places of relative scarcity.

Motivated by what we observe in New Zealand and internationally, our new research offers an innovative, alternative approach for managing freshwater in small catchments.

Freshwater and property rights

Freshwater is allocated on a “first come, first served” basis in New Zealand. Since 1991, consents or permits have been granted to water users by local authorities under the Resource Management Act (RMA), usually for periods of up to 30 years.

Although these consents act as de-facto property rights to water, they are not defined as such under the RMA. This makes water “rights” open to interpretation when challenged under law.

Consent holders are also unable to easily trade and exchange their rights. This means water is not necessarily used in the most efficient or effective way. This potentially exacerbates issues of over-allocation and declining water quality.

Part of the ambiguity around water rights is driven by unresolved questions about proprietary rights and Māori interests in water that have arisen because of inconsistent translations of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. These complexities make the establishment of property rights to freshwater complicated, with run-on effects for the types of policy tools that can be adopted.

Formal water markets, like those in Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin, require property rights to be well defined, defended and divestible. They also have several institutional preconditions, such as low transaction costs and a large number of active traders. These make them appear poorly suited for many small New Zealand catchments.

However, our research suggests that designing water markets as “clubs” could circumvent some of the institutional challenges of implementing formal trading regimes in small New Zealand catchments.

Water clubs: a new model for small catchments

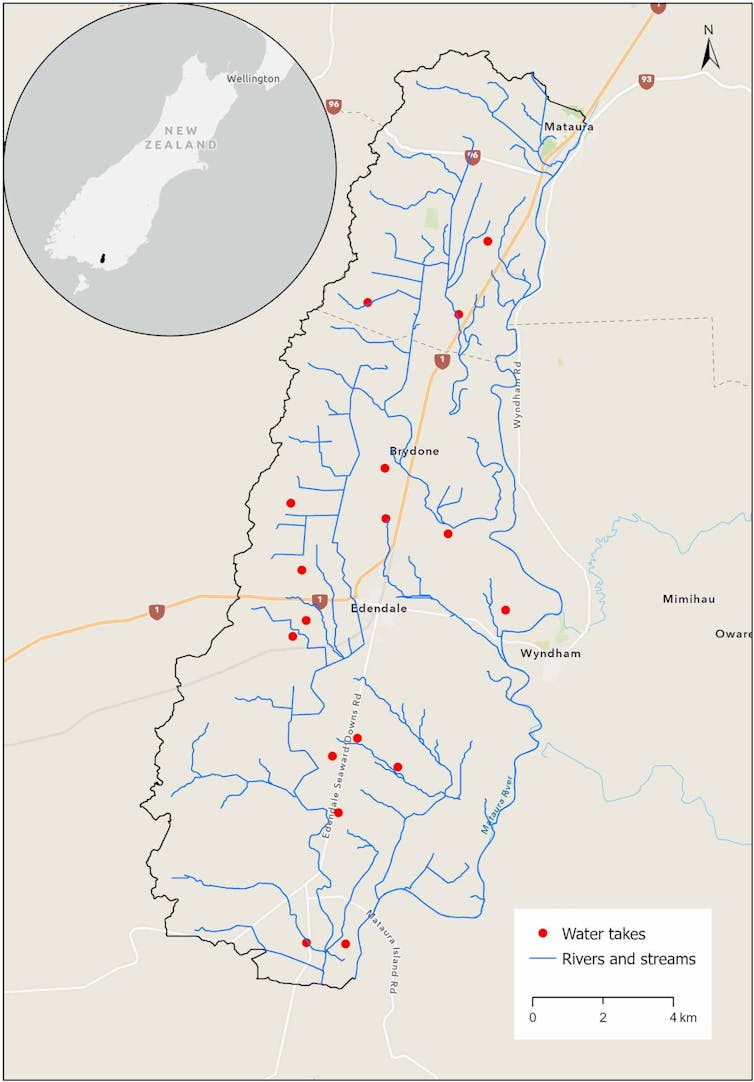

Unlike other countries characterised by large river basins and many active water users, many parts of New Zealand have small catchments with few active users.

Economic theory argues these contexts are unsuitable for formal trading arrangements because the transaction costs associated with establishing an active water market are likely to outweigh any potential efficiency gains from trade.

Designing (or redesigning) water markets as clubs could get around some of the political and economic complexities of New Zealand’s freshwater policy landscape by permitting small groups of users with shared interests to voluntarily trade their water endowment under certain conditions.

In small catchments, the introduction of trading at the group level has the potential to increase the public-good aspects of water such as water quality. It could also improve community wellbeing and encourage people to internalise the costs they may be imposing on other group members.

Read more: Murray River water sales: better for farmers and the environment

We also find the club model performs best when the number of active traders is low. This challenges the common assumptions regarding group size and effective market performance.

These results suggest that if water users, such as a group of like-minded farmers involved in a catchment group, were given permission to trade their water consent with other members of their group, they could improve the health of the environment.

They could also enhance the net benefits of their own private agricultural production, compared with the current regulatory status quo.

Although this new “club model” does not comprehensively address the outstanding issues of Māori rights and interests in freshwater, it provides an innovative way to adapt a trading regime to suit New Zealand’s political and geographical context.

Surely innovation is something political leaders would want to discuss on the campaign trail.