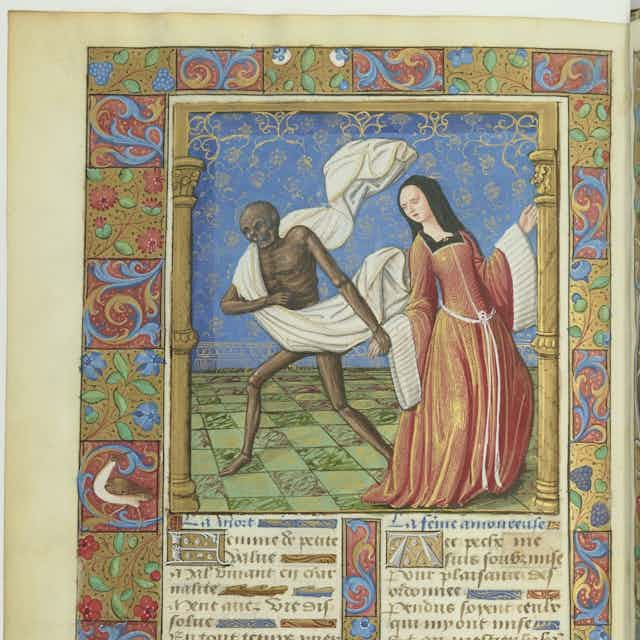

In medieval Europe, views of women could often be summed up in two words: sinner or saint.

As a historian of the Middle Ages, I teach a course entitled Between Eve and Mary: the two biblical figures who sum up this binary view of half of humanity. In the Bible’s telling, Eve got humans expelled from the Garden of Eden, unable to resist biting into the forbidden fruit. Mary, meanwhile, conceived the Son of God without human intercourse.

Either way, they’re daunting models – and either way, patriarchy considered women in need of protection and control. But how can we know what medieval women thought? Did they really accept this vision of themselves?

I do not believe that we can totally understand someone who lived and died hundreds of years ago. However, we can try to somewhat reconstruct their frame of mind with the resources we have available.

Few documents that survive from medieval Europe were written by women or even dictated by women. Those that do are often formulaic, full of legal and religious language. Yet the wills and censuses that survive, and which I study, open a window into their lives and minds, even if not produced by women’s hands. These documents suggest that medieval women had at least some form of empowerment to define their lives – and deaths.

A centuries-old census

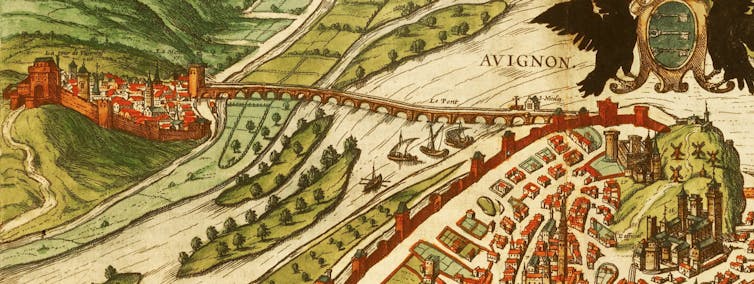

In 1371, the city of Avignon, in present-day France, organized a census. The resulting document is ripe with the names of more than 3,820 heads of household. Of these, 563 were female – women who were in charge of their own household and did not shy away from declaring it publicly.

These were not women of high social status but individuals scarcely remembered by history, who left only traces in these administrative documents. One-fifth of them declared an occupation, including both single and married women: from unskilled laborer or handmaid to innkeeper, bookseller or stonecutter.

Nearly 50% of the women declared a place of origin. The majority came from around Avignon and other parts of southern France, but some 30% came from what is now northern France, southwest Germany and Italy.

The majority of ladies who arrived from faraway regions arrived alone, suggesting medieval women were not always necessarily “stuck” at home under the domination of a father, brother, cousin, uncle or husband. Even if they wound up that way, they seemed to show some guts by leaving in the first place.

New cities, new lives

In cities like Avignon, with a large proportion of immigrants, long-lasting lineages disappeared. As historian Jacques Chiffoleau has suggested, most late medieval Avignonese were “orphans” who lacked extended family networks in their new surroundings – and this was reflected in the culture.

