As soon as the teaching term finished, I went into the bookshop to buy some holiday reading. I came away with three books: no tomes these. They were all graphic novels. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s classic, Watchmen was the first I scooped up, and then the recent published Sally Heathcote Suffragette and Jane, the Fox & Me.

As a professor of English literature, reading books on holiday can seem like a busman’s holiday. Teaching and researching books is my livelihood. But books are also my lifeblood, and fiction offers me an escape from the real world. Graphic novels provide the perfect holiday recipe to this conundrum: they’re distanced enough from my work for me to be able to enjoy them without having to think in my accustomed analytical way.

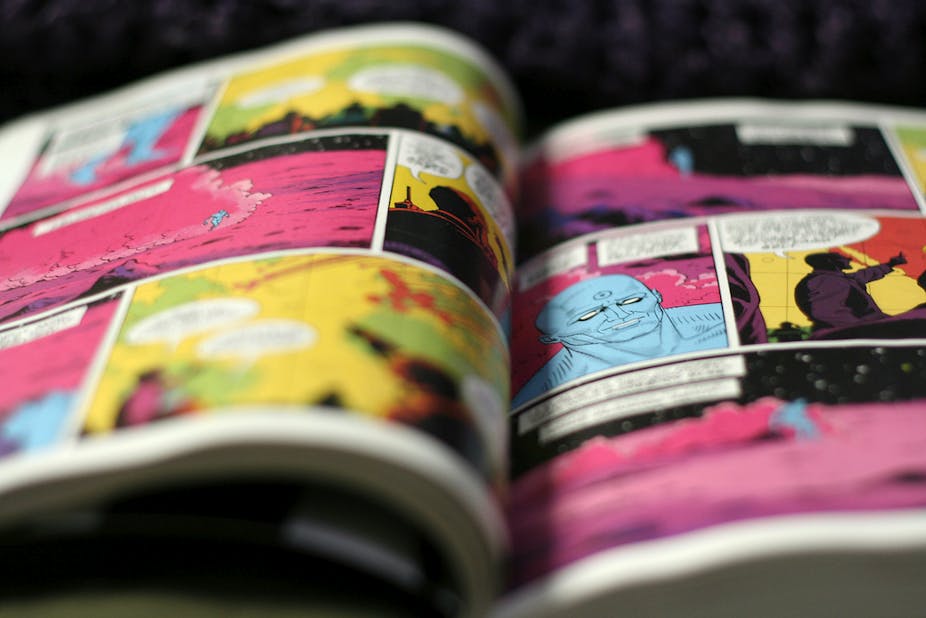

Graphic novels are similar to comic books, except they are published as single works, rather than in periodical form. As a genre they appeal to me because the narrative combination of visuals and captions takes me right back to the reading experience of my childhood and adolescence. And I love them for the innovative ways they address issues that are explored in conventional novels. They’re like a breath of fresh air after poring through words in my dusty study.

Mary and Bryan Talbot, the authors of Sally Heathcote Suffragette, have published a graphic novel before: Dotter of her Father’s Eyes. It combines autobiography and biography – at once an exploration of Mary Talbot’s childhood and relationship with her father, interwoven with an account of James Joyce’s daughter Lucia. Dotter of her Father’s Eyes won the Costa biography prize in 2012, indicating just how mainstream graphic novels have become.

Dotter of her Father’s Eyes is influenced by the work of the cartoonist Alison Bechdel, whose own graphic memoir about her father, first introduced me to graphic fiction in 2006. And Bechdel has recently published a companion memoir, which draws heavily on psychoanalysis, to explore her relationship with her mother.

In fact, graphic novels seems particularly well suited to exploring issues relating to the mind and to mental health. This is because they are able to represent the inner life and the external “reality” simultaneously. Sarah Leavitt’s compelling Tangles, for example, traces the impact of Alzheimer’s Disease on Leavitt’s mother and on her family.

So it’s not all about pretty pictures. The form allows some weighty topics to be tackled in an open and accessible way, which is refreshing. Sally Heathcote Suffragette is a different kind of graphic novel. It’s not a memoir, but an example of historical fiction. It tells the story of a young orphaned domestic servant who went on to become a campaigner for women’s suffrage in the first decades of the 20th century. The Suffragettes whose lives have been recounted most often are those from the upper and upper-middle classes, so here we have an example of history from below, a different and quite new perspective.

But one of the huge attractions of graphic fiction is the visual art. Sally Heathcote Suffragette doesn’t have a fantasy sci-fi element, but the detailed illustrations of Edwardian England and the apocalyptic representation of events are reminiscent of steampunk. In the middle of the book the politicians who opposed women’s suffrage are depicted as vicious cats rather than men. This deliberately recalls Art Spiegleman’s portrayal of Nazi soldiers in his famous Maus, a book which explores the impact of the Holocaust on Spiegleman’s family.

Sally Heathcote Suffragette didn’t make it into my suitcase. I read it immediately. But I’m not sure that Jane, the Fox & Me and Watchmen will either – the large format of graphic novels doesn’t lend itself to packing. I guess I’ll just have to read them both now …

Guilty Pleasures is a summer series in which academics reveal their most embarrassing cultural inclinations. Over the next few weeks, you’ll find out what literature professors delve into on holiday, when they can’t quite bear to crack into that next classic.