Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names of deceased people.

In the quiet of the State Records Office, I have spent many hours searching for knowledge about my family.

In Australia’s archives, we can find letters written by Aboriginal people to the government. We hear echoes of their voices in their words on the page.

Some of these letters express grief, anger and frustration. Some protest the injustice of oppressive legislation.

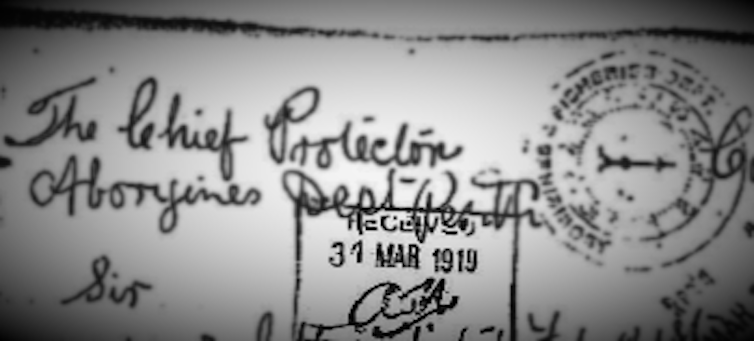

Archives in the State Records Office of Western Australia hold hundreds of letters written by Noongar people to the Chief Protector of Aborigines and other government officials from the turn of the 20th century. The letters were captured within manic record-keeping systems used to surveil and control Aboriginal people.

These letters are an historical record of the agency of Noongar people to reckon with systematic human rights violations under the 1905 Aborigines Act and in particular the cruel administration of Chief Protector A.O. Neville from 1915 to 1940.

Aboriginal people are working to reclaim knowledge about our families in archives. The recovery of these letters has become a catalyst for storytelling, as we piece together archival fragments and living knowledge.

My searching has recovered many letters written by my family. It has recovered stories that had been lost for generations.

Heartbreaking pain

Within personal files and those relating to institutions for Aboriginal children is a collection of precious letters written by Noongar mothers and fathers to Neville pleading for children who had been forcibly removed as part of the Stolen Generations.

These letters are handwritten, often in faded pencil on yellowing paper with worn edges.

Emotions linger in words, in the handwriting itself, or in other marks on the page. A small indent is imagined to be the resting of the pencil on the page as the letter writer collected their thoughts.

Under the 1905 Act, Aboriginal parents were not the legal guardians of their own children. Neville unjustly became the guardian of every Aboriginal child in Western Australia under the age of 16.

Read more: Friday essay: reflections on the idea of a common humanity

Decades of pleading for children unfold within these letters, revealing deep Noongar truths about unending love and care for children. They are love letters written by mothers and fathers, and sometimes by children themselves.

Reading these letters, we come to feel – rather than know – the heart-breaking pain of having a child taken from you.

The words on the pages of these letters sound with a spirit of tenacity to restore broken connections within families.

A personal record of love

One of these many histories belongs to my grandmother’s grandfather, Noongar man Edward Harris. He campaigned for more than a decade between 1915 and 1926 for the return of his four children: Lyndon, Grace, Connie and my great-grandmother Olive.

He wrote these letters from the heart, a place where he held his children close to him. His letters, captured within archives, have become a treasured historical record of his love for his children.

I never expected to find him in archives and to listen to his voice in his words on the page.

Edward’s letters are assertions of humanity and human rights. Assertions of rights as a father.

In a letter to Neville dated February 1 1918, he writes:

And now before bringing this letter to a close I again appeal to you to have my children placed in my care, and to remind you that I am their father, and if you cannot do that, I’ll have to try some other means to have my children restored to me, either through the press or else a court of justice.

Edward met all the demands Neville placed on him in their correspondence for the return of his children: he could provide good character references; he had a stable job as a farm manager; he had a good home there; he had a wife to take care of the children; he had money to send them to school.

In a letter dated December 31 1918, he writes:

I am anxious to have my children home with me […] In order to have them with me, I have done what you thought was necessary.

On March 29 1919, he writes:

I can never convince myself that you are anxious for me to have my children back. I have told you before that you are hostile and biased, I still believe you are the same […]

[I]n all my dealings with you re the children you have raised too many obstacles and created too many difficulties, the result to me has always been disappointment. I have carried out all the conditions you have imposed on me, and I expect you to fulfil your promises re the children.

Neville refused to return Edward’s children from Carrolup Native Settlement near Katanning, and later Moore River Native Settlement.

This refusal had everything to do with oppression, and nothing to do with Edward’s ability to love and care for his children.

Reading these letters, from many parents, proves time and time again the structural nature of child removal.

Edward was a family man whose advocacy was motivated by his love and care for his children. He demanded the repeal of the 1905 Act. He held Neville to account for his abuse of power.

On August 21 1920, he writes:

[…] it would be a hard matter for you or anyone else to convince me that it is in the interests of the children that you are keeping them shut up at Carrolup. Your past actions show that you are malicious, you have never missed an opp[o]rtunity of hurting me. Not once. Also you have used your position as Protector and the Aboriginal Act to gratify your malice.

You speak of doing the best in the interests of my children. I cannot see it […]

Edward’s advocacy continued as he wrote letters, requesting a departmental inquiry into Neville’s refusal to return his children, and attempting to take his case to court.

In a letter to the Deputy Chief Protector of Aborigines, in March 1920, he writes:

Several times I have asked him [Neville] on what grounds does he refuse to restore me my children, and so far I am still in the dark as to his reasons for holding my children. Of course I will apply again for my children and also ask for an inquiry as I consider that I have been victimised by Mr Neville.

The way I have been treated by that gentleman is an outrage to one’s feelings and affections.

It is an outrage to anyone’s feelings and affections.

Edward, with his brother William Harris and many other Noongar families, went on to establish the first Aboriginal political organisation in Western Australia, the Native Union, in 1926.

William Harris described the organisation as a “protective union” for all Aboriginal people.

The Native Union demanded the repeal of the Aborigines Act 1905, in particular the power of the government to forcibly remove Aboriginal children from their families. It also held Neville’s administration to account for its systematic violation of Indigenous rights.

The Western Mail reported that during a meeting with Western Australian premier Philip Collier in 1928 William Harris said:

The department established to protect us, is cleaning us up […] Under the present Act, Mr Neville owns us body and soul […]

Taking up pen and paper, Edward Harris and many other Indigenous activists of his generation were involved in fundamental work to advocate for transformative discourses of humanity and human rights.

For our generation, their letters humanise histories of colonisation and intergenerational trauma.

Recovery and revitalisation

The recovery of this collection of letters is a practice of truth-telling about Stolen Generations. These letters reveal Aboriginal truths about unending love and care for children. They reveal truths about our collective humanity. These letters restore some humanity to the inhumanity of the Stolen Generations.

Recovering Aboriginal cultural heritage in archives contributes to the revitalisation of our storytelling as branches of knowledge about who we are and where we come from.

This is the legacy of these letters for the next generations.

These letters, some written more than a century ago, echo our current demands. Aboriginal people continue to contend with contemporary practices of child removal.

As the Uluru Statement reflects: “This cannot be because we have no love for them.”

It is an honour to recover these letters, to shine some light on the long history of this love and the love in my own family story, too.

All excerpts of Edward Harris’s letters have been reproduced with permission. These excerpts may not be reproduced outside of the context of this article without the author’s permission.