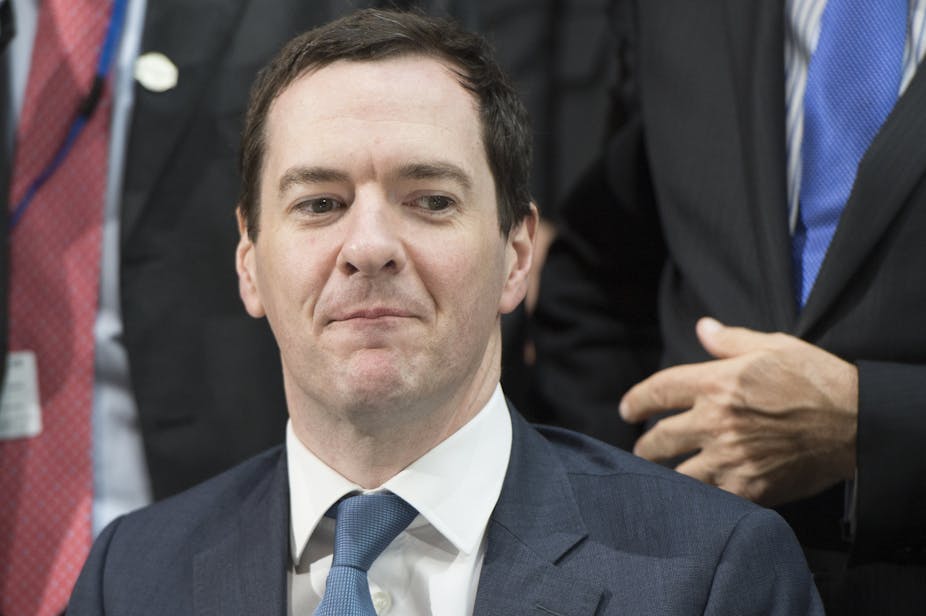

Critics have been lining up to take shots at the London Evening Standard – and its editor George Osborne – since allegations emerged recently in Open Democracy that the newspaper had been selling positive news coverage to major companies including Uber and Google.

The Standard has strenuously denied the claims that the newspaper had struck commercial deals that go beyond the practice – common among newspapers – of publishing “branded editorial” paid for by companies and clearly marked as such. Jon O’Donnell, group commercial director at ESI Media, called the allegations “a wildly misunderstood interpretation” of their plans and stressed that commercial content in the newspaper and online would always be labelled as such.

The Open Democracy story, by reporter James Cusick, was accompanied by a slide, said to be from an Evening Standard sales presentation, suggesting that – on the contrary – companies opting into the promotional deal would not only be associated with clearly marked promotional material but would also be offered “money-can’t-buy” opportunities for promotion because the campaigns would be expected “to generate numerous news stories” as well as comment pieces.

It is this bullet-pointed item on the bill of sale that sparked outrage across the mainstream press (with articles in both The Guardian and The Times) and a ripple of shock in the twittersphere because of its implication that companies paying £500,000 for a sponsorship deal would also buy positive news coverage. Labour’s shadow culture secretary, Tom Watson, tweeted thus:

Blurred lines

In a world in which the funding model of every major news organisation has been seriously damaged by the flight of advertising cash to internet platforms, promotional content (also called advertorials, native advertising or sponsored content) has become a key source of much needed funding. Indeed nearly three-quarters of online publishers were using some form of native advertising by the middle of 2013.

But while advertisers believe that the most valuable promotion is positive press coverage, they are banned from paying for editorial endorsement and any suggestion that this is happening would not only put them in breach of the Advertising Standards Authority rules but would also impact their credibility as a trusted news source. So promotional content is designed to offer brands something that looks like journalism without crossing the line into paid-for editorial.

Vice has been a leader in the concept of native content and prides itself on providing advertisers with the expertise to make promotional material with the same feel and look as their editorial. The company recently won the Digiday awards for a multimedia project sponsored by Channel N°5 L’Eau fragrance.

The Guardian has similar deals. A fashion site called “The Chain” is produced in association with Google – and the company has established a “commercial features desk” where freelance journalists are commissioned to write paid-for content.

Both these companies clearly mark their sponsored content as they are obliged to, but they are also concerned about their reputation for independence. As The Guardian makes clear: “This content is produced by commercial departments and does not involve GNM staff journalists.” Nevertheless, the separation of editorial and advertising is increasingly blurred, as a Digiday story about The Guardian in January 2018 made clear:

Dozens of cross-department huddles occur each month, with people from commercial, editorial, product, marketing, engineering and user experience meeting with a set problem to solve.

It is this fuzziness that worries journalists. In 2015, journalist Peter Oborne resigned from his position as chief political commentator of the Telegraph because he believed that a deal with the bank, HSBC, had compromised the newspaper’s independence. He said then:

The coverage of HSBC in Britain’s Telegraph is a fraud on its readers. If major newspapers allow corporations to influence their content for fear of losing advertising revenue, democracy itself is in peril.

Problem for democracy

Osborne, the Standard’s editor is also the former chancellor of the exchequer. He is a man with a far greater understanding of commerce than of journalism – and he appears to have previously crossed the line in a similar way. Another Open Democracy article, published in February 2018, revealed a lucrative deal with the chemical company Syngenta over a series of articles on the future of food. The articles omitted mention of Syngenta’s lobbying of the government over post-Brexit rules on the use of genetically modified seeds and side-stepped discussion of legal challenges to Syngenta in the United States.

While sponsorship from perfume or sports shoes may not appear to compromise editorial integrity, the rising power of the commercial director has other, more subtle, effects. As one Evening Standard journalist told me ruefully the day the latest Open Democracy story was published:

While sponsorship deals pay us to cover certain stories there are other stories that no one will pay us to cover and they don’t get space.

The problem is not merely a matter of journalistic ethics and integrity, it is about the survival of journalism as a contributor to liberal democracy. For most of the past century, news production has been almost entirely supported by money from advertising. Now the life blood of journalism has been diverted and is being pumped into the platforms at the heart of digital communications. As Google siphons off the money, there is something particularly depressing at the sight of news organisations going cap-in-hand to beg for a payment of £500,000 and promising to chuck in some favourable press coverage as part of the bargain.

Read more: Fake news week: three stories that reveal the extreme pressure journalism is now under

The last thing that the news industry needs is a moratorium on criticism of the digital platforms whose under-regulated, globe-striding companies have already demonstrated their ability to wriggle out of the few obligations that do apply to them. Journalism, democracy and citizens need a fourth estate that is not in hock to the very companies it needs to be holding to account. Instead of getting into bed with Google and Uber, news companies would be better advised to campaign for their regulation, in the public interest.