For many of us back in 1991, it felt as if the planet tilted slightly further on its axis when Smells Like Teen Spirit — the lead single from Nirvana’s Nevermind album — began to dominate the airwaves. The song’s compelling fusion of blast furnace punk, whimsical melody and inscrutable lyrics was unlike anything else commercial radio had embraced up to that point.

Friday September 24 marks the 30th anniversary of the release of Nevermind. Materialising apparently out of nowhere, within four months the album had shoved its way to the top of the US charts, dislodging Michael Jackson’s Dangerous in January of 1992. It did almost as well in Australia, reaching number two.

Nevermind has gone on to become a recording phenomenon, with over 30 million copies sold. Nobody saw this coming, not least the band’s record company. John Rosenfeld, who worked for Nirvana’s label, Geffen, at the time of its release has said they originally projected sales of 50,000.

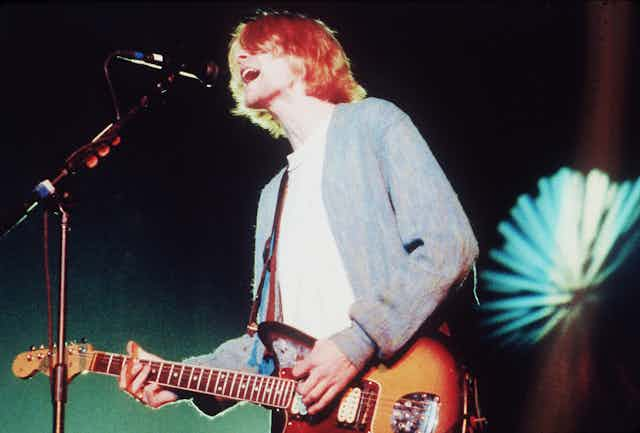

Nirvana formed in 1987 in the logging and fishing town of Aberdeen, Washington. Featuring guitarist, vocalist and principal songwriter Kurt Cobain, bass player Krist Novoselic, and new drummer Dave Grohl, Nevermind was Nirvana’s second album — the first for a major label.

Instantly identifiable by its cover image of an infant swimming toward a fish hook baited with a dollar note, it included three more frenetic-cum-fragile singles — Come As You Are, Lithium and In Bloom — as well as two haunted acoustic tracks — Polly, a repudiation of sexual violence, and the cello-bathed Something in the Way, which alluded to homelessness.

A range of factors converged to draft Nirvana into the mainstream with Nevermind. Certainly, the quality of the songs helped.

So did Teen Spirit’s incendiary video, which conveyed generational antipathy through robotic cheerleaders, a swarm of convulsive teens and a wizened school janitor (Cobain having held down just such a job for a short time). Producer Butch Vig and mixer Andy Wallace were also vital, applying precisely the right amount of gleam to the band’s coarse-grained, jet engine roar.

Significant, too, were the many post-punk musicians who in the 1980s shaped what Nirvana biographer Michael Azerrad subsequently termed a “shadow music industry”. This underground faction of American bands — Minutemen, Hüsker Dü, Dinosaur Jr, Mudhoney, Sonic Youth and others — forged a crucial alternative, do-it-yourself aesthetic pathway through the ultra-conservative Reagan-Bush era.

Sometimes important art takes time to inject itself into the bloodstream of the culture. While the Velvet Underground are now acknowledged as a pivotal force in early rock music, at the time their records had limited critical cache and sold poorly. With Nevermind, however, audiences caught on quickly, leaving cultural commentators scrabbling to hook on to a hurtling zeitgeist.

Three stars from Rolling Stone

Bass guitarist Novoselic has since spoken derisively of the many journalists who initially mocked Nevermind before later claiming “they loved it from the start”.

In hindsight, this seems slightly exaggerated. Some publications did completely overlook the record at first. A few came in with fists flailing: the Boston Globe referred to it as “moronic ramblings”.

Others, though, were prescient in their praise. Melody Maker’s Everett True prophesied Nevermind would “blow every other contender away”.

Renowned author Greil Marcus expressed a surprising preference for Nirvana’s murky debut album Bleach, while Chad Channing, the drummer replaced by Grohl to make Nevermind, complained the record’s major label sheen wasn’t true “grunge”.

But the most revealing response came from Rolling Stone magazine, whose initial reviewer Ira Robbins was one of the smarter music writers of the time. He concluded that Nevermind found Nirvana “at the crossroads — scrappy garageland warriors setting their sights on a land of giants”. The magazine’s editors hedged even more bets by adding a three-star rating, the rock press equivalent of consigning a record to eternal mediocrity.

Rolling Stone eventually yielded to popular sentiment. In 1992 there was a revised four-star review. Then, in 2004, Nevermind’s standing was upgraded even further: a five-star ranking in that year’s Rolling Stone Album Guide. This followed on from 17th place in the magazine’s 2003 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list, putting it up there with Highway 61 Revisited, Are You Experienced? and Marquee Moon.

Robbins, too, seemed determined to set the record straight as soon as the opportunity arose. For the 1996 edition of his Trouser Press Guide, the review of Nevermind — one of the longest in the entire volume — deemed it “the Rosetta Stone of 90s punk-rock”.

Read more: Kurt Cobain and the search for a sincere rock star

By the 1990s, music criticism was changing. A glut of available recordings — nowadays an overwhelming deluge — coincided with further fragmentation of the rock genre both in style and format. At the same time, publications like Rolling Stone were increasingly seen as tied up with traditionalist, patriarchal notions of popular music history.

