Proper “process” might sound like bureaucratic jargon but a prime minister ignores it at his or her peril. Applied to cabinet, it includes making sure ministers have all the facts. Importantly, it requires having present for the discussion all those who should be in the room.

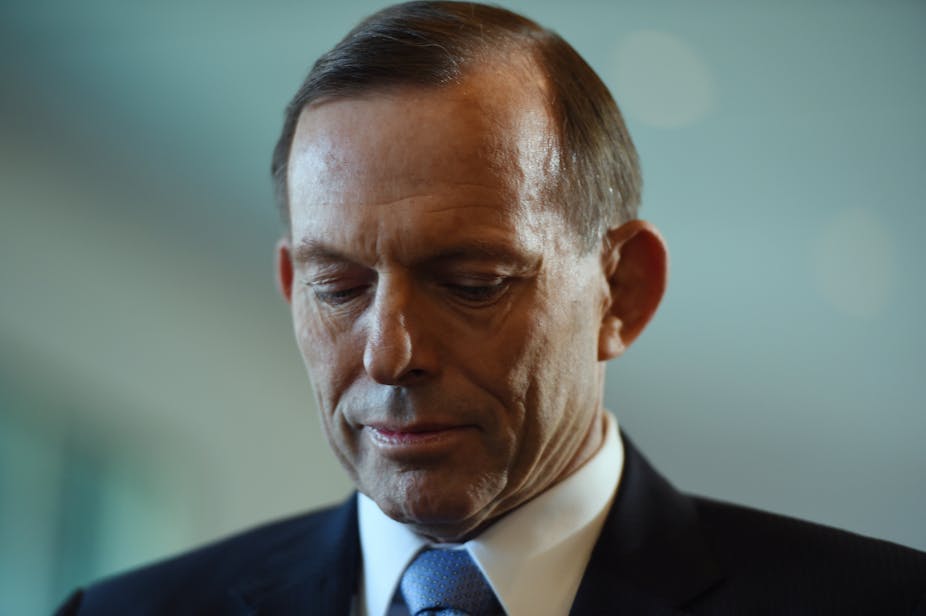

Kevin Rudd had trouble with process, and that was part of his downfall. So too did Tony Abbott this week.

When Communications Minister Malcolm Turnbull was not invited to Monday’s meeting of cabinet’s national security committee, which discussed mandatory metadata retention for two years as part of a national security package, process was trashed, with bad consequences.

Those present, including that self-confessed non tech-head, Abbott, needed Turnbull’s advice. The shambles into which the plan has fallen shows just how much.

Also, Abbott’s apparently ignoring or forgetting to include Turnbull, not a member of the NSC, had all the risks of prodding a porcupine, especially when the decision was leaked before Turnbull got a say in Tuesday’s cabinet. Turnbull might be on the outer, but proper process is all about containing division and dummy spits.

If the government hoped that its national security measures would (at least partly) change the public focus in a way that was positive for it (while Joe Hockey privately tried to cajole crossbenchers on the budget, which is the most pressing game) the mission wasn’t accomplished.

Abbott has managed to unload his unpopular plan to scrap Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act, but the metadata proposal has unleashed a debate that could be almost as damaging and is probably not worth the effort anyway.

As Gillian Triggs, president of the Human Rights Commission, put it rather wryly to a free speech symposium on Thursday: “Seemingly overnight there has been a radical reversal of the public debate, from protection of the right to freedom of speech in our democratic, multicultural society to introduction of a suite of proposals to limit that right in the interests of national security.”

For Attorney-General George Brandis, with responsibilities in both areas – 18C and metadata – it has been a devastating week. Brandis had to cop the “leader’s call” on the RDA. He then gave his fumbling Sky interview on metadata which, replayed endlessly, made him a political laughing stock.

Not happy when on the back foot, Brandis pulled out of the free speech symposium, which had been organised by Human Rights Commissioner Tim Wilson, who was appointed by the government to especially focus on “the liberal human right of free speech”. Wilson was already unhappy about the 18C backdown, before then being stood up by Brandis, whose non-appearance just kept him in the spotlight.

Brandis and Turnbull met on Thursday to try to get some order into the metadata debate, which has become in the public arena more about Big Brother than the terrorist threat.

Speaking to Bloomberg, Turnbull stressed that the types of data that should be retained were still being worked out.

“Unfortunately metadata is a term that can mean different things to different people. So what we want to do is get to the end of consultation [with telcos], conclude the very, very clear parameters of our policy and then explain that and justify it,” he said. “We’re in an iterative process, we’re on a journey and until we get to the end of it, it’s difficult to be much more specific than that.”

The public debate is anything but iterative. As Turnbull said, “the commentary has got ahead of the policy”.

The issue has thrown into the same bed the Greens and the conservative Institute of Public Affairs. “I never thought I would be at one with [Green senator] Scott Ludlam,” IPA executive director John Roskam tells The Conversation.

As the IPA gears up to battle Abbott on metadata it is also delivering a sharp kick at his retreat over 18C, with a $37,000 full page advertisement in Friday’s Australian telling him that it will fight on for the repeal “even if you won’t”.

Roskam says of the metadata plan: “We are very, very opposed. This is very dangerous. Once it happens there is no winding this back. It gives enormous power to the government over people’s privacy. The material will leak. It will be used for purposes not related to anti-terrorism.”

If the government managed to get the proposal up, there would almost certainly have to be with tough new controls, which the security agencies wouldn’t want. Bret Walker, until recently Australia’s national security legislation monitor, this week said he didn’t think collection and storage posed a problem – but access to the metadata should require a warrant (which it doesn’t at the moment).

It’s worth remembering that Labor started along the metadata retention path but abandoned the “journey”. It got all too hard as an election approached.

In the United States, in the wake of the revelations about the collection of data in the document-dump from former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden, there has been a backlash against metadata and arrangements in relation to it are changing.

While it’s too early to make any firm prediction, unless he’s very careful Abbott’s metadata initiative might end up going the same way as the crusade to get rid of 18C.