For centuries, when people thought of witches, they were evil or possessed by evil demons: think of the Salem witch trials or the 16th and 17th-century woodcuts depicting sinister women conjuring demons or flying on broomsticks. These were the sort of women who morphed in fairy tales into the wicked stepmother in Snow White or the evil crone in Hansel and Gretel.

But recent generations of children are more likely to have come across witches as figures of fun: consider Sabrina the Teenage Witch or Hocus Pocus, in which Bette Midler, Sarah Jessica Parker and Kathy Najimy abduct children, resurrect dead lovers and brew potions with comic flair. With the reboot of Hocus Pocus (marking the film’s 25th anniversary) and a new scarier version of Sabrina the Teenage Witch now on the air, the witch as a figure of fun is once again coming to the fore.

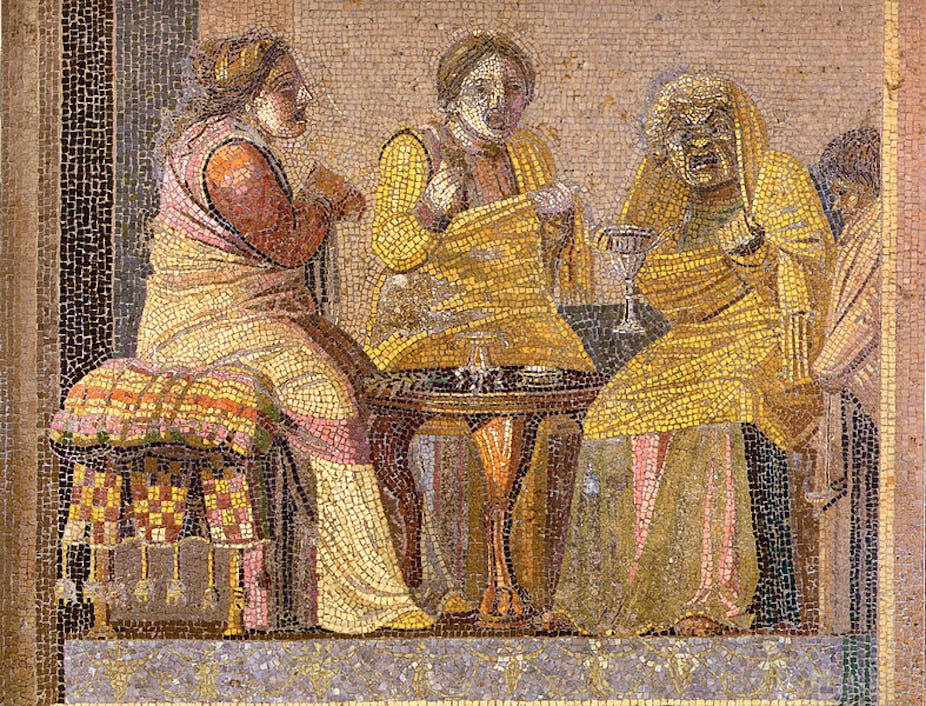

This caricature of the witch predates the sinister medieval version and can be traced all the way back to Roman times. Many of the jokes levelled at witches in popular culture had already been made in Horace’s Satires, published in about 35 BC, and Apuleius’s Metamorphoses from the 2nd century AD.

From temptress to Hag

Horace’s Satires introduces us to Canidia and Sagana as comic hags (strigae) “hideous to behold” – a far cry from the temptress witches of Greek literature such as the bewitchingly beautiful Circe and Calypso. In his eighth satire, Horace assumes the poetic voice of a wooden statue of Priapus, a fertility god (with a huge phallus). Priapus witnesses Canidia and her crony Sagana burning wax images of their enemies in a ritual of sympathetic magic. But their nefarious spells are interrupted when Priapus’s statue farts:

Away they ran into town. Then amid great laughter and mirth you might see Canidia’s teeth and Sagana’s high wig come tumbling down, and from their arms the herbs and enchanted love-knots.

Like the witchy Sanderson sisters in Hocus Pocus who are forced to fly on vacuum cleaners and are baffled by buses, Horace’s hideous witches are at odds with their environment. Fleeing, Horace’s witches leave behind their wigs and teeth and drop their erotic spells – they are generally depicted as laughable characters.

Suspending disbelief

In Metamorphoses – which is the only complete Latin novel to survive – Apuleius gives us the adventures of Lucius, a Greek traveller, who hears other stories from travellers about their encounters with witches before he himself is turned into an ass by the witch Meroe. The novel comically plays on hearsay and scepticism. So when Lucius’s companion Socrates warns him about the dangers of Meroe, he provides a list of impossibilities (known as adynata), claiming that “she can lower the sky and suspend the Earth …”.

This description of impossible happenings is a stock feature of witchcraft in non-comic literature. For example, in Ovid’s own Metamorphoses, the witch Medea claims to draw the moon from the sky and uproot trees when concocting a poison to kill the new wife of her lover Jason. But Lucius, aware of people’s habit of exaggeration when talking of witches, berates his friend:

‘Please,’ I said, ‘do remove the tragic curtain and fold up the stage drapery, and give it to me in ordinary language.’

Boyfriend trouble

The most persistent plot device in both Apuleius and Hocus Pocus is the witch as the woman scorned. Just as Winnie Sanderson kills her unfaithful lover Billy Butcherson in Hocus Pocus, so witches in ancient literature also had to contend with bad boyfriends. In Metamorphoses, Apuleius tells us that the witch Meroe transforms her unfaithful lover:

Because one of her lovers had misbehaved himself with another woman, she changed him with one word into a beaver, because when that animal is afraid of being captured it escapes from its pursuers by cutting off its own genitals, and she wanted the same thing to happen to him since he had intercourse with another woman.

Ever creative, Meroe’s punishment fits the crime and the episode emphasises the sexually predatory presentation of witches throughout the novel. In Apuleius, as in our current popular culture, the fearsome reputations of witches clash with comical representations of them – they are not powerful enough to change the landscape, but are easily able to conjure up a way of spiting an unfaithful lover.

Like the Sandersons, these Roman witches use their powers to seduce lovers, spite enemies and stay young. As in Hollywood productions, both Horace and Apuleius caricature the grotesqueness and pettiness of witches – in stark contrast to the power and influence of witches that was to develop in medieval times.

In Horace and Apuleius’s works, witches were figures of fun. Interestingly life imitated art for Apuleius when he himself was tried for witchcraft. Apuleius’ Apologia details his defence against charges that he bewitched his older, wealthier wife Pudentilla. This suggests that Roman audiences could laugh at witches as comic characters even as trials for witchcraft were still happening.

Ultimately, fictitious witches have always reflected transgressive women, whether they are threatening femme fatales such as Ovid’s Medea, or hilarious hags like Horaces’ Canidia. Both of these interpretations persist in popular culture to this day.