Kurt Cobain voiced the alienation of a marginalised youth who couldn’t care less about the old rules. His group’s music was nowhere near as unorthodox as, say, that of close friend Dylan Carlson’s influential drone-metal project Earth. But Nevermind was a subversive assault upon the rock elite from within: a big guitar sound without the big-dick attitude.

Into the stratosphere

We’ll never know exactly what sent Nirvana into the stratosphere while artists of comparable brilliance didn’t transcend their relatively minor standing. After all, in the 1980s quite a few of us in Australia were convinced each new Go-Betweens record would be the one to spark global domination.

Similar could have been said for Public Enemy circa 1991, or for Sleater-Kinney (like Nirvana, hailing from the Pacific Northwest) a few years after.

No doubt Cobain himself would have conceded being a white, all-male, US-based guitar-bass-drums outfit (albeit one from the seamier side of the tracks) gave them a leg-up on these and many other contenders.

Read more: Redefining the rock god – the new breed of electric guitar heroes

Cobain’s amalgam of influences was expansive, from the Raincoats, Iggy Pop, Ian MacKaye and REM to Samuel Beckett and William S. Burroughs. He wasn’t above raiding the classic rock fortress for ideas, but also excavated deep below in search of subterranean misfits to emulate.

Nonetheless, Boston’s Pixies were the main forebears of Nirvana’s trademark quiet-loud-quiet sound. As it happens, I recall The Happening, an extraordinary Pixies song from 1990, giving me the same kind of this-could-be-the-one jolt that Teen Spirit did a year later. Yet one is regarded as a historical turning point, the other an obscurity.

Wherever the alternative banquet began, big business and media were always going to be quick to gatecrash. As Nevermind broke, the corporate vultures weren’t just circling: they’d already flown in to commence tearing the last morsels from the skeleton of post-Reagan America.

As journalist and political analyst Thomas Frank noted in his important 1995 essay Alternative to What?, by the time of Cobain’s 1994 death by suicide, the commodification of rebellion was complete. For the ultimate proof, Frank pointed to a cynical MTV advertisement found in the business sections of certain newspapers and magazines. It featured an image of a grunge-styled youth along with the caption: “Buy this 24-year-old and get all his friends absolutely free”.

Corporate scavengers aside, Nevermind continues to stir fans and critics. Its history continues to be told, and many of the sharpest (and best written) recent takes are by Australian writers.

Josh Bergamin’s recent note-perfect analysis sets Nevermind’s success within contrasting milieus of generational disillusionment and executive greed, arguing Cobain and many of his fans engaged in radical acts of political resistance.

Cristian Strömblad uses the context of growing up in suburban Brisbane to tell of how Nirvana helped open up new aesthetic worlds.

Tiarney Miekus explores perennial death-of-rock narratives in light of “the big dumb accident” that was Nevermind.

Conversely, wardens of the conventional rock canon still emerge to disdain the achievements of alt-culture’s “anaemic royalty”. In one resentful, ridiculous critique of the album on the Classic Rock Review website, J.D. Cook concluded Nirvana was “only popular because of Cobain’s suicide”, implausibly overlooking the two-and-a-half years of international acclaim preceding that grim epilogue.

A beginning

To me, Nevermind wasn’t a peak. It was a beginning. Nirvana was a stunning band and Cobain by all accounts a dedicated, intelligent, yet supremely troubled individual whose life always teetered on the chasm’s edge. Until his death partly stalled the show – the imperatives of consumerism ensuring the band’s ghost would continue to post a profit regardless – the music kept getting better.

Cobain’s craft evolved as success lured his social conscience further into the open. This is palpable on the In Utero album (1993), in songs such as Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle and Rape Me (the latter later distorted by those who hid behind a controversial title to evade its prescient, victim’s-eye view of sexual abuse).

Once Nevermind raised Nirvana’s media profile, Cobain continued putting forward positions on different political issues (for instance, after they appeared in drag for the video to In Bloom, he told an interviewer that “at least it brings the whole subject of homosexuality into debate”).

The band’s social justice stance was made abundantly clear in the liner notes for the 1992 compilation Incesticide, which warned sexists, racists and homophobes would not be welcome to sweat in their particular mosh pit. They also contributed a “leftover” of exceptional quality, a song titled Sappy, to the 1993 AIDS fundraiser album No Alternative.

The group even did its best to subvert MTV’s rebellion-into-cash mentality at their November 1993 Unplugged in New York appearance. The show featured gut-wrenching versions of the best tracks from In Utero (Pennyroyal Tea and All Apologies) and a touching three-song gambol with underground mentors Meat Puppets. Topping it off were surely two of the most remarkable cover versions ever performed: David Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World and Lead Belly’s Where Did You Sleep Last Night.

Today, Nirvana’s iconic stature is only confirmed by it being caught up in two of America’s pet modern-day farces: the conspiracy theory (some still claim Cobain’s death was murder) and a multi-million dollar lawsuit (the child depicted on Nevermind’s cover is currently suing the band and others for damages).

As for all that voice-of-a-generation stuff … well, Nirvana’s appeal was hardly universal: they meant something to plenty of people in places like New York and Sydney, probably a lot fewer in Addis Ababa or Tehran.

Nor is the ultimate cultural significance of Nevermind easily pinned down. In that context, it is worth remembering that two other major US events of 1991 — the videotaped beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles and the Luby’s Cafeteria mass shooting in Texas — didn’t exactly portend epochal change in racial equality or gun control.

Nevermind didn’t change the world. But for a while it helped some of us believe the world could change, and that is enough.