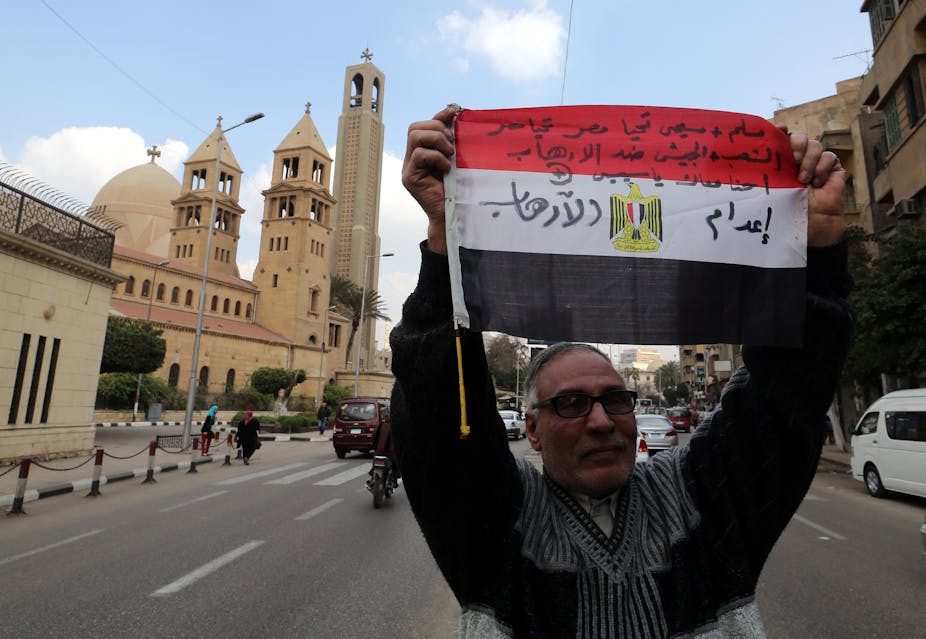

On February 16, Egypt bombed Islamic State (IS) targets in the militant-controlled Libyan city of Derna, in response to the beheading of 21 Egyptian workers. The speed with which this unprecedented military intervention was mounted across the Libyan border reflects the increasingly tense situation between the two countries – a problem that has preoccupied the government of Abdul Fattah al-Sisi for a long time.

It also shows how, in a climate of suspicion and fear, al-Sisi is prepared to do almost anything to stave off the nightmare of cross-border Islamic terrorism.

Stability at all costs

Above all else, al-Sisi’s priorities are territorial integrity, anti-Islamism, and anti-militancy. He has been threatening military intervention in Libya for months, concerned that the violence there could spill over into Egypt. There have already been hundreds of attacks on Egyptian border security forces. The strikes targeted militant camps, training grounds and weapons-storage facilities in Libya, where the lack of a strong government and institutions has opened up fertile ground for the proliferation of Islamist insurgent groups.

This is a major challenge for al-Sisi, a former chief of Egypt’s armed forces who seized control of the country in one of its most chaotic moments. His domestic concerns – dealing with the threats of Islamism, terrorism and instability – are closely tied to his foreign policy, which is both following trends that have held for decades and adapting as demanded by circumstances.

Since the Arab Spring, US-Egypt relations have been strained to say the least. That means al-Sisi has had to lean more heavily on other Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, for financial and military support. Those countries are also fighting long battles against both Islamic State and the Muslim Brotherhood and its offshoots and they need Egypt to succeed along with them.

As a result, al-Sisi’s “doctrine” has morphed into a fierce dedication to regional stability and the status quo.

All of the above

Egypt’s modern foreign policy has also been marked by a consistent hostility towards Hamas and an openness to working with Israel. There are reasons for that: apart from the brief interlude of Morsi’s presidency, Egyptian politics have always had an anti-Islamist bent.

Successive Egyptian governments have seen Hamas as directly responsible for Egypt’s instability and insecurity, as it is after all a direct offshoot of the long-outlawed Muslim Brotherhood.

Now, in what seems to have become a recurring theme, recent events and attacks on Egyptian security forces in the Sinai desert – allegedly carried out by Islamist groups affiliated to IS – have provoked yet another unprecedented foreign policy decision from al-Sisi’s government: the closure of the Rafah border crossing.

The crossing has historically served as a passage for both weapons and militants into Gaza. It is now to be permanently shut and replaced with a military buffer zone 1km wide and 13km long. This decision has caused the forced evacuation of more than 2,000 Egyptian families from the area.

That hard-line approach reflects al-Sisi’s concern over insecurity spilling over the borders and confirms Egypt’s regional role as one of Israel’s closest allies – even as Cairo’s ties with other Gulf nations are being strengthened.

Since al-Sisi’s supporters and enemies alike agree that security in Egypt is worryingly poor, the fate of efforts to stabilise the borders could have substantial repercussions on the country’s domestic politics. The same effect is apparent in recent decisions on how to tackle IS.

As he tries to stabilise and protect his country, al-Sisi is distancing himself both from historical sectarian allies and from the Sunni-Shia geopolitical agenda that has animated the Middle East for decades. Instead, he is demonstrating a commitment to the conservation of regional stability that overrides old sectarian allegiances, simultaneously pursuing diplomatic co-operation both with Egypt’s long-standing rival Iran and its allies in Syria and Iraq.

At the same time, he is not afraid to take the lead where he deems it necessary: he has now called for a UN resolution allowing international military intervention in Libya and has purchased 24 advanced fighter jets from France.

Ultimately, al-Sisi’s commitment to securing Egypt’s borders is turning the country into a remarkably innovative and assertive foreign policy presence. Whether it will do anything to stabilise an increasingly unbalanced and chaotic Middle East, to say nothing of Egypt’s own restive domestic politics, remains to be seen.