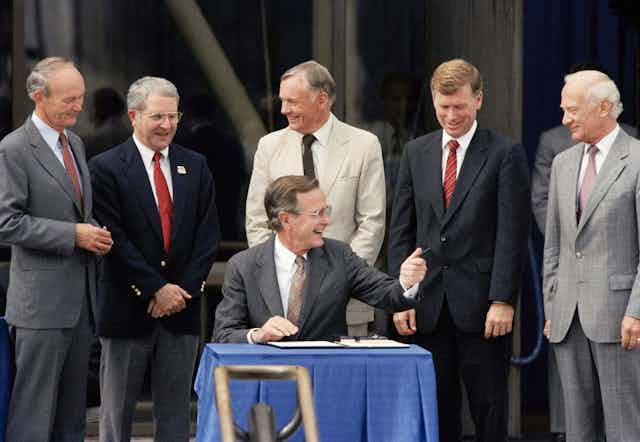

On July 20, 1989, the 20th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, President George H. W. Bush stood on the steps of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. and, backed by the Apollo 11 crew, announced his new Space Exploration Initiative (SEI). He believed that this new program would put America on a track to return to the moon and make an eventual push to Mars.

“The time has come to look beyond brief encounters. We must commit ourselves anew to a sustained program of manned exploration of the solar system and, yes, the permanent settlement of space,” he said.

As a political scientist who seeks to understand space exploration’s place in the political process, I approach space policy with an appreciation of the political hurdles high-cost, long-term and technologically advanced policies face. My research has shown that policy change both in general and in space policy, is often hard to come by, something exemplified by the Bush administration.

Among Bush’s many political accomplishments, few recall SEI, probably because it was largely panned immediately following its announcement. However, Bush’s presidency came at a key turning point in NASA’s history and ultimately contributed to the success of the International Space Station, NASA leadership and today’s space policy. As the country mourns his passing and assesses his legacy, space should rightly be included on Bush’s list of accomplishments.

Vice presidential years

While presidents are usually the most closely associated with the American space program, vice presidents often play a vital role. As Ronald Reagan’s vice president, Bush was intimately involved with NASA throughout the 1980s. He visited the astronauts who crewed the second shuttle mission in 1981, commiserating with them about their mission which had been shortened. And, he often enjoyed speaking to astronauts mid-flight.

In a 1985 White House speech, Bush announced that teacher Christa McAuliffe would fly aboard the ill-fated Challenger. In the wake of the disaster, Reagan dispatched Bush to meet with the families at Kennedy Space Center given his ties to the mission. After a private meeting with the families, Bush addressed NASA employees at Kennedy and pledged the space program would go forward, a promise he kept as president.

SEI and the Space Station

Shortly after taking office, the Bush administration sought to provide a vision for NASA. Bush reinstated the National Space Council and, allied with Vice President Dan Quayle, developed the SEI to coincide with the anniversary of Apollo 11. With less than six months between Bush’s inauguration and July 1989, there was little time to flesh out specific deadlines or funding sources. What resulted was a vague promise to build a planned space station in the next decade, return to the moon and venture onto Mars. With this lack of specifics, the SEI aroused immediate suspicion from both NASA and Congress.

The SEI faced a number of political hurdles upon its announcement. But 90 days later, opposition to SEI grew exponentially when a follow-up analysis of the initiative revealed a 30-year plan with a half-a-trillion-dollar price tag. Then the discovery of a flawed lens on the Hubble Space Telescope after its launch in 1990, the massive cost overruns on what was then called Space Station Freedom (the program had grown from $8 billion in 1984 to $40 billion in 1992), and an economic downturn all combined to threaten overall funding for NASA. While Bush lobbied aggressively for the SEI, the program failed to receive support and was largely shelved.

But what emerged from the SEI was still significant. When Congress threatened to cut funding to and essentially end the nascent space station, the Bush administration pushed to save it. Although NASA’s overall funding was cut, Bush’s support and the rationale behind the SEI gave the space station enough continued importance that Congress restored $200 billion to the space station budget.

Finally, the moon to Mars framework has remained relevant in human spaceflight. George W. Bush’s Vision for Space Exploration, proposed in 2004, retained the same goals but grounded it with a clear timetable and budget. Proposing a moon-Mars program is nothing revolutionary, but the SEI kept the idea of an expansive exploration agenda alive.

Leadership choices

One of most significant impacts a president can have on a bureaucracy is choice of agency leadership. In that area, Bush succeeded in placing his stamp on NASA for years to come. Bush’s first choice for NASA administrator, former astronaut Richard Truly, was out of his depth politically. Truly did not support SEI and other space initiatives and was fired in 1991, partially at Vice President Quayle’s urging.

Bush’s choice to replace Truly was Dan Goldin, who became NASA’s longest serving administrator, staying on through the Clinton administration. Characterized as one of the most influential administrators in NASA history, Goldin took on the job of finding more support for the space station. He convinced Clinton that it could be useful in foreign policy. As a result, Clinton used the space station as a tool to ease Russia’s transition to a democratic state. The International Space Station was launched in 1998 due in large part to the support from the Bush administration. Having hosted 232 people from 18 countries, the ISS recently celebrated its 20th anniversary.

More importantly, Goldin initiated a program known as “faster, better, cheaper” (FBC), which required NASA to do more with less by bumping up the number of lower cost missions. Although this mindset led to several high-profile failures, including a crashed Mars probe, Goldin successfully shifted NASA onto a more sustainable political footing. As a result, Bush’s choice of NASA leadership was crucial to the direction and success of American space exploration.

Bush’s legacy

Space exploration is a difficult policy field. It requires long-term planning, consistent funding and visionary leadership, any one of which is difficult to achieve. Further, space policy is incredibly sensitive to overall economic dynamics, making it susceptible to continual budget cuts.

One can certainly debate the benefits of the International Space Station or the scientific value of human space exploration but, for better or for worse, NASA is the agency it is today because of the choices George H.W. Bush made as president. Ad astra, President Bush.