Our gut does more than help us digest food; the bacteria that call our intestines home have been implicated in everything from our mental health and sleep, to weight gain and cravings for certain foods. This series examines how far the science has come and whether there’s anything we can do to improve the health of our gut.

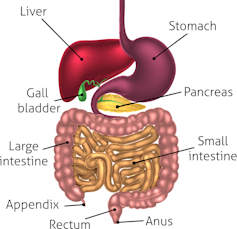

The healthy human body is swarming with microorganisms. They inhabit every nook and cranny on the surfaces of our body. But by far the largest collection of microorganisms reside in our gastrointestinal tract – our gut.

These tiny organisms, which can only be seen with the aid of a microscope, make up our microbiota. The combination of microbiota, the products it makes, and the environment it lives within, is called the microbiome.

Great advances in DNA sequencing technologies have enabled us to study the gut microbiota in intricate detail. We can now take a census of all the microorganisms that are in the microbiota to help us understand what they are doing.

Typically, our gut microbiota consists of several thousand different types of bacteria, as well as other microbes such as viruses and yeasts. Some types will be in abundance, while other types will be rare.

The exact composition of each person’s microbiota is as unique as their finger prints. But unlike finger prints, the microbiota is constantly changing.

Microbes start to colonise our gut and skin the moment we are born. The mode of birth, either natural or by caesarean, determines the sort of microbes a baby first contacts. This can have a profound effect on the early development of the microbial populations that contribute to the microbiota.

The structure of the microbiota – that is, what microbes are present and the relative numbers of each type – undergoes significant change from its establishment at birth until it matures in early adolescence.

In healthy adults, changes over time are likely to be small. But major shifts in composition can occur when we radically change our diet or take antibiotics, which are, of course, designed to kill bacteria.

It’s also been found that, like our own body, the composition of our microbiota changes in old age, including a loss of diversity.

Our microbiota is not an accidental, free-loading passenger living in our gut and stealing the nutrients from our food. Over the millennia we have evolved with our microbiota. We now know it can affect many aspects of our biology, from our digestive system to our brain function.

How our bodies develop and function is dictated by our genes. We have approximately 20,000 genes encoded in our genetic material.

The different microbes that make up our microbiota have their own genes. As a rough estimate, the 2,000 different types of microbes may, on average, each carry 3,000 genes. That means the microbiota carries six million genes. Although many will have similar functions, it still indicates the microbiota has a much more complex =genetic complement= than we ourselves have.

This genetic complement of the microbiota means it can do things other parts of the body cannot. Our microbiota provides digestive enzymes to allow us to use food that otherwise we could not digest. It provides essential vitamins we cannot make ourselves. And it interacts with our hormonal and neural systems to help shape our physiology.

Perhaps most important of all, it helps to develop our immune system to fight off bugs. The body must be able to distinguish between the beneficial members of the healthy microbiota and invading pathogenic microorganisms that can cause disease. The immune system has to learn to live with and nurture the microbiota while fighting off pathogens.

Disruption of the correct interaction between microbiota and the immune system may be one of the causes of the massive increase over the past few decades in immune-related diseases, such as diabetes, food allergies, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Many of these diseases seem to be diseases of affluence, probably influenced by poor diets and excessive cleanliness, affecting the early establishment of an appropriate microbiota.

The intimate connection between host and microbiota and the rich contribution that each brings to the partnership has resulted in the concept of a metaorganism. This recognises that as humans, we are really the product of the mutual cooperation between our own bodies and our microbiota.

Indeed, our microbiota is so important and has such specific functions that it’s reasonable to view it as another organ of our body. It’s just as important as our liver or kidneys.

Read the other articles in our Gut series here.