In 1967, French theorist Roland Barthes famously declared the metaphorical “death of the author” in his essay of the same name. Barthes rejected the Romantic idea of the author as a unique figure of genius. Still, despite his best efforts, this romantic notion of the heroic, solitary wordsmith lives on today.

In Medieval times, authors were seen as nothing more than craftsmen. But the Romantic poets – Byron, Coleridge, Blake, Shelley – singled out the writer as a figure of “spontaneous creativity”. As academic Clara Tuite has noted,

the Romantic period saw the birth of the literary celebrity, a figure distinguishable from the merely famous author by his or her status as a cultural commodity.

This Romantic writer was seen as either a solitary hero, a tragic artist, a melancholy genius - or all three. In the centuries since, famous authors have been both celebrated and panned, adored and ridiculed.

Since Romantic times, we have often expected writers to be detached from the trappings of celebrity culture, aligning their integrity with an anti-commercial attitude. There is, argues author Joe Moran, a “nostalgia for some kind of transcendent, anti-economic, creative element in a secular, debased, commercialised culture” that we commonly attach to writers. Indeed theorist Lorraine York has asked if we can even use words like “fame” and “celebrity” to describe writers, “those notorious privacy-seeking, solitary scribblers”.

One of the first to question the idea of literary celebrity was the 18th century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who found his own fame something of a burden. More recently, authors such as Jonathan Franzen, David Foster Wallace, and Dave Eggers have struggled with the desire for popularity and credibility. In today’s internet culture, reaction to a famous writer’s actions or utterances is quick and merciless. Next week, a new author will be thrust into the media spotlight, with the announcement of the Booker Prize winner.

Yet interestingly, discussions about the difficulties of being a famous writer rarely include women. The notion of the solitary genius is usually attached to men. A notable exception is the Italian novelist Elena Ferrante – who is famous, ironically, precisely because of her reluctance to engage with literary celebrity. Ferrante writes under a pseudonym, in her words, to “liberate myself from the anxiety of notoriety”.

Ferrante’s recent unmasking by a literary journalist has unleashed a torrent of condemnation.

The extent to which her true identity has been picked over shows how our society craves constant closure, often at the expense of creativity and imagination. As Michel Foucault once noted, literary anonymity is “of interest only as a puzzle to be solved”.

Such is the nature of contemporary celebrity culture that many cannot tolerate the idea of writers who prefer anonymity over fame. So those such as Thomas Pynchon, J.D. Salinger and Ferrante, who have evaded the limelight, have been scrutinised as much for their personal lives as their actual works.

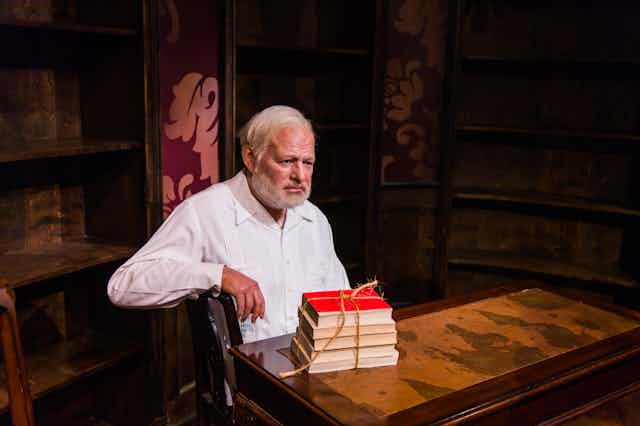

A short history of famous (male) writers

The 19th century writers Charles Dickens (hero of the working class) and Mark Twain (America’s most beloved humourist), were plagued with aspects of their fame. While Dickens was often criticised for appealing to the lower classes, Twain likened celebrities to clowns. Celebrity, he said, “is what a boy or a youth longs for more than for any other thing. He would be a clown in a circus […] he would sell himself to Satan, in order to attract attention and be talked about and envied”.

Yet Dickens and Twain also enjoyed their fame. Dickens was renowned for engaging his audiences at public lectures; Twain also went on speaking tours.

If we fast forward half a century or so, we come to Ernest Hemingway – another author who felt imprisoned by his fame. As theorist Leo Braudy puts it, Hemingway was caught between “his genius and its publicity”. In an undated writing fragment, Hemingway wrote:

We have reached the point where we are ruled by photographers and agents of publishers and writing is no longer of any importance.

He also called fellow writer F. Scott Fitzgerald a “hack” for writing Hollywood screenplays.

Yet Hemingway nevertheless helped promote the “Hemingway myth”, built around ideals of masculinity and genius. He was frequently photographed outdoors, fishing and hunting, or attending bullfights.

Then there was Norman Mailer, the pugnacious, Jewish author of The Naked and the Dead and Advertisements for Myself. In 1960, Mailer stabbed and seriously wounded his then-wife, Adele Morales with a pen-knife at a drunken party. (After pleading guilty to a charge of third-degree assault, he received a suspended sentence.)

Mailer cultivated a public persona that certainly boosted his fame, but did little for his literary reputation. Many critics accused him of wasting his talents by shamelessly promoting himself; he did frequent TV interviews, including a particularly notorious appearance on The Dick Cavett Show, where he and Gore Vidal famously butted heads over Mailer’s public profile and ego.

Indeed, Mailer once called himself

a node in a new electronic landscape of celebrity, personality and status.

Theorist John Cawelti suggests that unlike Hemingway, who lived out to the end an ambiguous conflict between celebrity and art, Mailer “tried to make his public performances themselves into a kind of artistic exploration”. Mailer frequently wrote about himself in the third-person, in an effort to “perform” himself as a character.

