Before vaccines were developed, infectious diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus and meningitis were the leading cause of death and illness in the world. Vaccines are one of the greatest public health achievements in history, having drastically reduced deaths and illness from infectious causes.

There is a large gap between vaccination rates for funded vaccines for adults in Australia and those for infants. More than 93% of infants are vaccinated in Australia, while in adults the rates are between 53-75%. Much more needs to be done to prevent infections in adults, particularly those at risk.

If you are an adult in Australia, the kinds of vaccines you need to get will depend on several factors, including whether you missed out on childhood vaccines, if you are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, your occupation, how old you are and whether you intend to go travelling.

For those born in Australia

Children up to four years and aged 10-15 receive vaccines under the National Immunisation Schedule. These are for hepatitis B, whooping cough, diphtheria, tetanus, measles, mumps, rubella, polio, haemophilus influenzae B, rotavirus, pneumococcal and meningococcal disease, chickenpox and the human papillomavirus (HPV).

Immunity following vaccination varies depending on the vaccine. For example, the measles vaccine protects for a long duration, possibly a lifetime, whereas immunity wanes for pertussis (whooping cough). Boosters are given for many vaccines to improve immunity.

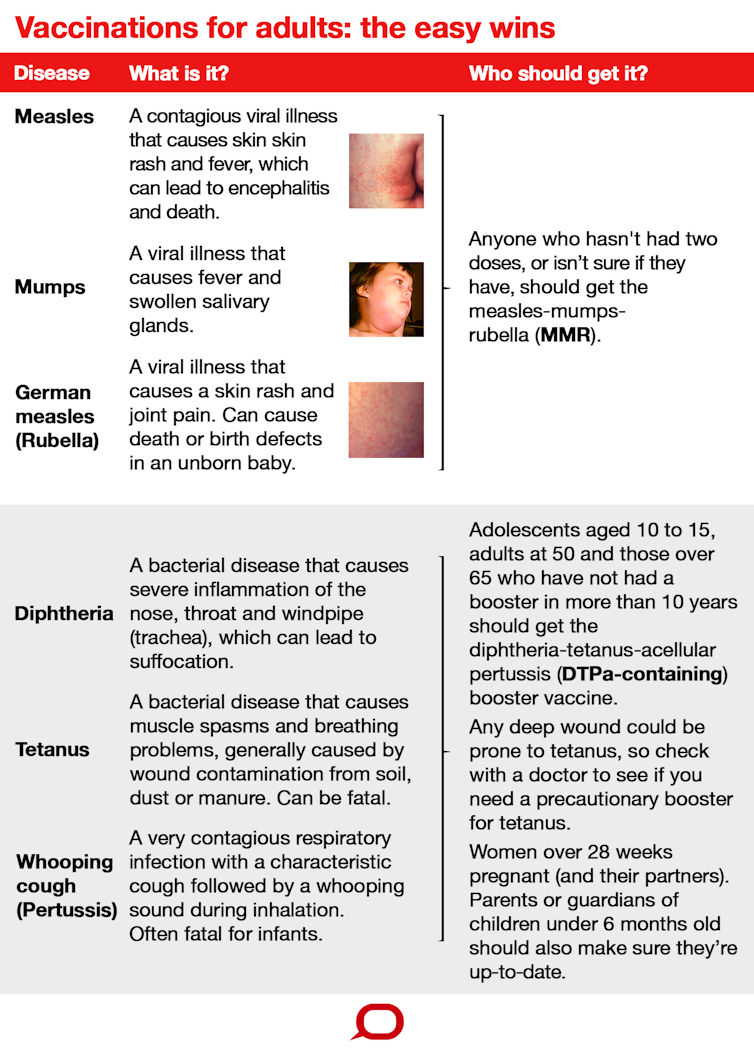

Measles, mumps, rubella, chickenpox, diphtheria and tetanus

People born in Australia before 1966 likely have natural immunity to measles as the viruses were circulating widely prior to the vaccination program. People born after 1965 should have received two doses of a measles vaccine. Those who haven’t, or aren’t sure, can safely receive a vaccine to avoid infection and prevent transmission to babies too young to be vaccinated.

Measles vaccine can be given as MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) or MMRV, which includes varicella (chickenpox). The varicella vaccine on its own (not combined in MMRV) is advised for people aged 14 and over who have not had chickenpox, especially women of childbearing age.

Booster doses of diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough vaccines, are available free at age 10-15, and recommended at 50 years old and also at 65 years and over if not received in the previous ten years. Anyone unsure of their tetanus vaccination status who sustains a tetanus-prone wound (generally a deep puncture or wound) should get vaccinated. While tetanus is rare in Australia, most cases we see are in older adults.