Since the 12th century, women in the south of France had been considered “sui iuris” – capable of managing their own legal affairs – if they were not under a father or husband’s control. They could dispose of their own possessions and distribute them at will, both before and after death. Married daughters’ dowries often prevented them from inheriting parents’ property, but they could when no male descendants could be found.

In the late Middle Ages, women’s legal rights expanded as urbanization and immigration changed social relationships. They could become legal guardians of their children. What’s more, judging by women’s testaments, widows and older daughters did make legal decisions of their own without the “required” male guardianship.

In addition, married women could make legally binding decisions as long as their husbands were present with them in front of a notary. Although husbands were technically considered their wives’ “guardians,” they could declare them legally free of guardianship. Wives would then be allowed to name their witnesses, appoint their universal heir and list donations and bequests to individuals and the church, which they hoped would save their soul.

Speaking beyond the grave

European archives literally overflow with legal documents that are awaiting discovery in musty boxes. What is lacking is a new generation of historians who can analyze them and paleographers who can read the handwriting.

Everyone high and low used notaries’ services for contractual forms, from an engagement and marriage to the sale of property, business transactions and donations. In this mass of documentation, wills provide a refreshing perspective into medieval women’s agency and emotions as they contemplated the end of their lives.

In the 60 or so women’s testaments kept in Avignon, women named where and with whom they wanted to be buried, often choosing their children or parents over their husbands. They named which charities, religious orders, hospitals for the poor, parishes and nunneries would benefit from their generosity, including bequests for repairs on Avignon’s famous bridge.

These women may have dictated their last wishes lying in bed, waiting for death, with the notary guiding their decisions. Still, given the things they dictated – donations for the dowries of poor girls, for their relatives and friends, to have their names remembered in Catholic Masses for the dead – I would argue that we are hearing their own voices.

Rosaries, repairs and furs

In 1354, Gassende Raynaud of Aix asked to be buried with her sister, Almuseta. She left a house to her friend Aysseline, while Douce Raynaud – who may have been another sister – received six dishes, six pitchers, two platters, a pewter jug, a cauldron, her best cooking pot, a cloak of fur with muslin, a big blanket, two large sheets, her best bodice, a little coffer, and all the mending thread and hemp that she possessed. She left a coffer, a copper warmer, the best trivet of the house and four new sheets to her friend Alasacia Boete.

Gassende’s generosity didn’t stop there. Jacobeta, Alasacia’s daughter, received a rosary of amber; Georgiana, Alasacia’s daughter-in-law, a bodice; and Marita, Alasacia’s granddaughter, a tunic. To her friend Alasacia Guillaume, Gassende left the unusual gift of a portable altar for prayers and an embroidered blanket. To Dulcie Marine, she bequeathed a choir book called an antiphonary and the best of her cloaks or furs.

In another Avignon will, written in 1317, Barthélemie Tortose made bequests to several Dominican friars, including her brother. She left funds to the prior of the order, her brother’s supervisor: perhaps rewarding the “boss” in order to keep her brother in his favor. She provided for charities and repairs for two bridges over the violent Rhône River, but also substantial support to provide food and clothing to all nuns’ convents of the city.

More especially, she supported her female kin, such as leaving rental income to her niece, a Benedictine nun. She then requested that her clothes be cut into habits for nuns and liturgical garments.

We can get a glimpse at just how personal these bequests were: These women assumed that what they had touched, or what had touched their skin, would also touch another’s. Most of all, they expected that their possessions would transmit their memory, their existence, their identity.

What’s more, medieval women could be pretty radical.

At least 10 women whose wills I’ve read asked to be buried in monks’ cassocks, including Guimona Rubastenqui. Widow of an Avignon fishmonger – usually a profitable occupation – she requested that Carmelite brother Johannes Aymerici give her one of his old habits, for which she paid him six florins.

Asserting their will

So, what do we make of all this?

It is impossible to completely reconstruct how people lived, loved and died centuries ago. I have spent my adult life thinking “medieval,” yet know I will never get there. But we certainly have clues – and what I call an educated intuition.

By modern standards, these women faced real limits on their power and independence. However, I have argued that they “freed” themselves at death – their wills presenting a rare opportunity to make personal legal decisions and to live on in written records.

Medieval women could have agency. Not all of them, not all the time. But this small sample shows that they could choose whom they wanted to reward and whom they could help.

As for the burial in men’s garb, I have no way of knowing whether their wishes were followed. But from my perspective, there is something extremely satisfying in knowing that at least they tried.