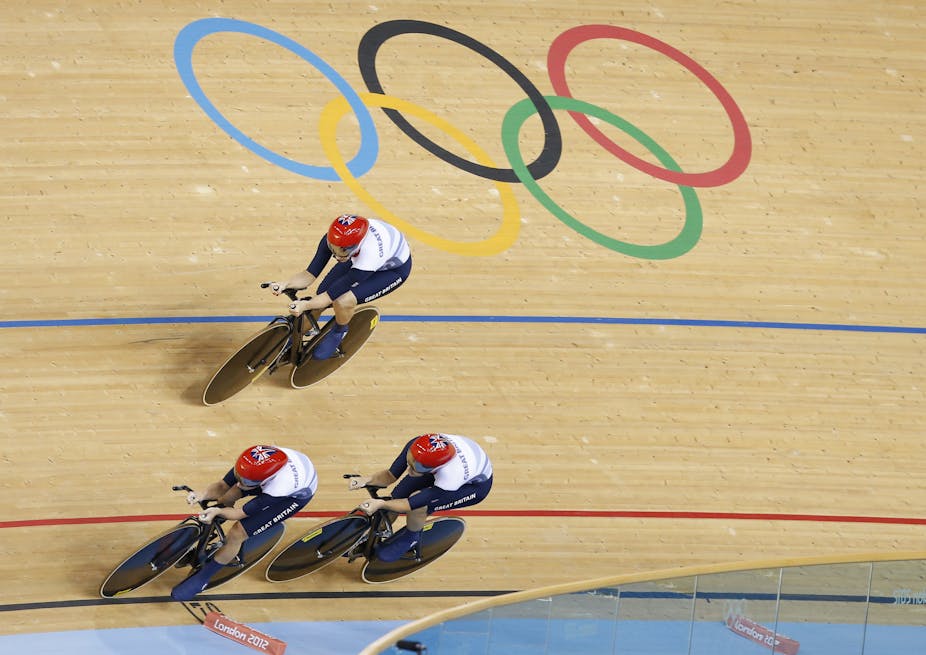

London’s Olympic Velodrome is opening to the public for the first time. The scene of great triumph for Team GB in the London 2012 Olympics, it should welcome droves of budding cyclists who hope to one day follow in the pedals of gold medallists like Sir Chris Hoy, Victoria Pendleton and Laura Trott.

The velodrome’s re-opening forms part of the wider Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park redevelopment, which promises integrated spaces, affordable housing options, inclusive design and active lifestyle opportunities that would appeal to all walks. Yet, how will these benefits be realised and who will become connected (or disconnected) to these new spaces?

London’s Olympic legacy is often spoken of in the vague, but neutral language of “the public good”. Whether that is in terms of the creation of new facilities, greater sport participation or economic benefits, it’s often assumed that these benefits will be universally applicable to all citizens. But a closer look at the way they are set up and marketed betrays certain gender and class-based assumptions.

Open but exclusive

Take facilities like the velodrome – the Lee Valley VeloPark – that opens to the public today. It opens on a user-pays basis to encourage active community participation. But it could be a costly outing for keen adults (and families) who want to try a range of disciplines, with taster sessions for the track cycling at £30, road circuit, mountain bike trails and the re-designed Olympic BMX track all at £15 a pop.

While women are offered several specific taster sessions there are few images of female cyclists around the VeloPark, despite the Olympic and Paralympic role models of 2012 such as Victoria Pendleton and Sarah Storey. This lack of inclusiveness betrays how many of the London 2012 legacies have been redesigned in gendered ways that largely ignore the inequities different women face in sport or everyday life.

Gendered assumptions are inherent in the spatial and commercial refashioning of London. For example, advertisements for the new Glasshouse Gardens development that overlook the Olympic Park predominantly feature women walking, shopping, talking, eating with friends, partners and children. Similarly, promotional brochures for the newly converted rental properties at East Village E20, formerly the Olympic Village, uses imagery that creates a brand almost exclusively marketed towards (middle-class) young women. These gender images portray consumption-focused lifestyles where women are assumed to have endless opportunities to enjoy these new urban spaces.

Safe and secure enclaves

Policy makers, urban developers and marketers are promoting the post-Olympic areas of urban renewal as “safe and secure” enclaves, offering desirable qualities for responsible, middle-class, new urban living. Shopping, lattes, leisurely lunches and dinners at Jamie’s Italian are to be enjoyed within close proximity. Yet, distance is maintained from existing communities, limiting the scope for social inclusion.

In accordance with Greater London’s development strategy, the idea is that crime will be eradicated through the design of new areas. Their gentrification creates public spaces that are overlooked by private apartments. The London Legacy Development Corporation who are in charge of transforming the Olympic Park have an urban planning strategy that is meant to reduce feelings of isolation and increase feelings of safety. Features of inclusive design are said to be particularly important for those most vulnerable to “hate crime” such as women, and who are concerned about freedom of movement at night.

Despite the policy of inclusive design the spatial organisation reflects a suspicion of “others” who may pose a threat to the safety of new residents. The association between women and fear is contrasted by the marketing of “safe living” choices in the new urban village, while the social issues connecting crime and inequality are situated beyond the gate. Separate entrances and gates clearly mark the boundaries between public and private territories and demarcate who belongs and who is excluded, despite the rhetoric of mixed private and public space.

Privatised and private

With the private sector investing heavily in London 2012’s urban renewal legacy, further discussions of how the space is privatised, as well as how these newly designed areas are used, managed and controlled is all the more important.

LandProp, the residential development and investment arm of IKEA, is solely responsible for the creation of the new Strand East community, a mixed-use neighbourhood emerging as one of the many products of post-London 2012 gentrification. IKEA’s involvement with the design and redevelopment of residential, commercial and leisure facilities surrounding the Olympic park, prompts a call to consider whether these developments are purposefully constructed for the same middle-class consumer target market that frequent their familiar department stores.

This reconstitution of urban space by private companies has become representative of an undemocratic approach towards the way our cities are governed. This approach welcomes those with the means into a privately owned and privately policed section of the nation’s capital. But those lacking them are not included.

This kind of approach to urban planning presents a rather disturbing vision of London’s cityscape. The newly developed pockets of regeneration seem to be following a model of progression that moves further away from the promise of inclusivity outlined by the London 2012 Olympic legacy.

The way this vision is emerging in reality should be challenged through a review of the policy process, marketing strategies and built environment that currently encourage the encroachment of corporations. Plus, given the gendered nature of the legacy, questions arise about the way women become invisible within certain sporting contexts yet are made visible in other spheres of consumption. The visible, public projection of women in the Olympic legacy should not just play into stereotypes that suit its growing privatisation and targets a narrowly defined minority.