Whooping cough

Pregnant women are recommended to get the diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine in the third trimester to protect the vulnerable infant after it is born, and influenza vaccine at any stage of the pregnancy (see below under influenza).

Pertussis (whooping cough) is a contagious respiratory infection dangerous for babies. One in every 200 babies who contract whooping cough will die.

It is particularly important for women from 28 weeks gestation to ensure they are vaccinated, as well as the partners of these women and anyone else who is taking care of a child younger than six months old. Deaths from pertussis are also documented in elderly Australians.

Read more: 'No Vax, No Visit'? If mum was vaccinated baby is already protected against whooping cough

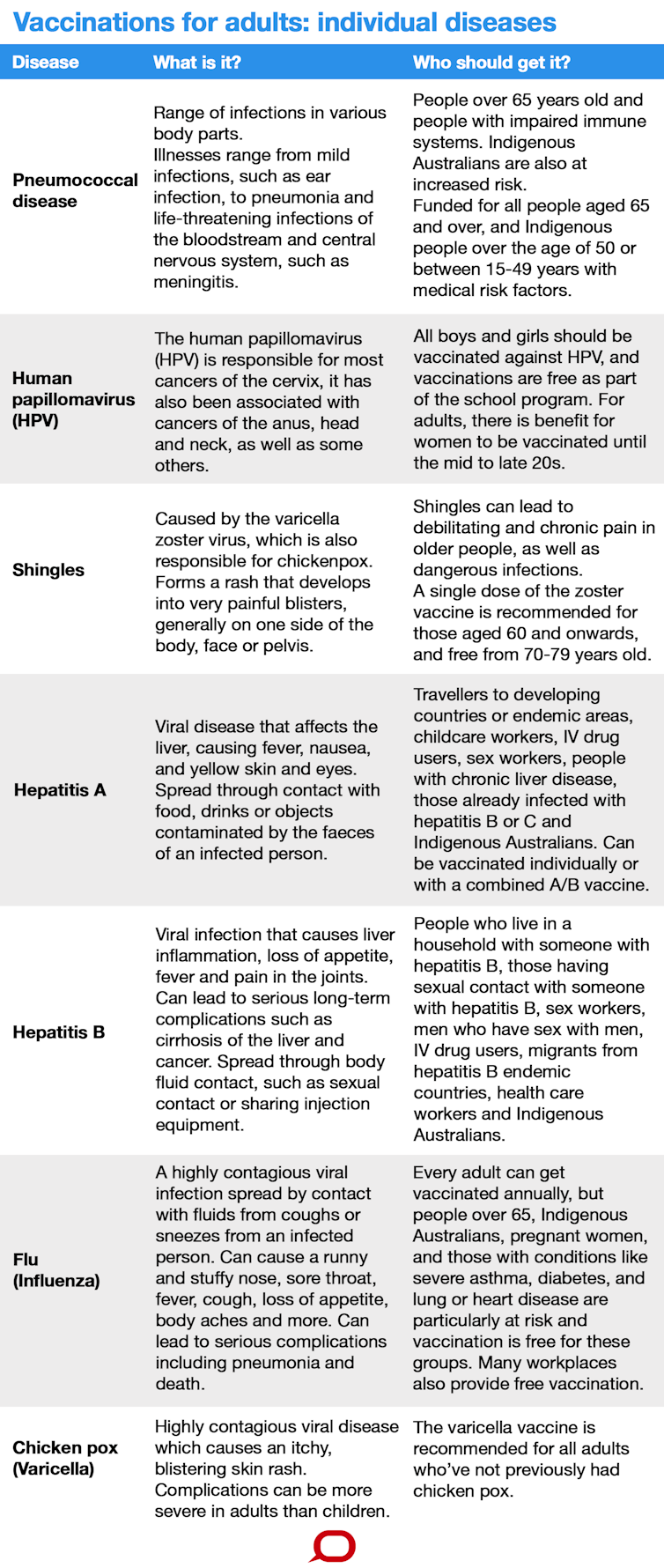

Pneumococcal disease and influenza

The pneumococcal vaccine is funded for everyone aged 65 and over, and recommended for anyone under 65 with risk factors such as chronic lung disease.

Anyone from the age of six months can get the flu (influenza) vaccine. The vaccine can be given to any adult who requests it, but is only funded if they fall into defined risk groups such as pregnant women, Indigenous Australians, peopled aged 65 and over, or those with a medical condition such as chronic lung, cardiac or kidney disease.

Flu vaccine is matched every year to the anticipated circulating flu viruses and is quite effective. The vaccine covers four strains of influenza. Pregnant women are at increased risk of the flu and recommended for influenza vaccine any time during pregnancy.

