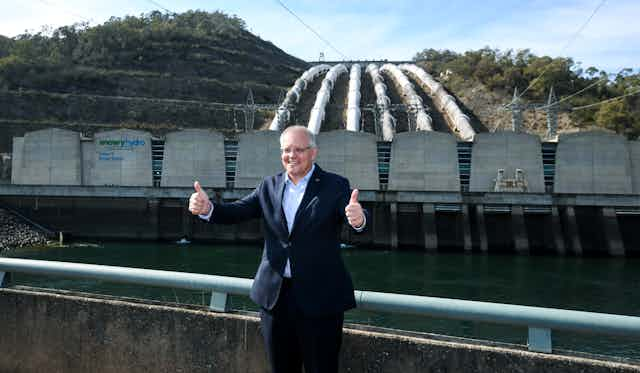

The Morrison government today announced it’s building a new gas power plant in the Hunter Valley, committing up to A$600 million for the government-owned corporation Snowy Hydro to construct the project.

Critics argue the plant is inconsistent with the latest climate science. And a new report by the International Energy Agency has warned no new fossil fuel projects should be funded if we’re to avoid catastrophic climate change.

The move is also inconsistent with research showing government-owned companies can help drive clean energy innovation. Such companies are often branded as uncompetitive, stuck in the past and unable to innovate. But in fact, they’re sometimes better suited than private firms to take investment risks and test speculative technologies.

And if the investments are successful, taxpayers, the private sector and consumers share the benefits.

Lead, not limit

Federal energy minister Angus Taylor announced the funding on Wednesday. He said the 660-megawatt open-cycle gas turbine at Kurri Kurri will “create jobs, keep energy prices low, keep the lights on and help reduce emissions”.

Experts insist the plan doesn’t stack up economically and may operate at less than 2% capacity.

But missing from the public debate is the question of how government-owned companies such as Snowy Hydro might be used to accelerate the clean energy transition.

Australian governments (of all persuasions) have not often used the companies they own to lead in clean energy innovation. Many, such as Hydro Tasmania, still rely on decades-old hydroelectric technologies. And others, such as Queensland’s Stanwell Corporation and Western Australia’s Synergy, rely heavily on older coal and gas assets.

Asking Snowy Hydro to build a gas-fired power plant is yet another example – but it needn’t be this way.

Read more: A single mega-project exposes the Morrison government's gas plan as staggering folly

The burning question

Globally, more than 60% of electricity comes from wholly or partially state-owned companies. In Australia, despite the 20-year trend towards electricity privatisation, government-owned companies remain important power generators.

At the Commonwealth level, Snowy Hydro provides around 20% of capacity to New South Wales and Victoria. And most electricity in Queensland, Tasmania and Western Australia is generated by state government-owned businesses.

But political considerations mean government-owned electricity companies can struggle to navigate the clean energy path.

For example in April this year, the chief executive of Stanwell Corporation, Richard Van Breda, suggested the firm would mothball its coal-powered generators before the end of their technical life, because cheap renewables were driving down power prices.

Queensland’s Labor government was reportedly unhappy with the announcement, fearing voter backlash in coal regions. Breda has since stepped down and Stanwell is reportedly backtracking on its transition plans.

Such examples beg the question: can government-owned companies ever innovate on clean energy? A growing literature in economics, as well as several real-world examples, suggest that under the right conditions, the answer is yes.

Read more: The 1.5℃ global warming limit is not impossible – but without political action it soon will be

Privatised is not always best

Economists have traditionally argued state-owned companies are not good innovators. As the argument goes, the absence of competitive market forces makes them less efficient than their private sector peers.

But recent research by academics and international policy institutions such as the OECD has shown government ownership in the electricity sector can be an asset, not a curse, for achieving technological change.

The reason runs contrary to orthodox economic thinking. While competition can lead to firm efficiency, some economists argue government-owned firms can take greater risks. Without the pressure for market-rate returns to shareholders, government enterprises may be freer to invest in more speculative technologies.

My ongoing research has shown the reality is even more complex. Whether state-owned electric companies can drive clean energy innovation depends a great deal on government interests and corporate governance rules.

For example, consider the New York Power Authority (NYPA) which, like Snowy Hydro, is wholly government owned.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has deliberately sought to use NYPA to decarbonise the state’s electricity grid. The government has managed the company in a way that enables it to take risks on new transmission and generation technologies that investor-owned peers cannot.

For instance, NYPA is investing in advanced sensors and computing systems so it can better manage distributed energy sources such as solar and wind. The technology will also simulate major catastrophic events, including those likely to ensue from climate change.

These investments are likely to contribute to greater grid stability and greater renewables use, benefiting not just NYPA but other electricity generators and ultimately, consumers.

Such innovation is nothing new. Also in the US, the state-owned Sacramento Municipal Utility District built one of the first utility-scale solar projects in the world in 1984.

The way forward

More could be done to ensure Australian government-owned corporations are clean energy catalysts.

Clean energy technologies can struggle to bridge the gap from invention to widespread adoption. Public investment can bring down the price of such technologies or demonstrate their efficacy.

In this regard, government-owned companies could work with private technology firms to invest in technologies in the early stages of development, and which could have significant public benefits. For instance, in 2020, the Western Australian government-owned company Synergy sought to build a 100 megawatt battery with private sector partners.

But many problems facing state-owned companies are the result of ever-changing government policy priorities. The firms should be reformed so they are owned by government, but operated at arm’s length and with other partners. This might better enable clean energy investment without the politics.