If battle reenactments are your thing, today will be of particular significance – at least if you’re in the UK.

Britain has for some months now been building up towards the anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo. Some 200 years ago today, on June 18 1815, Napoleon Bonaparte fought his last battle on a plain of rolling hills about 18 kilometres south of Brussels.

He was defeated, but only just, by a multi-national force of English, Irish, Scottish, Belgian, Dutch, Prussian and German troops (from Nassau, Hannover and Brunswick) commanded by the Duke of Wellington. Napoleon fled the field and was later sent into exile on St Helena, where he was to die six years later. After the battle, Wellington famously remarked that it was “the nearest run thing you ever saw”.

The British have pulled out all stops to mark the occasion. There are exhibitions, events, and conferences all over the country designed to celebrate and remember the battle. The most spectacular of those celebrations is a massive re-enactment on the very site of Waterloo involving more than 5,000 re-enactors, including 300 horses and 100 canon.

People have gathered from all over the world to perform a number of “scenarios” over three days, which the organisers expect will attract around 60,000 onlookers. The official website of Waterloo 200 urges spectators to “Come and participate from the very front line”.

The show, it promises, will be “fun for all, and full of emotions”.

Surprisingly, it appears the British public needs reminding what Waterloo was all about. It might have been the end game of a struggle that cost millions of lives, and that lasted more than 20 years, but a survey carried out this year by the National Army Museum in the UK showed that many of the respondents were more likely to associate Waterloo with the London railway station or the ABBA song than the actual battle.

Worse, of those between the ages of 18 and 24 who replied to the survey, one in eight said that they had never heard of Waterloo. When asked who commanded the British forces, almost half of those polled replied Sir Francis Drake, Winston Churchill, King Arthur or even Dumbledore.

More than a quarter (28%) had no idea who won the battle, while one in seven (14%) believed that the French had won.

So the battle, it would seem, really only appeals to military buffs, to obscure academics such as myself who write about the era, and to that strange subset of amateur historians called the battle re-enactor.

On any given weekend, in many countries in the world, thousands of people come together to play at war, from Roman times to Viking battles, from the English Civil War through to the first world war, the second world war, the Korean War, and even the Vietnam War. But these re-enactments pale in comparison to the American Civil War.

In 1998, as many as 25,000 “troops” took part in the recreation of the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, possibly the largest re-enactment in history to date. Next month, the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 will be played out.

If you want to see a mass of medieval arrows launched across a field, a siege engine at work, how 16-foot pikes were used during the English Civil war, an 18th-century musket or cannon being fired, or what an American tank looks like, then re-enactments can do all of that.

I visited a re-enactment of Waterloo in 2008 while researching a biography of Napoleon. It was the first time I had seen the site of the battlefield (admittedly greatly altered over the last two hundred years) and heard and smelt musket and cannon fire. There were only a dozen or so cannon but the ground beneath my feet nevertheless trembled.

Imagine then what it must have been like when hundreds of cannon went off at the same time. And this is where the re-enactment both fires the imagination but also fails to re-produce accurately the conditions of battle. The figures are very rubbery, but we think that about 200,000 men fought at Waterloo over an area of four square kilometres that was constantly pounded by 412 canon.

By the end of the day, anywhere between 42,000 and 53,000 were killed and wounded, along with 10,000 horses.

The mutilation and disintegration of bodies, both human and animal, caused by the impact of iron canonballs or roundshot weighing between six (2.7 kilos) and twelve pounds (5.4 kilos) could be devastating.

But this was not the only form of violence. It was as much psychological as physical. What might be termed the intimate horror of battle is redolent in the memoirs of the day. Alexander Mercer, a gunner with the British army, recalled the first man that fell among their ranks. It was an accident.

Gunner Butterworth had both his arms blown off below the elbow as he stumbled and fell before a canon just as it went off. He later bled to death. Other “moments” can be found throughout this and other memoirs: a gunner whose head had been blown off by a canon shot, except the face, which still remained attached to the neck, its eyes open; the body of a French soldier, sitting up against the wheel of a broken gun-carriage, whose right hand was frozen in a raised position; a horse that had both its hind legs blown away, and which just sat on its tail throughout the night after the battle, unable to move; or the raging thirst that afflicted men who were desperate enough to try to quench it by drinking from ditches in which there were dead bodies that had turned the fetid water red with blood.

After the battle, local peasants, not to mention the survivors, roamed the field taking whatever they considered of any value – shoes and stockings were the most valuable items of clothing – sometimes killing the wounded in order to do so, or cutting off fingers or ears to get at jewellery.

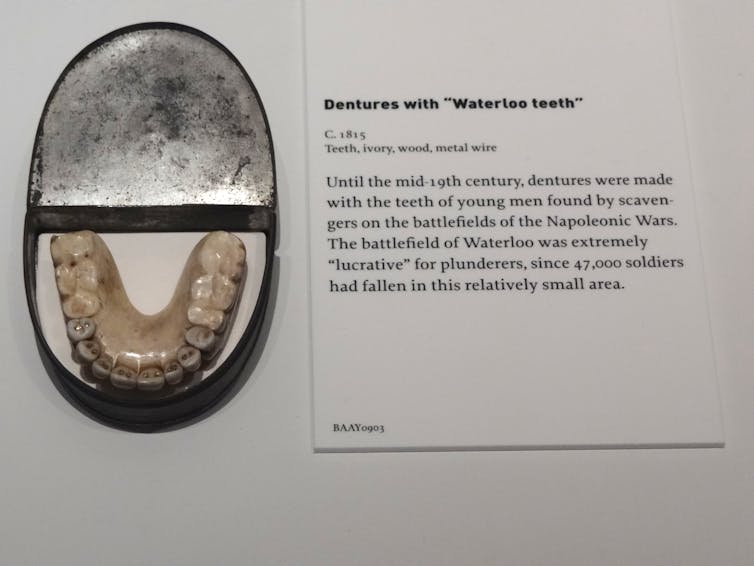

It is said that by 9 o’clock on the morning after the battle (the sun rose a little before 4 o’clock) the peasantry had stripped all of the dead naked. Some camp followers specialised in extracting teeth from the dead, which they then on sold to London dentists, where they were set in ivory.

Rather than conceal their source, dentists advertised their dentures as “Waterloo teeth” or “Waterloo ivory”. It was a guarantee that they came from young, healthy soldiers, killed in the prime of life, rather then from rotting corpses dug up by grave robbers, or executed criminals.

Fifty years after the battle, dental catalogues still advertised “Waterloo teeth”, although fresh supplies came from the battlefields of the American Civil War.

What is it exactly then that the thousands of men and women running around a site that had once been soaked in blood are celebrating? The motives of the re-enactors can, of course, vary enormously.

Some might be paying homage to relatives that once fought, others are trying to recreate the past, others again just like getting dressed up and reliving the fantasies of their childhood.

But it is worth reminding ourselves that war is not a game and that Waterloo was one of the bloodiest battles in history … until the first world war came along.