Interestingly, at the same time as all this was happening, J.D. Salinger, author of The Catcher in the Rye, famously was living as a recluse.

Franzen and Oprah

In 2001, Oprah Winfrey put Jonathan Franzen’s sprawling family saga The Corrections on her book club list, encouraging her audience to read it. Franzen was invited onto Oprah’s show. He declined, saying he didn’t want his novel placed alongside “schmaltzy, one-dimensional [books]”.

Franzen was widely panned for being a snob. Andre Dubus III, for instance, criticised Franzen’s assumption that “high art is not for the masses, that they won’t understand it and don’t deserve it”.

Media scholar Ian Collinson sees Franzen’s reaction as a symbolic attempt to separate the television celebrity from the novel, an act of “cultural decontamination”. Franzen, he writes, feared his position within the high-art tradition “would be compromised if his novel were subject to such blatant commercialism”.

Yet nine years later, Franzen apologised to Oprah. He was again invited onto her show, this time to promote his 2010 book Freedom. He did not refuse a second time. Ironically, many criticised Franzen for succumbing to the allure of popularity. The old assumptions regarding the incompatibility of literature and celebrity resurfaced, with one critic, Macy Halford, suggesting that “Oprah and Franzen are not terribly compatible personalities”.

This whole saga attests to what Tessa Roynon has called the “damned if you don’t, damned if you do” mentality of literary celebrity. Authors are often seen as having to choose between respectability amongst fewer critics, or widespread popularity at the expense of their reputations. (One article about a speech Franzen gave to students in 2011 was memorably titled, “Touching the hem of Mr Franzen’s garment.”) Like Mailer, Franzen’s career has been marred by the troubled union between mass media presence and desire for literary acceptance.

Celebrity and Sincerity: Wallace and Eggers

One of Franzen’s peers, the late David Foster Wallace, was an author in the Romantic mould; he is associated with the “New Sincerity” literary movement, and his 1996 novel Infinite Jest has been judged by many as a work of genius.

In 2008, Wallace took his own life. Before his death, Wallace was known to have suffered from depression, and he projected an image of the melancholy genius. His opinion of celebrity was less than favourable. His widow Karen Green once noted in an interview that all of the media attention given to Wallace “turns him into a celebrity writer dude, which I think would have made him wince”.

In a 1996 New York Times piece, Wallace claimed that the “hoopla” of celebrity made him want to become a recluse. The cult of celebrity was something he consistently mocked in his work, calling celebrities “symbols of themselves” rather than real people. As with Rousseau and Salinger, the logic went that Wallace “deserved his celebrity”, journalist Megan Garber writes, specifically because he had not sought it.

Dave Eggers is also part of the “New Sincerity” movement. A writer of serious, sentimental fiction, his books include his debut memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, and What is the What?, the fictionalised story of the life of Sudanese refugee Valentino Achak Deng. Eggers also opened the writing centre Valencia 826 in San Francisco, which helps children develop their writing skills (and inspired the Sydney Story Factory and Melbourne’s 100 Story Building.)

Early in his career, Eggers often spoke of wanting to retreat into anonymity. Instead, he seized the reins of literary celebrity. Some then accused him of hypocrisy – in criticising fame while also inviting it. He has also been criticised for “excessive sincerity”, while journalist David Kirkpatrick called Eggers “agonizingly ambivalent”.

Journalist James Sullivan notes that Eggers

treats his celebrity like a gold lamé suit: It’s amusing, absurd and, in his mind, not quite appropriate.

Meanwhile, in her reading of Eggers’ 2003 book You Shall Know Our Velocity, Caroline Hamilton suggests that the central characters “resemble the credibility-obsessed younger Eggers torn between longing for celebrity and legitimacy”.

In a 2000 email interview, Eggers referred to himself as a sellout for having sold many books and appeared in various magazines. As Hamilton writes, the term sellout has less to do with wealth, and more to do with “the popularity that comes with it”. Celebrity, then, remains a problem for those authors wishing to appear genuine and serious.

Where are all the women?

It is striking that female authors are, for the most part, excluded from all these agonised discussions about inner turmoil and perceived loss of prestige. This suggests that women are not often thought of as having substantial reputations in the first place.

Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison, for instance, has frequently appeared on Oprah’s program to discuss her complex, poetically written, novels. In contrast to Franzen, however, Morrison’s credibility was never seen to be compromised in doing so.

Despite the number of talented women writing today for large audiences – Margaret Atwood, Zadie Smith, Joan Didion, and Toni Morrison just to name a few – critics do not often think of female authors as having the kinds of monumental reputations that their male peers possess. The Byronic hero, the Hemingway legend, and the Foster Wallace genius are larger-than-life men.

Women are seldom discussed in such a way – with the possible exception of Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf. Yet this may actually be a blessing for them. Avoiding the expectations that go along with literary celebrity can be an advantage. Female authors may be better able to breach certain boundaries – of genre, style, content – in ways that certain male authors cannot.

Ferrante, for instance, said she explicitly needed anonymity to write honestly. While some may see it as a bizarre sort of compliment to her that she is so intriguing that an Italian journalist spent weeks combing financial and property records to unmask her, she surely deserved the right to her privacy to focus on her own work.

Some of the most interesting genre-defying authors writing today are women such as Morrison, Atwood, and Emily St. John Mandel. Perhaps, then, female authors can more seamlessly defy stringent boundaries that continue to define the literary world when they are not hailed as heroic geniuses.