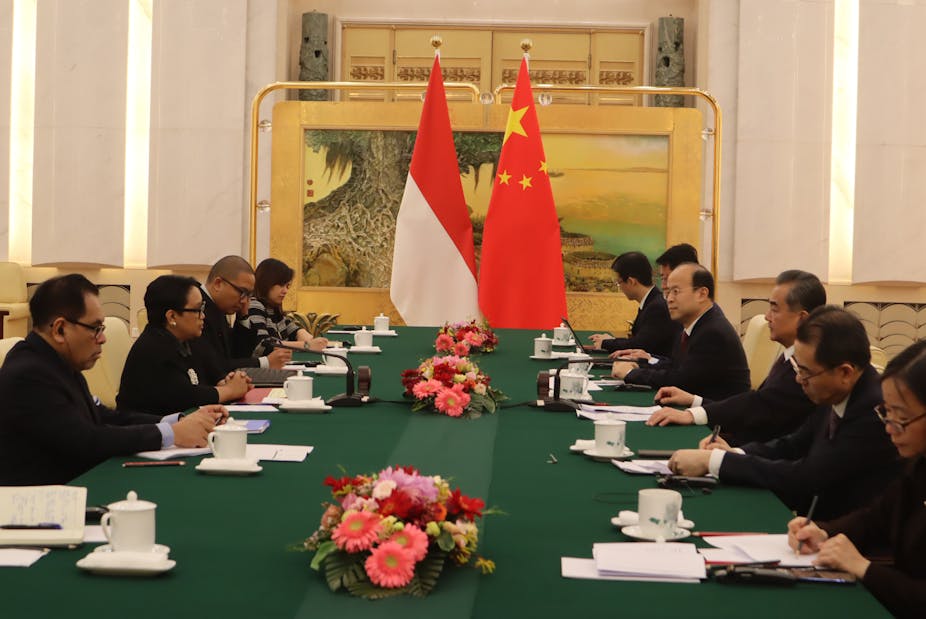

Despite growing anti-China sentiments in Indonesia and the two countries’ unresolved conflicts over the South China Sea, co-operation between the world’s largest exporter and Southeast Asia’s largest economy is set to grow following a meeting of their senior ministers this month.

Indonesia’s co-ordinating minister for maritime affairs and investments, Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, visited his counterpart, China’s foreign affairs minister, Wa Ying, to discuss potential collaborations between their countries amid the pandemic.

One of the main outcomes from the meeting is a decision to make Indonesia the hub for distributing China’s COVID-19 vaccines in the Southeast Asian region.

This co-operation benefits both parties. On one hand, China will have Indonesia with its 270 million population as a testing ground for its COVID-19 vaccines and, at the same time, secure access to the Southeast Asian market.

On the other hand, Indonesia, with the highest number of COVID-19 cases in Southeast Asia, would not only get priority to obtain the vaccine but also gain economic benefits.

This latest deal marks a stronger partnership between the two countries, which might impact Indonesia’s relationship with the US.

Indonesia-China relationship grows stronger

The relationship between Indonesia and China has been growing in the past few years.

Economically, China is Indonesia’s second-biggest source of foreign direct investment (after Singapore) and one of its major trading partners. China was Indonesia’s biggest export destination country in 2019, with a value of US$25.8 billion — around 16.68% of total exports. In the same year, China was the largest source of imports for Indonesia, worth US$44.5 billion, equivalent to almost a third of Indonesia’s total imports.

The two have signed a deal to promote the use of their currencies in their trade agreements, ditching US dollars.

China and Indonesia have also expanded their cultural, educational and people-to-people exchanges.

But the relationship between the two is not without conflicts.

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, this year has been marked by increased tensions between Beijing and Jakarta over the South China Sea.

Chinese ships have been found trespassing in Indonesian territory near the South China Sea several times, where the two countries have different legal bases.

Over the year, Indonesia has regularly repelled Chinese coast guard vessels and fishing boats from an area to which Beijing says it has a historic claim.

Another issue is a growth in anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia. This has existed since the mid-1960s, when suspected communists – some of them of Chinese descent – were killed after the military alleged they had instigated an attempted coup. Chinese-Indonesians were also blamed for Indonesia’s economic downturn during the Asian Financial Crisis because of their involvement in many of the country’s businesses.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which originated from Wuhan, China, has worsened this.

Many Indonesians on social media use the term “Chinese virus” to refer to COVID-19. Some have been calling for people to stay away from places where Chinese citizens or Chinese Indonesians work and live.

The entry of 500 workers from China amid the COVID-19 pandemic caused an uproar. People rejected these workers for fear they might not only bring the virus but also take over local people’s jobs.

Yet the continuous visits by both countries’ officials may indicate these tensions are nothing to worry about.

Luhut’s latest visit to discuss vaccines is only the latest of these diplomatic exchanges.

Before Luhut, Indonesia’s minister of foreign affairs, Retno Marsudi, along with the minister of state-owned enterprises, Erick Thohir, visited Hainan, China, in August to discuss progress on China’s massive infrastructure project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Luhut’s role

Former army general Luhut is the most prominent person enabling Jakarta’s growing ties with Beijing.

Not only does he hold a top ministerial position, he is also a powerful politician. Many believe that, de facto, he is the man who has the last say in the administration of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, securing him the title “Lord Luhut”.

Luhut has visited Beijing several times. During his visits, he has shown Indonesia’s commitment to the Belt and Road Initiative.

He even established and led the Global Maritime Fulcrum Task Force, which oversees the implementation of BRI projects in Indonesia by involving various ministries and stakeholders.

Luhut has defended Indonesia’s inclination towards China in public forums. He argued that resisting China would not benefit Indonesia as China controls about 18% of the global economy.

“So, you like it or not, happy or not happy, China is a world power that cannot be ignored,” he said.

On the South China Sea issue, Luhut asserted that it should not be escalated and instead blamed Indonesia’s limited capability and number of ships in the area.

Luhut’s statements show his influence in relation to China’s growing role in Indonesia.

The impacts

The growing ties between China and Indonesia could result in the former having strong footholds in the latter, either economically, politically or militarily.

This could make Indonesia highly dependent on China. It could also damage Jakarta’s ties with the US.

Indonesia recently rejected a US proposal to allow its P-8 Poseidon maritime surveillance planes to land and refuel on Indonesian territory.

The proposal came as the US and China escalated their contest for influence in Southeast Asia. The P-8 plays a central role in keeping an eye on China’s military activity in the South China Sea.

Indonesia explained that this decision was part of the country’s neutral foreign policy, which does not take sides between the US or China.

However, Dino Patti Djalal, a former Indonesian ambassador to the US, begs to differ.

“We don’t want to be duped into [the US’] anti-China campaign [in the region]. Of course we maintain our independence, but there is deeper economic engagement and China is now the most impactful country in the world for Indonesia,” he said.

Habib Pashya, a Universitas Islam Indonesia student, contributed to this article.