Read more: Millions of Australian adults are unvaccinated and it's increasing disease risk for all of us

Health workers, childcare workers and aged-care workers are a priority for vaccination because they care for sick or vulnerable people in institutions at risk of outbreaks. Influenza is the most important vaccine for these occupational groups, and some organisations provide free staff vaccinations. Otherwise, you can ask your doctor for a vaccination.

Any person whose immune system is weakened through medication or illness (such as HIV) is at increased risk of infections. However, live viral or bacterial vaccines must not be given to immunosuppressed people. They must seek medical advice on which vaccines can be safely given.

Hepatitis

Australian-born children receive four shots of the hepatitis B vaccine, but some adults are advised to get vaccinations for hepatitis A or B. Those recommended to receive the hepatitis A vaccine are: travellers to hepatitis A endemic areas; people whose jobs put them at risk of acquiring hepatitis A including childcare workers and plumbers; men who have sex with men; injecting drug users; people with developmental disabilities; those with chronic liver disease, liver organ transplant recipients or those chronically infected with hepatitis B or hepatitis C.

Those recommended to get the hepatitis B vaccine are: people who live in a household with someone infected with hepatitis B; those having sexual contact with someone infected with hepatitis B; sex workers; men who have sex with men; injecting drug users; migrants from hepatitis B endemic countries; healthcare workers; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders; and some others at high risk at their workplace or due to a medical condition.

Read more: Explainer: the A, B, C, D and E of hepatitis

Human papillomavirus

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine protects against cervical, anal, head and neck cancers, as well as some others. It is available for boys and girls and delivered in high school, usually in year seven. There is benefit for older girls and women to be vaccinated, at least up to their mid-to-late 20s.

The elderly

With ageing comes a progressive decline in the immune system and a corresponding increase in risk of infections. Vaccination is the low-hanging fruit for healthy ageing. The elderly are advised to receive the influenza, pneumococcal and shingles vaccines.

Influenza and pneumonia are major preventable causes of illness and death in older people. The flu causes deaths in children and the elderly during severe seasons.

The most common cause of pneumonia is streptococcus pneumonia, which can be prevented with the pneumococcal vaccine. There are two types of pneumococcal vaccines: pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV). Both protect against invasive pneumococcal disease (such as meningitis and the blood infection referred to as septicemia), and the conjugate vaccine is proven to reduce the risk of pneumonia.

The government funds influenza (annually) and pneumococcal vaccines for people aged 65 and over.

Shingles is a reactivation of the chickenpox virus. It causes a high burden of disease in older people (who have had chickenpox before) and can lead to debilitating and chronic pain. The shingles vaccine is recommended for people aged 60 and over. The government funds it for people aged 70 to 79.

Read more: Explainer: how do you get shingles and who should be vaccinated against it?

Australian travellers

Travel is a major vector for transmission of infections around the world, and travellers are at high risk of preventable infections. Most epidemics of measles, for example, are imported through travel. People may be under-vaccinated for measles if they missed a dose in childhood.

Anyone travelling should discuss vaccines with their doctor. If unsure of measles vaccination status, vaccination is recommended. This will depend on where people are travelling, and may include vaccination for yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, cholera, typhoid, hepatitis A or influenza.

Travellers who are visiting friends and relatives overseas often fail to take precautions such as vaccination and do not perceive themselves as being at risk. In fact, they are at higher risk of preventable infections because they may be staying in traditional communities rather than hotels, and can be exposed to risks such as contaminated water, food or mosquitoes.

Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders

Indigenous Australians are at increased risk of infections and have access to funded vaccines against influenza (anyone over six months old) and pneumococcal disease (for infants, everyone over 50 years and those aged 15-49 with chronic diseases).

They are also advised to get hepatitis B vaccine if they haven’t already received it. Unfortunately, overall vaccine coverage for these groups is low – between 13% and 50%, representing a real lost opportunity.

Read more: Dr G. Yunupingu's legacy: it's time to get rid of chronic hepatitis B in Indigenous Australia

Migrants and refugees

Migrants and refugees are at risk of vaccine-preventable infections because they may be under-vaccinated and come from countries with a high incidence of infection. There is no systematic means for GPs to identify people at risk of under-vaccination, but the new Australian Immunisation Register will help if GPs can check the immunisation status of their patients.

The funding of catch-up vaccination has also been a major obstacle until now. In July 2017 the government announced free catch-up vaccinations for children aged 10-19 and for all newly arrived refugees. This covers any childhood vaccine on the National Immunisation Schedule that has been missed.

While this does not cover all under-vaccinated refugees, it is a welcome development. If you are not newly arrived but a migrant or refugee, check with your doctor about catch-up vaccination.