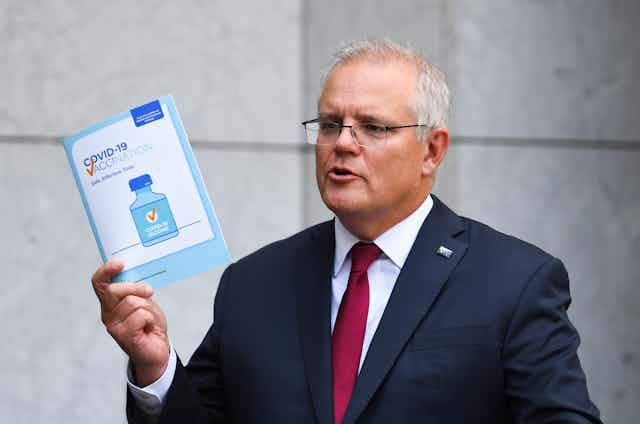

Managing the vaccine rollout and recalibrating the government’s climate policy are vastly different issues but both confront Scott Morrison as major challenges as he settles into the 2021 political year.

Foremost but not entirely, the rollout is about getting right a highly intricate planning and administration exercise. The health and economic consequences of serious bungles could be substantial.

In contrast, foremost but not entirely, shifting climate policy is for Morrison about managing the politics, especially within the Coalition.

Morrison will win points if the vaccine rollout is smooth – though there’d be some discount factor, with people being more likely to mark down failure than mark up success.

If he finally executes the climate policy pivot to embrace the emissions target of net zero by 2050, he will have left less room for Labor at the election – but at the cost of tensions within government ranks and a section of its base.

This week’s COVID case in a Victorian hotel quarantine worker, prompting some tightening of restrictions, and the Perth lockdown underlined how vital the vaccine rollout is.

It won’t be a total, let alone immediate, protection for the community. The efficacy of the vaccines in preventing transmission, as opposed to combatting the illness, remains unclear. But vaccination will be the big gun in the armoury against the virus.

Morrison wants no political distraction from the rollout, as his eventual shutting down of rebel backbencher Craig Kelly showed.

Read more: Scott Morrison gives Craig Kelly the rounds of the kitchen

Unlike with some other aspects of COVID management, in particular quarantine, the federal government has taken ownership of the vaccination effort. So whatever the role of the states, political accountability will be sheeted home to Morrison.

The prime minister is always lecturing ministers and public servants about the importance of “delivery” of services and policies. In earlier days, he’d never have imagined he would face a “delivery” test of this magnitude.

To give the required two doses to everyone aged 16 and over by October, the government’s nominated deadline, will mean administering more than a million jabs a week.

The government is investing several billion dollars in an operation that will involve states and territories, hospitals, doctors, chemists, Aboriginal health services, and a “surge” workforce. Distributing the vaccine to remote areas will be logistically complex.

Despite confident statements from the government about its plan, there is still much detail to be nailed down.

Keeping account of who has received their two shots and – given the newness of the vaccines – making sure any adverse reactions are reported, will require an effective IT tracking system.

Like earlier steps in the fight against COVID, decisions have to be made with imperfect and changing information.

The government has lined up a portfolio of vaccines, with critics debating the mix. It announced on Thursday the acquisition of an extra 10 million doses of the Pfizer one, the first to be rolled out.

With the situation so desperate in many countries, availability and delivery timelines become less certain.

Morrison has put a caveat on his commitment to begin the rollout late this month, saying “the final commencement date will ultimately depend on some of these developments we’re seeing overseas”.

Early recipients will include quarantine, border, aged care and health workers, residents in aged care, older people generally, those with health issues, and Indigenous people over 55.

These cohorts should not be hard to reach. Many of the very elderly will be in facilities; others vulnerable to COVID are likely to be alert to their need for the vaccine.

Some younger people could be less accessible – not because of scepticism about the vaccine, but because they don’t feel under as much threat from COVID and might be disinclined to bother (just as some don’t get flu injections). In its promotion, the government must both reassure the doubters and motivate the laggards.

If the government is in a gallop to prepare the rollout, the PM is creeping when it comes to moving towards the 2050 target of net-zero emissions.

In his latest step this week Morrison said: “Our goal is to reach net-zero emissions as soon as possible, and preferably by 2050.” He’d added the word “preferably” to his formulation.

Climate change was canvassed when Morrison and Joe Biden spoke on Thursday, in their first conversation since the US president’s inauguration.

Biden’s April 22 leaders’ conference on climate will provide a pinch point for Australia.

Asked whether the president had invited him to the summit and, if so, whether he’d go, Morrison gave a vague answer. “There are invitations coming, and we’ll be addressing those once they’re received. We spoke positively about these initiatives and so we look forward to being able to participate.”

There’s no doubt that international pressure, notably Biden’s election, and domestic politics are pushing Morrison towards signing up to the 2050 target later this year.

But as he inches towards the target, critics within the Nationals are making it clear they’ll go all out to prevent him adopting it.

Read more: Australia must vaccinate 200,000 adults a day to meet October target: new modelling

Former Nationals resources minister Matt Canavan says: “I’m dead-set opposed to any commitment to net-zero emissions – because it would wipe out massive farming opportunities and cost thousands of jobs in the mining industry.”

Persuading the Nationals to accept the target would be very difficult. Nationals leader Michael McCormack lacks the political capital to give Morrison much help. At the least, the minor party would want exemptions and trade-offs.

The difficulty with the Nationals is a main reason why it is still up in the air whether Morrison will take the final step.

As the government and opposition rejoin battle, there’s the inevitable speculation about Morrison calling the election this year. The chatter has been fuelled by questions over Anthony Albanese’s leadership, only partly quieted by this week’s Newspoll showing government and opposition 50-50 on a two-party basis.

Morrison has hosed down the early election talk, saying more than once that 2022 is poll year.

Talking up next year and then calling an election this year would be a foolish strategy, and face punishment from voters.

While things can always change, the evidence suggests Morrison means what he says, not least because, by allowing for some slippage, a 2022 poll would ensure time for the vaccine program to be fully rolled out.