Kurt Cobain was the messiah of my generation, the monumental talent who saved rock from the mediocrity of 1980s cock rock and hair metal. But behind his public eminence stalked a personal hell of addiction and depression. When he killed himself at 27, he left a note quoting a Neil Young lyric: “It’s better to burn out, than to fade away.”

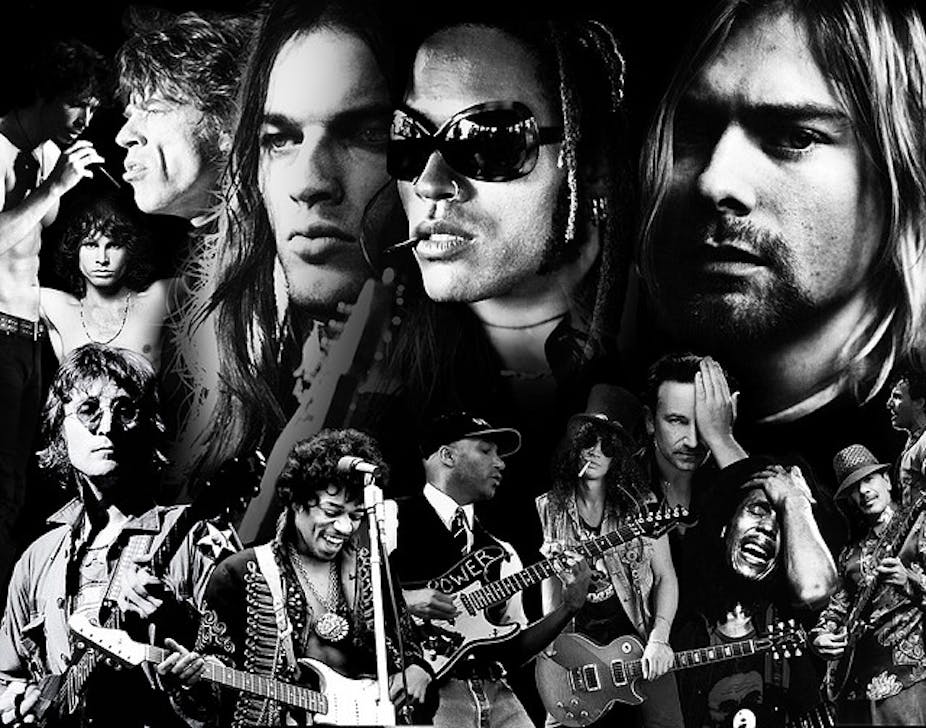

Music greats like Cobain have a nasty tendency to die young. Blues pioneer Robert Johnson, guitar deity Jimi Hendrix, Rolling Stone Brian Jones, and singers Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison are among the many greats who died at 27.

And there’s nothing special about 27 either. Buddy Holly, Bon Scott, John Bonham, Keith Moon and many others never made it out of their early 30s.

Live fast, die young

Dying young or fading away do seem to be two sides of the same coin. Heads you die young, tails you live long enough to succumb to dementia and decrepitude.

The fast-living rock ’n’ roll lifestyle accelerates both, but everybody either dies young or dies slowly. Rock is really just life, amplified, and turned up to 11.

In Sex, Genes & Rock ’n’ Roll: How Evolution has Shaped the Modern World, I devote several chapters to the evolutionary origins and consequences of music.

Music is the most elaborate and sublime courtship signal that ever evolved. And if we are to understand why great musicians are so prone to an early grave, we first need to understand courtship and its costs.

Sing more, get more

Complex cultural phenomena seldom have single origins, but courtship sits right at the heart of our capacity to make and enjoy music.

In most, if not all societies, women and men get to know each other better by listening and dancing to music. From the evening serenades of 18th century Italy to the Saturday night love markets of northern Vietnam, young men and women often sing to one another to woo and win affection.

But the link between music and mating success is strongest for musicians. By the very act of playing, a musician breaks the ice with a pool of possible mates. The better the music, the bigger that pool.

But the musician also signals his or her suitability as a mate. It takes talent, intelligence and persistence to master an instrument, and more than that to write music and lyrics that ring true. The better the musician, the more audience members will find him or her attractive.

Or as Keith Richards put it “Six months ago I couldn’t get laid; I’d have had to pay for it. One minute no chick in the world. No fucking way… and the next they’re sniffing around.”

Chicks for free? I don’t think so.

In evolution, as in life, nothing worthwhile comes for free. Spend a summer evening in the Australian bush and you are sure to hear male black field crickets calling away.

By rubbing his wings together several times a second for hours on end, a male cricket advertises where he is. Any females in the area who are ready to mate will walk toward the male, locating him by his call alone. So the more a male calls the more females he mates with.

But calling exacts a cost. The muscles that drive those noisy wings wings burn energy, and calling also advertises a male’s position to spiders, bats and parasitic flies, raising the danger to males that call.

The most attractive and successful crickets - the males that leave the most offspring in each generation – live faster, call more and die younger than their quieter brothers.

What about us?

Human reproduction is just as costly. Women have always endured a real chance of dying in childbirth, the burden of carrying a baby to term and the time and energy invested in breastfeeding. Today, as for most of human history, the longest-lived women are most likely to have had few or no children.

The costs of finding and attracting mates and vanquishing competitors are harder to observe directly, but every bit as real.

Wealthier men enjoy considerable advantage over poorer men in attracting partners. So less well-off young men compete furiously to elevate their status and material wealth in order to have a chance of winning a mate.

And the bigger the differences in wealth, status and mating opportunities within a society, the more intensely young men compete.

As Eastern Europe transitioned to market-based economies in the early 1990s, new economic opportunities and inequalities in income and status exploded.

Young men in particular took on the stress and risks involved in striving for new sources of wealth, and male mortality escalated.

Get rich or die trying

Musical greats have probably always been at the sharp end of the trade-off between reproduction and mortality. Mozart was a notorious pants man, and he worked so hard that his health failed and died at 35. But even he enjoyed only local fame during his lifetime.

Twentieth century technologies, like the gramophone, radio and television made it possible for a few lucky and talented musicians to be world famous and unimaginably wealthy while still young.

And this wrought record inequalities between musicians in earning power and groupie adulation.

Along came rock, a musical form so simple that it could be learned without formal training. Armed with only three chords and the truth, a young person could rise in a few short years from poverty to phenomenal wealth, fame and sexual attractiveness.

This is the story of Ray Charles, Johnny Cash, Elvis, The Beatles, Keith Richards, Bob Marley, AC/DC and many others.

It’s a story that the most gangsta forms of rap have perfected; from Dr Dre to 50 Cent: rap is a struggle, a battle, a furious jostling for status, respect, wealth and, ultimately, for sex.

Rock and rap draw their creative fire from the reckless bravado and relentless striving for fame, fortune and gratuitous sex with groupies.

It’s far from the only theme, but it is an important one that embodies an equally important evolutionary principle: the future isn’t worth as much as the present.

Or as Jim Morrison put it, “I don’t know what’s gonna happen, man, but I wanna have my kicks before the whole shithouse goes up in flames.”

Musicians pay a heavy price for their success. The frantic striving of younger rockers, rappers, blues musicians and many other entertainers requires that they discount the future.

They work a hard day’s night, live on the edge and many are prepared only to sleep when they’re dead. They also use drugs, abuse booze, drive their cars too fast, carry weapons and escalate deadly rivalries more than average people of the same age.

As a result they are almost twice as likely to die young as other people of the same age born into the same circumstances.

You can read a review of Sex, Genes and Rock and Roll here.