TESTING ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES - La Trobe University’s decision to accept funding from Swisse for a new centre to research alternative medicines has sparked controversy. This series looks at how the evidence behind alternative medicines can be assessed, and the ethics of such links between industry and research institutions.

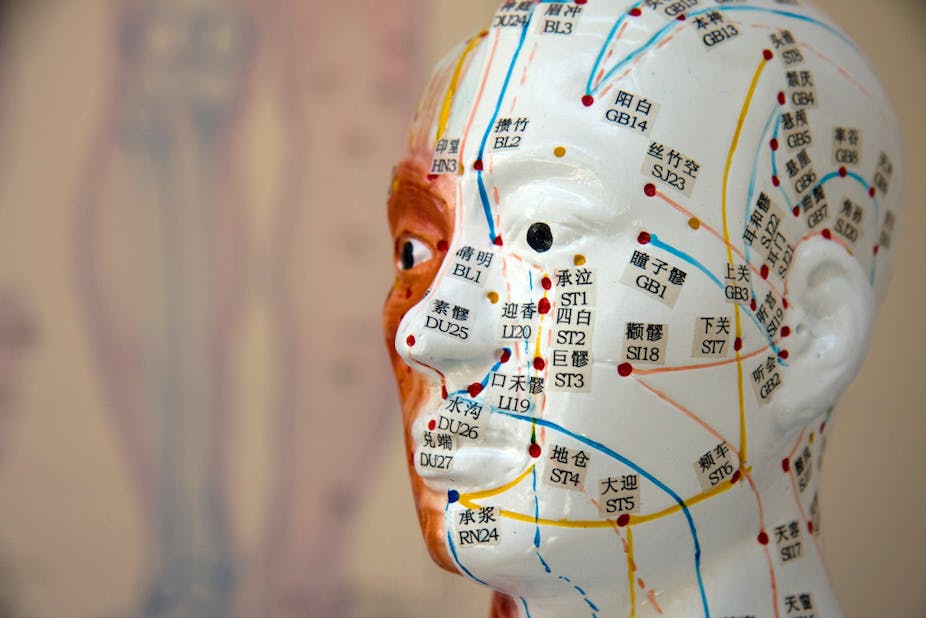

Acupuncture, chiropractic, herbal medicines, massage, and other therapies known collectively as complementary and alternative medicine, are big business in Australia, as elsewhere.

About two-thirds of Australians use such products and practices over the course of a year. Nonetheless, the debate around these therapies remains dominated by emotive and political commentary – on both sides.

Doing the right kind of research

Like all other areas of health-care practice and consumption, complementary therapies need to be underwritten by rigorous scientific investigation. The gold standard of such work is the randomised controlled trial, which aims to establish whether a treatment or medicine is clinically efficacious.

This type of research is to be applauded and encouraged. But the current popularity of alternative therapies highlights the immediate need for parallel public health and health-services research.

What we need is a broad range and mix of methods and approaches that are essential to understanding the place and use of complementary therapies within contemporary health care.

Such an approach provides findings of direct benefit to practice and policy. It would be in the interest of patients, practitioners, and those managing and directing health policy to address critical questions such as why, when, and how alternative therapies are currently consumed and practiced.

Studies along these lines help provide a factual platform for ensuring safe, effective health care. And it’s important to note that such investigations are neither for complementary medicine nor against it.

Rather, the work is undertaken in the spirit of critical and rigorous empirical study that charts a path free from the emotion we have become accustomed to on this topic.

A burgeoning body of work

A number of recent Australian projects have started to do just this kind of research, to explore the use and practice of alternative therapies from a critical public health and health-services research perspective.

Research drawing on a large, nationally representative sample of 1,835 pregnant women, for instance, has shown that complementary therapies are popular for pregnancy-related conditions. The researchers found nearly half (49.4%) of the women they studied had consulted an alternative-therapy practitioner at the same time as a maternity-care provider for a pregnancy-related condition.

Similarly, another study found 40% of Australian women with back pain who were surveyed had consulted a complementary-therapy practitioner, as well as a health provider for back pain.

Other Australian research has found that women in rural areas are statistically more likely to use alternative medicine than their counterparts in urban Australia.

And use has been identified as high among older Australian men and women as well as among people with depression, cancer, and a range of chronic conditions.

In these and other areas of health-seeking behaviour and utilisation, the core issues requiring further examination include how people make the decision to use complementary therapies, and how they seek information and engage with them.

Uncovering use

The use of alternative therapies is often a hidden activity within the community and, in many cases, distanced from both formal care and health-care providers (and, in some cases, divorced from complementary therapists as well). This raises a number of potential risks around safety, efficiency, and coordination of care.

While many people condemn complementary and alternative therapies because of a lack of clinical evidence, this doesn’t constitute a scientific platform for ignoring or denying research on the subject.

In fact, it’s the opposite case. If we accept that most complementary therapies have at best emerging, weak, or no clinical evidence, then it surely becomes necessary to try and more fully understand what drives people to use them, in what manner and setting they use them, and what information they draw upon to decide whether they’ll use them.

At a time when health-care funding is stretched by our ageing population and rise of chronic illnesses, it’s imperative that research-based assessments of future practice, policy and financial planning include consideration of all health treatments.

Such research will not only help produce a critical, non-partisan platform for better understanding complementary and alternative therapies, it will also provide a rigorous and broad evidence-base with which to help people, practitioners, and policymakers on this significant component of Australians’ health care.

This is the first article in our series about complementary and alternative therapies. Click on the links below to read the others:

Can we scientifically test herbal medicines?